Marcus Sedgwick's festive short story - part 1: When the sun stands still

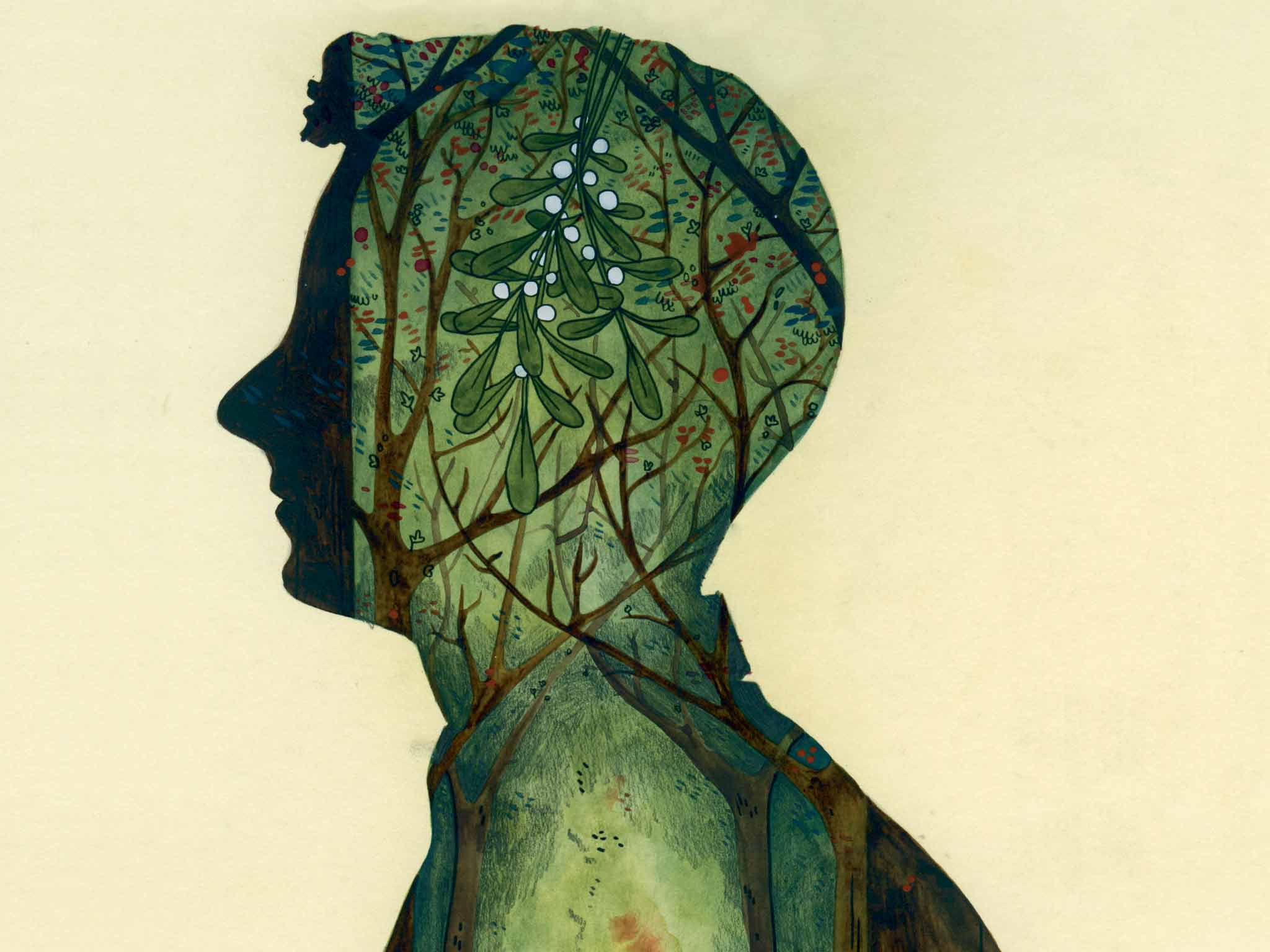

He saw a figure in a green cloak collecting mistletoe from a colossal oak

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was, from the very beginning, impossible.

Since October, Gawain had been struggling to do what the features editor had demanded of him and produce a "spooky story" for the Christmas Eve issue of the newspaper. Somehow, word had spread that when not sub-editing for the sports pages, he dabbled with fiction. Unfortunately, the features editor had discovered this, a matter he usually tried to keep hidden. He only had himself to blame; he knew the source of the leak: Gwen, the new girl on the features desk. He'd supposed she might be impressed, and one evening in the lift he blurted out something about "tinkering with his book". She giggled; he spent the remainder of the longest ride in elevator history dying.

"Original, yes?" the editor had said. He had an awful way of sounding both enthusiastic and intimidating at the same time. He was also one of the most unread men who had ever disgraced the inside of a newsroom, more concerned with nursing the precious features section Twitter feed than actually commissioning articles.

Once, on his birthday, the features desk had clubbed together to buy him a thesaurus. He didn't see the joke, nor did he ever take the wrapper off the book. It was a mystery as to how he had come up with the idea of running a short story in the paper, but that is what seemed to fixate him. Worse, he had no idea that, when it came to ghost stories, there simply was no such thing as original, despite Gawain's attempts to tell him so.

"Won't have it," said his editor, who had the habit of speaking in incomplete sentences, as if perpetually squeezing his thoughts into 140 characters. "Smart young man. Piece of cake..."

The weeks rolled by, and with every abortive idea that wandered into his head, Gawain only felt the truth being hammered into him: every story had been written, and if he was honest, that was what was stopping that book of his from ever happening. What was the damn point in writing fiction anyway? Someone had done it before you. Someone had always done it before you. And better.

Even if he did finish it, what then? He was tired of correcting the spelling mistakes in "exclusives" about non-existent transfers of Premier League footballers. He was tired of the colour of the carpet under his desk. Though he did not yet realise it, Gawain was tired of life.

One Tuesday morning in December, with the editor getting rather snarky about the ghost story, Gawain snapped.

"Actually," he said, with as much sarcasm as he had the nerve to muster, "I do have one idea..."

"Namely?"

"Well, there's this grumpy old git who hates Christmas, total miser, utterly tight-fisted."

"Yes?"

"Yes, well, on Christmas Eve he's visited by a ghost, the ghost of his business partner. And he sends three more spirits: one from the past, one from the present, and one from the future, who all show him what a bastard he's been. And it changes him totally."

The editor stood, his eyes blinking rapidly, during which time Gawain was already mentally putting on his coat and clearing out his desk into a bin liner.

"Excellent," stated the editor. "Bloody brilliant. That or nothing!" k

So Gawain was left with the task of rewriting the most famous Christmas story of all time in such a way that no one else in the entire world would notice.

On the Sunday before Christmas, he still had nothing.

Monday morning came and he shuffled through the city. Four days to Christmas. The story to be delivered tomorrow and the office party tonight, where no doubt he would be treated to the sight of Gwen being chatted up by the editor, edging her backwards inch by inch towards the mistletoe.

Christmas. Bloody Christmas. All around, people scurried by, hurrying to the demands of their lives. Yet the streets had looked this way since the end of October, when the lights had gone up, and displays had sprung into view in every shop, despite the fact that everyone Gawain knew detested that it all happened so early. There was no one who didn't moan about the commercialism, the months of build-up.

The weather didn't help: today was another grey, drizzly day. The only snow to be seen was on Christmas cards and boxes of biscuits in M&S. Not even a hint of a frost. And no sight of the sun, though above the grey clouds the sun was there, Gawain supposed, yet he had no idea that it was slowing down. Slowing down, to a stop.

Above all, Gawain hated Christmas so much because, despite all the nonsense, the expectation, the commercialism, the cheap crap piled high inside every shop, the laughable adverts for something called perfume the rest of the year yet now mysteriously called parfum, despite it all, Christmas still had some inconceivable power over him. Just as it had over everyone else. Was it the lingering memory of being a child, when the thing still had genuine magic? Whatever it was, he resented being torn in two like this; loathing it and yearning for it.

He turned into the square where the offices were. All as it had been for months; save for one thing. That old man.

It was odd, in a city of teeming millions, with shoppers and tourists coming and going, how in a small corner such as this, you could get to know every face, a village within the city; and though you might not know anyone's name, an unfamiliar figure was not hard to spot.

Since Thursday last week, that old man had been standing outside the newsagents, hanging around doing nothing. Gawain assumed he was old; he wore a filthy green anorak with the hood pulled up, and little more could be seen of him than a dirty grey beard. And every day Gawain had walked past him, and the old man had wished him a happy new year.

It wasn't even Christmas yet.

The first time, Gawain had said, "Sorry, I don't have any spare change," which wasn't true. The second time, he'd said the same thing, and it had been.

Now Gawain passed the old man again, and once more, he bade him a happy new year.

"A little early for that, isn't it?" Gawain asked, putting his hand in his pocket. He knew there was a two-pound coin in there somewhere. He held out the money, but the man didn't take it. Instead, he just nodded and said, "It's later than you think." Feeling unaccountably odd, Gawain slunk off to the office.

The day came and went. At lunch he tried to write a few lines of the story, but by now he knew he'd failed and would have to admit to his failure. There would be trouble, of significant proportions. Failure to deliver four pages of the paper on deadline... He may as well go down to HR now and ask for his P45.

Since four, people had been drifting off to the Christmas party. Commercial were long gone, while in editorial, bottles of beer and wine had materialised since lunch. Gawain had accepted a couple of drinks, thinking that a little lubrication couldn't hurt. Sadly it hadn't helped either, and he had still written nothing when one of his colleagues loomed over his shoulder.

"Finished?"

Gawain nodded his head, sombrely.

"I am."

Drinking continued in their usual venue, a pizzeria around the corner from the office, after which they decamped to The Nutshell. There, Gwen ended up in the corner by the fruit machine with the editor, while Gawain looked sadly on, wondering how you chat someone up with tweets. Gwen giggled. Gawain's heart curled into a ball and wished it were dead, and Gawain tried to oblige by drowning it in red wine.

Finally, approaching midnight, he staggered away, looking for a night bus.

There was the old man again. Despite the state Gawain was in, or perhaps because of it, something about the old man arrested him. He seemed to be still, when everything else around him was fizzing. Brash, electric and noisy.

"Happy New Year," he said again.

Gawain stood stock-still and looked at him hard, properly, for the first time. But it was dark and Gawain was drunk and he could see little past the beard.

"Why do you keep saying that?"

"Because the new year starts tomorrow."

"I'm pretty sure you're wrong about that," said Gawain, who didn't feel sure of anything just then. "I think Christmas has to come first, then New Year."

"Not according to the sun," said the old man. "In five hours' time, the sun will stop in the sky. Then it will start to move once more, and grow."

Gawain blinked, swaying on his feet slightly. k

"Would you like to see something?" asked the man.

"Sure," mumbled Gawain, "why not?"

The man held out an arm towards an alleyway. Gawain peered at it. There was nothing so remarkable about the alleyway other than the fact that Gawain had never seen it before, despite working in this square for six years.

It did not occur to him that under normal circumstances he would never accompany a stranger into a dark alley in the middle of the night. Instead, he simply shrugged and followed the man.

It was suddenly very quiet. The strident fizzing of the world from moments before seemed to fall away. No cars, no sirens, no drunken shouts, no footfall.

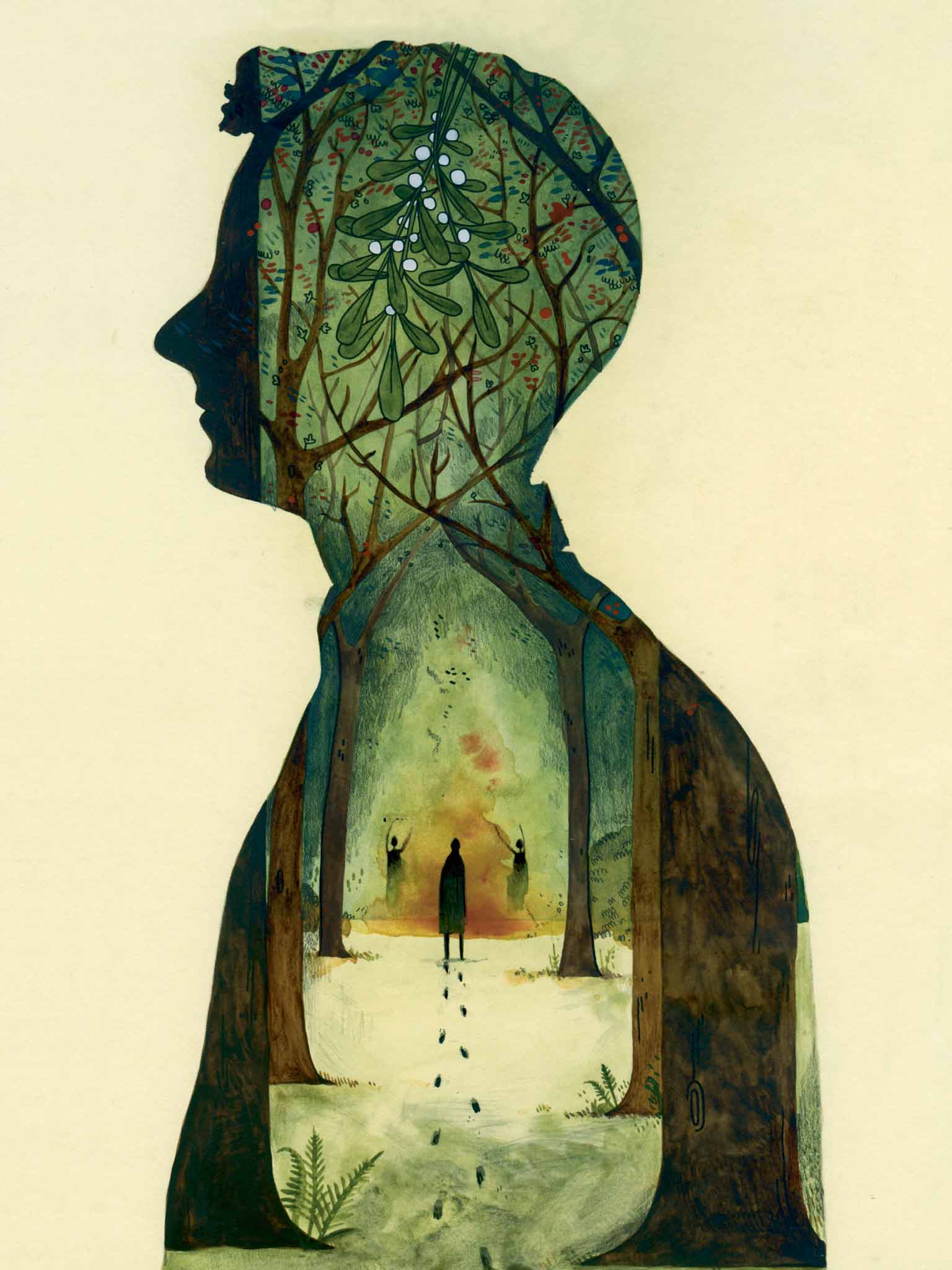

Ahead of him, through the mist of his vision, he saw a tree; a rare enough sight in the city. Then he saw more trees, lots more. Tall trees, old ones. Powerful ones.

He walked on. Even in his drunken state, he was now aware he was standing in a forest, an ancient forest. There was thick snow underfoot. His breath came out in venting bouts of steam.

The man lifted his arm once more.

"Look," he said. "This is what happens when the sun stands still."

Gawain looked. He saw people. He saw old things. He saw fires being lit, and people leaping across the flames. There was wine and ale; there were feasts. There were prayers of beginning, of increase, of light. Now he saw a figure in a green cloak, wielding a long-handled scythe, collecting mistletoe from the branches of a colossal oak, and he became aware that there was singing. Somewhere, someone was singing a song to the sun, which arose and slanted through the trees, lancing its way through the mistletoe. It gleamed. The old man turned to Gawain, a sprig of it in his hand.

"Here," he said, "is the Golden Bough."

He held it out.

But that was not what Gawain was looking at; he was looking at the face of the old man, which he could see properly for the first time. He was looking into the future, for the man looking back at him with a mixture of amusement and pity on his face, was, quite undeniably, his older self.

Part 2 of this story is published next week

© Marcus Sedgwick

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments