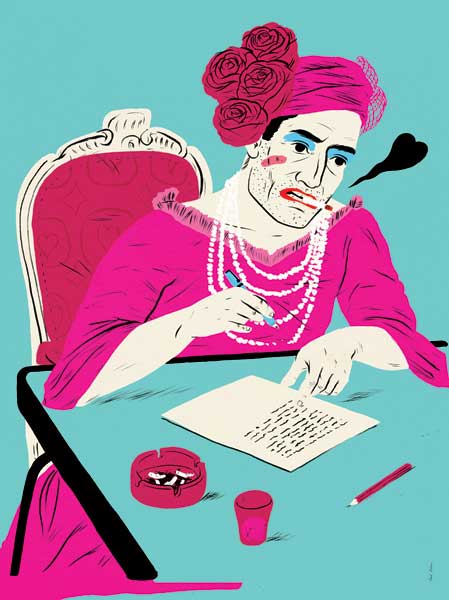

Love changes everything: The men picking up Barbara Cartland's baton

Barbara Cartland's stranglehold over the nation's heartstrings is being challenged by a curious breed: this Valentine's Day, the romantic novel in your hands might have been written – try not to blush, now – by a man

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mention romantic fiction and, within a sentence, the chiffon-clad ghost of Barbara Cartland appears as predictably as the handsome heroes or damsels in distress who haunt her books. The self-styled "Queen of Romance" may have been dead for a decade but – thanks to her 723 titles, billion-plus sales, and passionate public advocacy of more mystery and less mechanics where the course of true love was concerned – she continues to cast a shadow over the genre that she came to personify.

"When I was starting out in the 1970s, they tried to market me as the new Barbara Cartland," recalls Penny Jordan, whose sales now total 85 million, making her a pretender to Cartland's throne. It didn't work out, she reports, with no discernible disappointment. There was only one Barbara Cartland. Instead, Jordan concentrated on establishing her own style. If the crown remains unclaimed, she suggests, it may be for a positive reason – namely that it is redundant. "Romantic fiction has changed such a lot, even in the years I have been doing it. We are finally getting rid of the reputation for churning out penny-dreadfuls."

Typical of a new generation of writers in the genre is India Grey. In her early thirties and a graduate in English from Manchester University, she recently won the Romantic Novelists' Association (RNA) Romance Prize for Mistress: Hired for the Billionaire's Pleasure. She has never, she admits, read a Cartland. "I came to romantic fiction when I was 10 and on holiday in France and picked up my stepmother's Jilly Cooper. It is Jilly's type of funny, fresh, naughty romantic fiction that inspired me. There's nothing old-ladyish about it and no whiff of Devon violets."

Definitions vary as to quite what constitutes romantic fiction. Is it Cartland's chaste courtships or Grey's raunchier romps? Is it restricted to the 102-year-old Mills & Boon imprint and its upstart rival, Little Black Dress Books (part of the Headline group), or does it stretch to include all sorts of saga, adventure and historical? One distinguishing characteristic, though, is accepted by all: it is something written by women for women. The only men admitted are imaginary ones with one too many shirt buttons undone.

Or are they? "As far as I am aware," reports the author Hugh Rae, who prefers a polo neck in his publicity shots, "there are just four male members of the Romantic Novelists' Association." Rae brings a certain expertise to bear on the subject because he is one of that quartet, all of whom publish under female pseudonyms – Rae as Jessica Stirling, Bill Spence as Jessica Blair, Roger Sanderson as Gill Sanderson and Ian Blair as Emma Blair.

Rae has, in his own words, spent the past 32 years "hiding under the skirts" of his female alter ego, authoring family sagas and historical novels set in Scotland. "It was only when I was up for an award 10 years ago, and might have had to go on stage to receive it, that I finally came out," he recalls, "though I'm sure most of the people who read the books still don't have a clue." Why the deception? Surely, in 2010, readers are enlightened enough to accept that men can be romantic too. "As a genre," Rae reflects, "we're still aimed squarely at women, from having central female characters right down to the design of the cover. So having a woman's name on there is judged essential. And there is a perception that doesn't go away that guys are not that good at writing about emotional relationships. Having said all that, when it was revealed that I was Jessica Stirling, it had no impact at all on my sales."

Spence has had a rather different experience. A former RAF pilot, he didn't turn to the genre until 1992, by which time he had a long back catalogue – in his own name – of war and cowboy novels. When he submitted his first historical romance, The Red Shawl, to publishers Piatkus, it was as Bill Spence. But they insisted on a female pen name, which is how he ended up as Jessica Blair. "You don't say no to publishers," says Spence. "They never told me the reasons behind their choice."

Yet the real identity of Jessica Blair has never been kept a secret. Quite the opposite. "My publishers were going to keep quiet at first," Spence remembers, "but changed their mind almost at once. In the publicity for The Red Shawl they made great play of the author being a man writing as a woman." Mills & Boon has done the same with Roger Sanderson, who writes as Gill Sanderson but is tantalisingly billed as the only man on the publisher's list of authors.

Next month, Spence publishes his 16th Blair novel, Sealed Secrets, set, like the previous 15, on the Yorkshire coast around Whitby. Isn't he tempted to use his real name now and be done with the whole charade? "I'm not sure it would work from a marketing point of view," he replies. It is an astute answer for, in romantic fiction arguably more than other genre, marketing is all. Mills & Boon, for instance, not only has a set of guidelines for what aspiring writers should and shouldn't include in the unsolicited manuscripts still submitted in their thousands; it also has a rigid template for how published works are to be presented. It is a formula that places the publishing brand and the recognisable signs of the genre above the promotion of individual authors.

"There is definitely a homogeneous house style," concedes Grey, "and the name of the author is kept small. What they want to ensure, unlike in other genres, is a steady supply of new books for an audience that will buy as many as are available, and won't become over-attached to any single writer."

Even individual writers have more than one identity. As Annie Groves (her mother's maiden name), Penny Jordan has a series of Second World War sagas about the Campion family; as Caroline Courtney, she wrote Regency romances; as Melinda Wright, "air-hostess novels" (this before the advent of budget airlines dispelled the traditional notion that pushing a trolley up a plane's aisle was glamorous); and as Lydia Hitchcock, romantic thrillers. So, given that identity is something to be assumed and cast off at will, would she ever think of writing as a man? Jordan laughs. "If my readers saw a man's name on the spine, it would put them off. And me too. I'd wonder if he could write romantic fiction, if he could really convince a readership that is almost entirely female."

Even the otherwise very modern Grey shares the same doubts. "Increasingly, our readers are not little old ladies who borrow our books from libraries. They are young, professional women, who are aspirational, well-qualified and intelligent. But romantic fiction remains a woman thing. It is best written by women in a code that women understand, about feelings that women have."

So, no men admitted? "Well," she concedes, "a lot of men do write romantic fiction, but they aren't marketed that way. If you take Atonement by Ian McEwan or Sebastian Faulks's novels – books about relationships that feature strong female characters – what else are they if not romantic fiction? But if you called Ian McEwan romantic fiction, he would no doubt feel put down or patronised."

What about Hugh Rae and Bill Spence? Do they still feel outsiders in Grey's "women's club"? "I dispute this idea that men are different from women," counters Spence. "I am romantic and I am sentimental and I am a man. It's all down to perception." Rae is more nuanced. "I always say that I write for women, not as a woman," he insists. But he is unconvinced that the dearth of male writers in the world of romantic fiction will change any time soon. "The four of us guys, to be honest, are all knocking on a bit," he points out, "and I've seen no sign of anyone else male coming up behind us, pseudonym or not."

The extract

Sealed Secrets, By Jessica Blair (Piatkus £19.99)

'... Don't deceive me any more, Robert Dane, Addison or whatever other name you so easily use ... I lived a life of hope that a future with you would be filled with happiness; I foresaw that one day you would share your secrets with me but you have admitted you never would. You made me deceive myself. That's not the sort of love I want! ... Go to her, Robert, go to the girl you really love!'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments