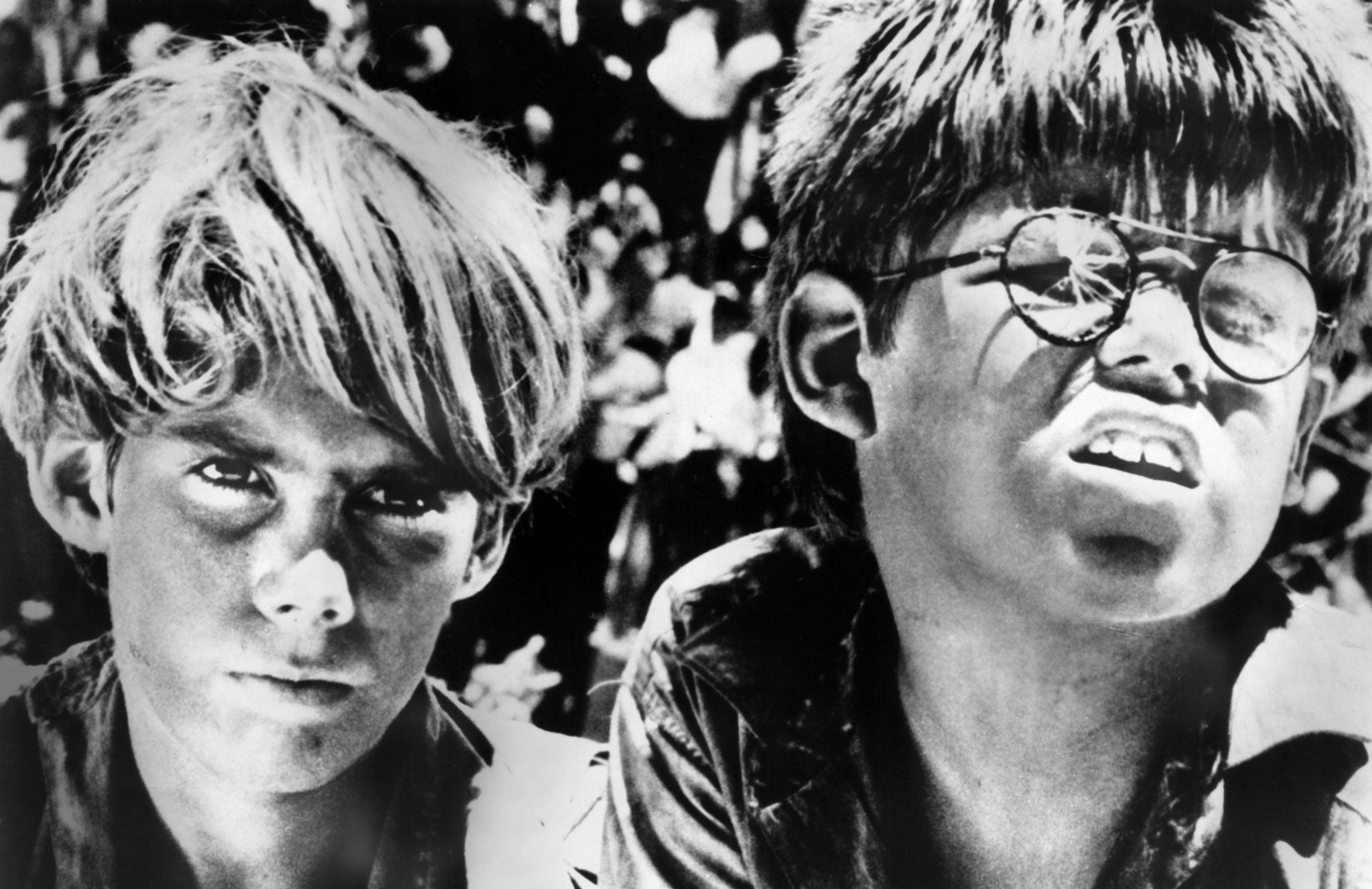

Lord of the Flies is still a blueprint for savagery

Six decades ago, William Golding set out a terrifying view of the base instincts of a marooned band of children. But how close to the truth was ‘Lord of the Flies’? Eleanor Learmonth and Jenny Tabakoff leaf through a dark and bloody history of disaster

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."I'm afraid. Of us."

Those words first appeared in print exactly 60 years ago when William Golding published his most famous novel, Lord of the Flies.

It's easy to see how Golding got the inspiration for his tale of humanity red in tooth and claw: he had served in the Royal Navy during the Second World War and wrote Lord of the Flies while teaching boys at Bishop Wordsworth's School.

For our book No Mercy, we spent five years researching how accurately Golding's novel reflects the behaviour of real-life groups of disaster survivors stranded in isolated corners of the globe, asking: did Golding get it right?

It turns out he did.

Accounts of survivor groups through history – from the siege of Numantia in 134BC to the Chilean miners trapped under the Atacama desert in 2010 – mirror what happened on Golding's imaginary tropical island. When Ralph tells Piggy he's afraid "of us", reality shows he was right to be afraid. The destructive processes Golding described are astonishingly accurate.

When groups of people are clinging to life, the greatest threat may be not the harsh environment, starvation or dehydration, but the other survivors standing next to them on the deserted beach or the remote, snow-covered mountain.

Group fragmentation, leadership struggles, personal hatred, theft, abuse, frenzied violence, the discarding of empathy and compassion – these are all things that afflicted both Golding's schoolboys and many real survivor groups.

The real-life 'Lord of the Flies'

The Robbers Cave Experiment

A group of boys find themselves stranded in a beautiful but isolated environment. For a brief period things go well, but then human nature starts to assert itself, and their mini-society descends swiftly into antagonism, hostility and violence. That was the fascinating premise of not one, but two books published in 1954.

But while Lord of the Flies was a novel, Muzafer Sherif's The Robbers Cave Experiment was factual: a scholarly text that also became highly influential, although much less famous.

The spark that lit Golding's creative fuse was his scorn for the books he had been reading to his children, particularly RM Ballantyne's The Coral Island. As a teacher, Golding found Ballantyne's depiction of boys living in an island utopia of fun and friendship deeply unconvincing.

While Golding worked his way through rejections and rewrites, an experiment was taking place in Oklahoma that would start with a very similar premise. Twenty-two boys were let loose in a deserted scout camp in the Robbers Cave State Park by a team of psychologists headed by Muzafer and Carolyn Sherif. The boys were given food, shelter and almost-complete autonomy, with the researchers there only to observe them. The aim of the experiment was to generate friction between two groups of strangers, then bring them together to resolve their differences by forcing them to co-operate. The participants, who thought they were attending a normal summer camp, were 11-year-old boys.

Sherif and his team carefully selected intelligent, well-adjusted boys from middle-class, white families. The researchers pretended to be camp staff and janitors, and melted into the background. The boys were divided into two groups before arriving: later called the "Rattlers" and the "Eagles".

In phase one of the experiment, each group was left alone for a week of camping, hiking and swimming. Both established their own hierarchies, unaware of the other group's existence.

Then Sherif allowed them to hear the other group in the distance, which sparked immediate signs of rivalry and territorialism in both groups. The announcement by the staff of a tournament between the two tribes caused even greater hostility: as soon as they set eyes on each other, the insults started to fly. After losing an early contest, the Eagles dispensed with their complacent leader; a more aggressive boy seized power and immediately threatened to beat up anyone on his own team who didn't take the competition seriously. The first day ended with the Eagles seizing and burning the Rattlers' flag; the next day, the Rattlers destroyed the Eagles' flag. Brawls erupted and the researchers had to break them up.

Later, the Rattlers executed a night raid on the Eagles camp, wearing full war paint to terrify the enemy. They raced into the cabin unopposed, smashing and stealing. The Eagles leader rounded on his routed troops, accusing them of being "yellow", and they subsequently carried out a counterattack on the Rattlers camp armed with sticks and baseball bats.

Mission accomplished, they retreated and rearmed, this time filling socks with stones.

The psychologists watched the arms race escalate over the following days. Finally, one violent mob brawl became so sustained that the researchers were forced to step in, drag the boys apart and remove them to separate locations.

How long did it take for mere friction to escalate into a juvenile war, in an idyllic setting where everyone had plenty of food? Phase two lasted just six days from the first insult ("Fatty!") to the final all-out brawl. Golding would have loved it.

The fear of the supernatural

The 'Belgica' and the trapped Chilean miners

Golding was also right about the corrosive effects of darkness, fear and the spectre of the supernatural. The Lord of the Flies boys, stranded by a plane crash on an uninhabited island paradise, are paralysed by their fear of an unseen creature they call "the beast".

Most of the boys are convinced the beast will emerge under the cover of darkness to kill them. Their fear is so intense that they resort to ritual sacrifices of flesh to appease the beast.

Golding saw belief in the beast as a tipping point in the boys' journey from civilisation to base, human instinct: "The world, that understandable and lawful world, was slipping away."

Civilisation has a habit of slipping away from stranded and stressed survivors as irrational fears start to surface. Trapped in the Antarctic ice on the Belgica in 1898, ship's doctor Frederick Cook observed the effects on the crew of the "soul-despairing darkness" of the polar winter. Although they had adequate supplies, the men's physical and mental state deteriorated rapidly as they were incapacitated by depression and fear.

When one man, Emile Danco, died three weeks into the polar night, Cook was convinced the darkness had hastened the death. Unable to bury Danco, the men hacked a hole through the thick sea-ice next to the Belgica, and dropped the weighted body in.

Soon the men were being plagued by mysterious groaning sounds that reverberated through the hull of the ship. Many were convinced it was Danco, and had visions of his corpse suspended directly beneath their ship. Even the ship's cat, Nansen, went mad and died. Another crewman developed symptoms identical to Danco and became gravely ill and deranged. Luckily, they were saved by the return of spring and the release of the Belgica from the pack-ice.

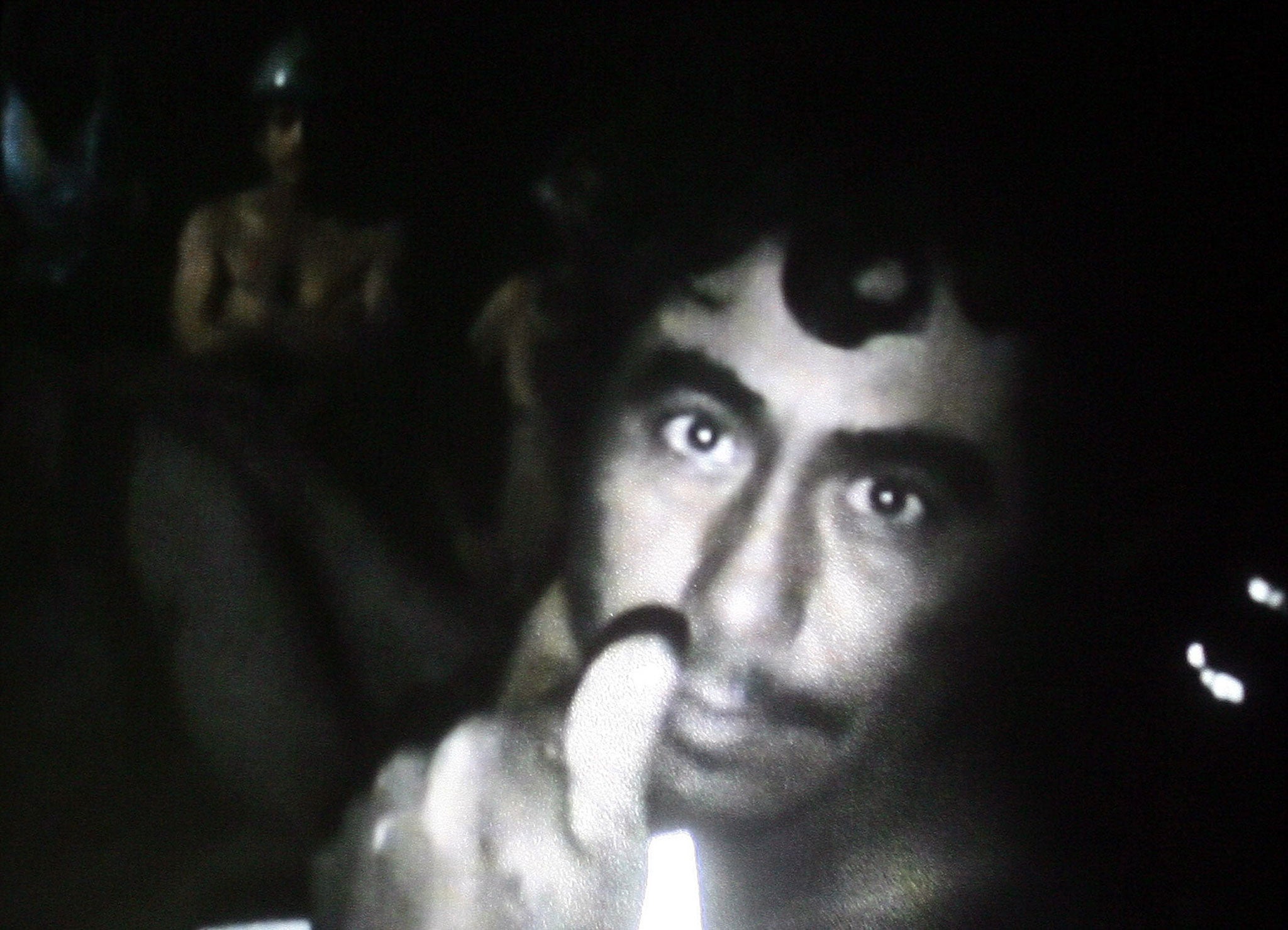

As recently as 2010, the Chilean miners trapped in the collapsed San José mine reported many sightings of small apparitions flitting through the black corners of the mine. They were so common the men gave them a name – "mineros chicos". Several men also felt evil manifesting out of the rock itself. "The Devil was there – we weren't alone," said Samuel Avalos. "I felt that evil presence myself."

In a 1959 BBC radio interview, Golding reflected on the appearance of the beast and its meaning: "It's the things that have crawled out of their own bones and their own veins, they don't know whether it's a beast from the sky, air, or where it's coming, but there is something terrible about it as the conditions of existence."

The darkness

The raft of the 'Medusa'

During the day, survivor groups have to contend with hunger, thirst, in-fighting and other pragmatic issues. But as night comes, a new issue emerges: the darkness itself.

For the 147 survivors of the wrecked Medusa abandoned by their longboat-sailing shipmates on a huge, unseaworthy raft in 1816, the darkness stirred up a potent mix of terror, despair and mindless aggression. On their second night adrift off the West African coast, a collective insanity descended and a pitched battle began on the raft. "The soldiers and sailors," wrote one of the few survivors later, "terrified by the presence of inevitable danger, gave themselves up for lost."

An orgy of destruction ensued, directed both at the raft, which they tried to chop up, and other passengers. People were hacked or beaten to death and thrown into the sea. Unarmed, deranged men used their teeth and fists: one man had his ankle badly mauled, another nearly had his eyes gouged out. By morning, more than 60 were dead, but "as soon as daylight beamed upon us, we were all much more calm".

The survivors passed the day in a state of shock. There were now sharks circling, attracted by the blood and mutilated corpses caught in the structure of the raft.

Those who had survived managed to get through the next 24 hours unscathed, but on the fourth night, "darkness brought with it a renewal of our disorder in our weakened state. We observed in ourselves that natural terror… greatly increased in the silence of the night."

Some of the men became filled with a "horrid rage" and the slaughter recommenced. By the next morning, when the insanity had retreated, only 30 of the 147 who had boarded the raft were still alive.

Survivor maths

The 'Mignonette'

Often in dysfunctional survivor groups, a division quickly appears between the healthy and strong, and the weak and sick. Survivor maths reasoning works like this: if there is a set number of people consuming limited provisions, and it is likely that some will die in a few days anyway, why should the group waste precious food or water on the dying? Sometimes this means abandoning them, but at other times the calculation is much more ruthless.

Such was the situation aboard the dinghy of the Mignonette, in the infamous case of its cabin boy, Richard Parker. The Mignonette was sailing from England to Sydney in 1884, when the flimsy yacht suddenly sank after being hit by a large wave. Richard Parker found himself on a dinghy with three other men, floating more than 1,000km from the nearest land. After two weeks adrift, the captain, Tom Dudley, raised the issue of drawing lots and eating the loser. At first, the others refused, saying they should all die together. But the captain tried desperately to persuade them: "So let it be, but it is hard for four to die, when perhaps one might save the rest."

After several more days, Parker became (according to the others) sick and possibly comatose, at which point he became the loser of survivor maths. He is said to have muttered, "What, me?" as Dudley drove a penknife into his jugular. In his legal depositions, Dudley would initially claim Parker was unconscious, but somewhat later in his eight different versions of the truth, he admitted that Parker had spoken.

Singling out the sick and weak is useful to a survivor group in two ways. First, it can provide a seemingly legitimate rationale for abandonment or murder. Second, sick and weak people are much easier to dump or dispatch.

The Lord of the Flies principle is ruthless: if the strong are battling to survive, why should they waste care and resources on the weak? After all, one man dead would mean more food and water for the rest. In William Golding's novel, the first to die was a "littlun".

'No Mercy: True Stories of Disaster, Survival and Brutality' by Eleanor Learmonth and Jenny Tabakoff, will be published by Text on 27 March, priced £12.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments