Laurie Lee's Rosie: What is it like to inspire a writer's work and be immortalised forever on the page?

The inspiration for Laurie Lee's Rosie, who died this week, was relaxed about her literary alter ego. But not all writers' subjects have carried the burden so well, says Philip Womack

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

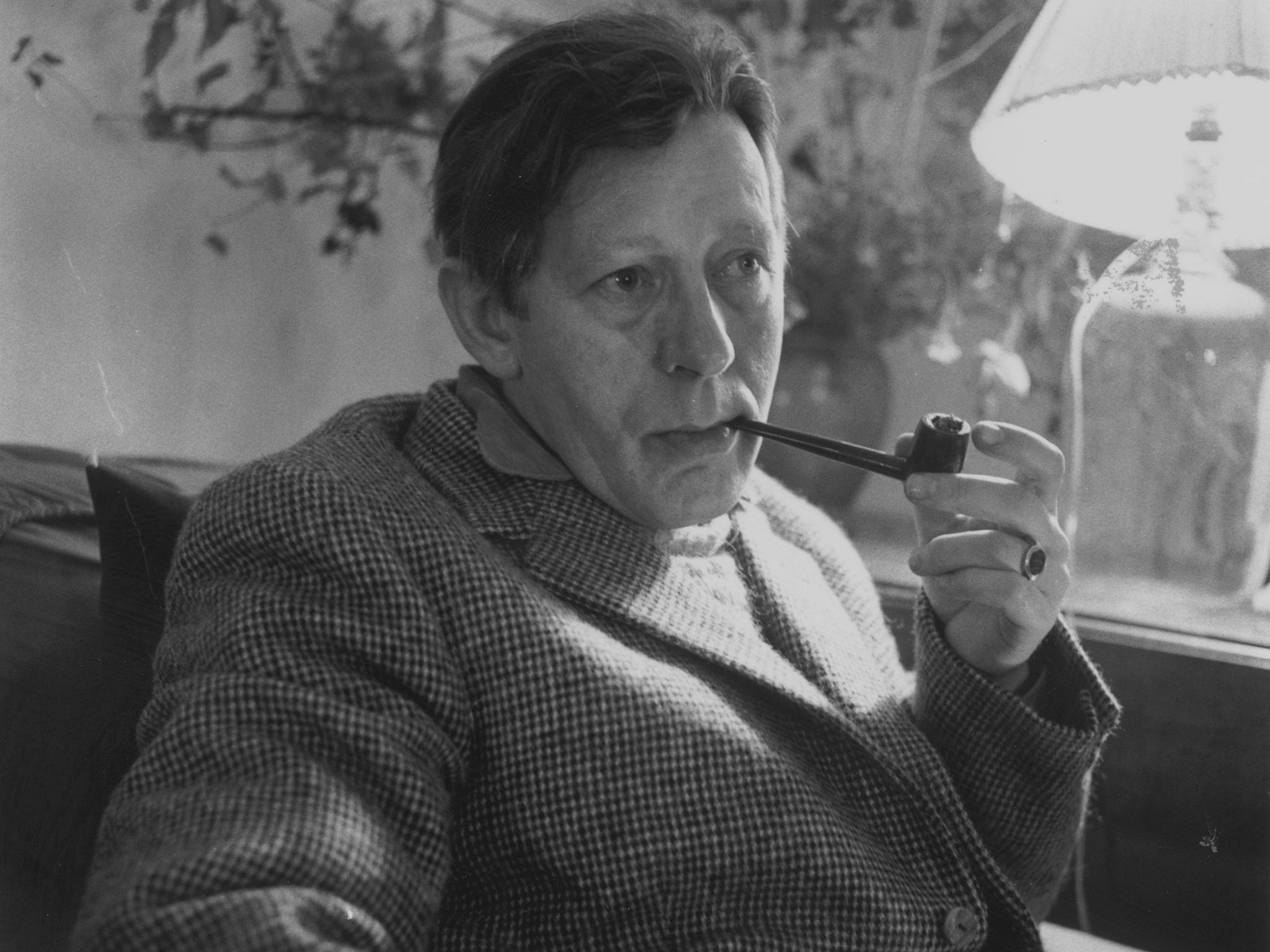

Your support makes all the difference.This week, Rosalind Buckland, a woman of almost 100 years old, died. She often told stories about her rural past to her family. It was a past that was, in fact, well-known to millions of readers, as she was a cousin of Laurie Lee, and the "Rosie" of his best-selling, sweetly evocative memoir, Cider with Rosie.

For 25 years after its publication in 1959, the identity of the cider-swigging girl who shared an encounter with a teenage Lee under a haycart remained a mystery, but as the only Rosie in the village of Slad at that time, Buckland wasn't hard to track down. She didn't talk very much about her role as inspirator. In fact, she always claimed never to have drunk the titular tipple – although when her granddaughter gave her a glass of champagne for her 90th birthday, she admitted that it tasted like cider.

Buckland seems to have had a much happier relationship with her cousin, and with her literary alter ego, than most people who've inspired great and popular works. She escaped seemingly unscathed from the more pernicious forces that can harry those whose real lives become tangled up with the imaginary ones that writers endow them with. While we see the creation, we rarely see the original; and the original can become obscured by the creation.

It is no wonder that Rosalind rarely spoke about her literary avatar. A name is a private thing: the Rosie that she thought herself to be was not – cannot be – the Rosie of the memoir. Perhaps she hardly remembered that moment under the cart; perhaps it had more significance for Lee than it did for her; perhaps it never happened.

There is a magic to being in a book that stems from our ages-old reverence for the written word and its power to contain, encode and transmit human thoughts and passions. To place another person into that literary matrix, then, seems something akin to a magic spell: you are stuck, in that guise, for ever, as if a wizard had turned you into wax where you stood.

To be the inspiration for a work that reaches across the globe, and even the centuries, is a complicated thing. It is at once a gift and a curse: to be immortalised in unchangeable texts, and yet to barely have the right of reply. As a gift, all the power stems from the author, who shapes an image of the self that the muse may not recognise; and many have found it more burdensome than not.

Real-life muses have, of course, been the generational force for books of great power and beauty. The Divine Comedy would not be what it is without Dante's love, Beatrice Portinari, as his guiding spirit and passion, translated into transcendent literature.

Some people do respond well to the fame of their literary selves: Dr Joseph Bell, the deerstalker-wearing Edinburgh surgeon who partly inspired Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes, was by all accounts immensely pleased by the connection. And some even seek it: Palle Huld made a round-the-world trip at the age of 15 which was said to have inspired Hergé's Tintin; while Hergé claimed he'd never heard of the boy, Huld encouraged the idea.

We will never know how the muses of the past responded to their depictions. The Roman lyric poets wrote furiously, and unsparingly, about real people. Catullus covered many pages of papyrus with erotic, sensual lines to Lesbia – a code name for his mistress, the aristocratic Clodia.

At the beginning of his cycle of poetry he delights in her, and is jealous of her pet sparrow as it is allowed to sit in her lap; by the end of their affair, he is decrying her as a prostitute who gets people off in alleyways. I would give anything to hear Lesbia's reply: to have no record of the private thoughts of this woman of wit and fire is a great sadness.

A recent play, John Logan's Peter and Alice, explored the nuances of literary immortality. It documented the meeting, in a bookshop, between Alice Liddell and Peter Llewelyn Davies, who between them inspired Lewis Carroll's Alice, and J M Barrie's Peter Pan. Both had difficult relationships with their immortalisers when they were children and neither asked to be put in a book.

The ambiguities of such fame are highlighted: Peter remembers how controlling J M Barrie was, while Alice looks on the man who made her famous with fondness and consolation. "What child wants to be immortal?" asks Davies. "What child thinks he isn't?" replies Alice.

The psychological impact of seeing oneself through the eyes of another, and for that inevitably one-sided view to become world-renowned, is hugely affecting: A A Milne's son Christopher Robin deeply resented the way that his father had used his early life for his Winnie-the-Pooh books, and grew to hate them.

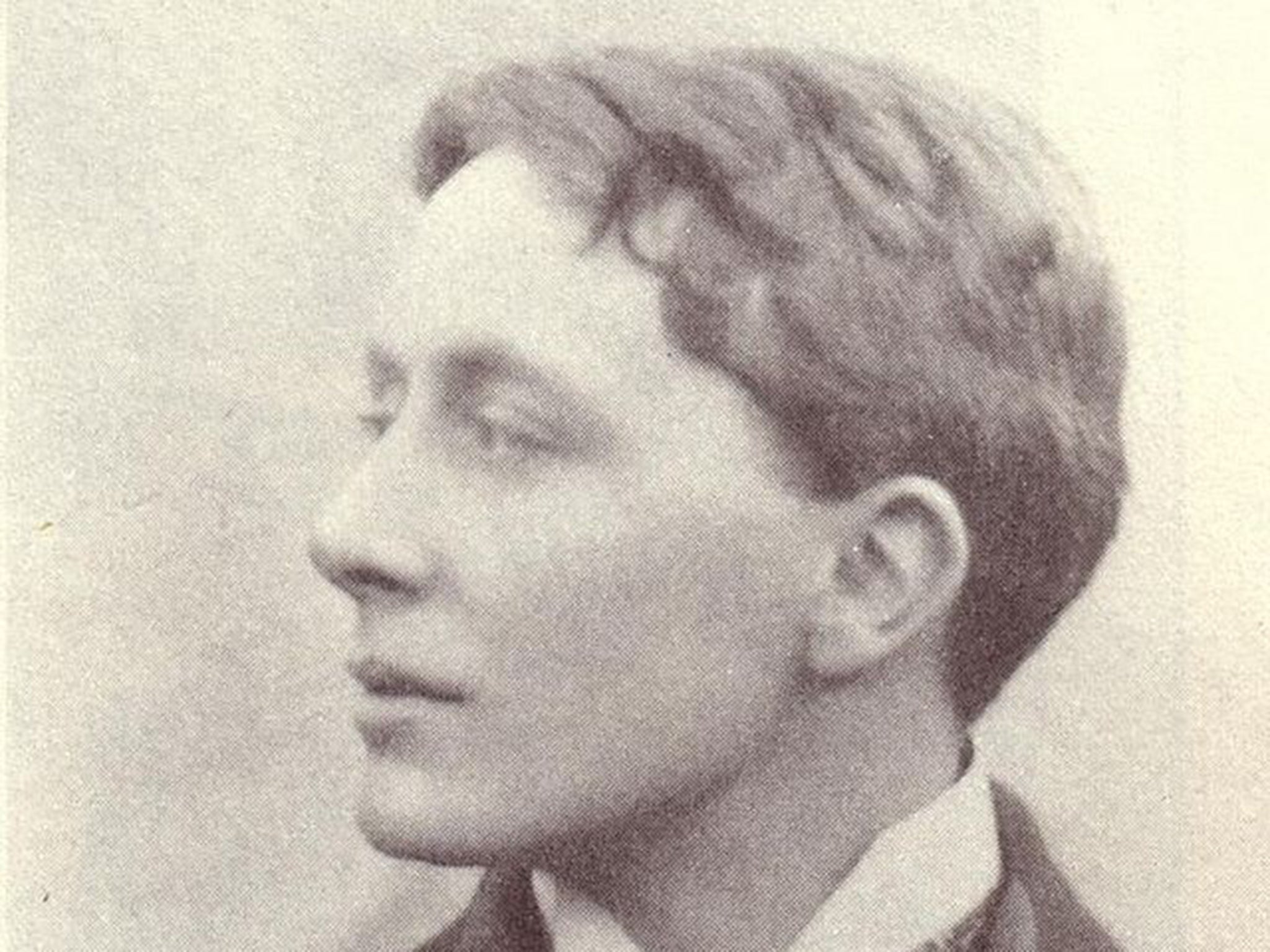

The handsome poet John Gray at first accepted, then denied the fact that he was the model for Oscar Wilde's beautiful aesthete, Dorian Gray, who stays young while his painting grows old. John Gray went on to become a priest; it is one of those strange ironies that while he is long dead, his literary alter ego, like Dorian's painting, lives on.

While muses remain largely powerless, there is a rare instance of one hitting back at her maker. F Scott Fitzgerald was completely unscrupulous in using material from his own life, with his damaged, beautiful wife Zelda as his constant inspiration. He even took work from her diaries and letters for his novels. When she did the same to him, for her 1932 book Save Me The Waltz, Fitzgerald was furious. It did neither of them any good, though, as their marriage, and their lives, were headed for disaster.

Maybe, somewhere among Rosalind Buckland's papers and diaries and letters, there is an account of what really happened under that haycart, from her point of view; and then we might see the writer through the muse's eye.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments