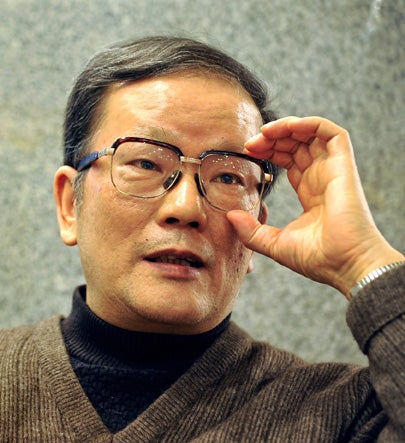

Jiang Rong: The hour of the wolf

The Chinese author has been jailed, denounced and barely escaped the death penalty. In Beijing, he tells Justin Hill why his epic novel has sold in its millions

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It is a moment famous in Chinese literature: a crowd of Chinese watch passively as a young patriot is led to his execution. Written by Lu Xun in the 1920s, this scene comes from A Call to Arms, a literary wake-up call to throw off the limitations of traditional culture. Perhaps as famous now, at least on university campuses across China, is a scene where a herd of sheep watch a Mongolian wolf catch a sheep. "Well, the wolf is eating you not me!" they think, as they shove and stretch to watch their fellow's fate.

This scene comes from Wolf Totem (trans- lated by Howard Goldblatt; Hamish Hamilton, £17.99), the story of Chen Zhen, a young Beijinger who has been sent to the Mongolian countryside to work as a shepherd in the 1960s. Chen Zhen falls in love with the grasslands and the wolves, whose spirit of independence and bravery he admires, and ends the book by raising his own wolf- skin flag, his wolf totem, into the wind.

Although they are divided by 86 years, the message in both books is clear: there is something rotten in the state of China. Jiang Rong, the author of Wolf Totem, is strident in his criticism of the devastation the Chinese have wrought in Inner Mongolia, where the ecological balance of wolf, gazelle, marmot and human has been destroyed, the grasslands turning to dust. You wouldn't expect a book so critical of Chinese government policies to be so popular, but Wolf Totem has been China's No 1 bestseller for the past four years. It has sold 4.2 million, with perhaps four times that number of pirated copies.

"I am not surprised by the success of the book," says Jiang Rong (whose real name is Lu Jiamin), as we sit in a tea bar in one of Beijing's swankier hotels. "The Chinese have always despised and demonised the wolf. The book subverts the reader's expectations. It divides people, and makes them talk and think."

It certainly does. Wolf Totem has attracted a lot of official criticism, with its author labelled a liberal, a traitor, an anti-revolutionary and a fascist. He is unfazed. "Most readers do not find fascism," he says. "Hitler thought the Germans were the best nation in the world; in my book, the Chinese have a lot of weaknesses. Even our national football team is sheepish. Hitler never described his nation as 'sheepish'."

"Sheepishness" is an oft-heard self criticism within China. What exactly does he mean? "The... sheep is without a sense of creativity and freedom," he explains. "It is the opposite of the individual and freedom-loving spirit of the wolf. Because China lacks democracy, and because the Chinese are sheepish, we have suffered the cruelty and deprivation of episodes like the Cultural Revolution. The Chinese need to incorporate more of the wolf spirit."

He switches into English to say "independence" and "freedom". Both are heady words to be saying in Beijing, but Jiang Rong is no stranger to controversy. "I am lucky to be alive," he comments, and this is no exaggeration. First branded a "counter-revolutionary" aged 18 for an essay he wrote in 1964, he was founder of the "Beijing Spring" reform protest in 1978 and narrowly escaped the death penalty. In 1989, he was prominently involved in the crushed Tiananmen Square protests, and earned another 18 months in prison for "counter-revolutionary" activities.

"I wouldn't join the Communist Party and I wouldn't even join the youth league," he says. "I don't like joining organisations." The son of two Communist Party workers from Jiading, near Shanghai, he has inherited stubbornness. "When the Manchu people invaded China, the Jiading united with nearby towns. But the other towns submitted and left the Jiading to fight alone. The Jiading people refused to let their children marry those from the neighbouring towns because they were untrustworthy.

"My father was nominated general of an anti-Japanese force," he says. "He led his army into the Communist Party because they were fighting the Japanese. But my mother was even more determined. Her father was a gambler and lost all the family's money... She moved to Shanghai and became an underground worker for the Communist Party. She died of cancer when I was 11. But she had a profound influence on my life because she gave me many books, and fostered my love of reading."

During the Cultural Revolution, Jiang Rong was thinking for himself, when that was a dangerous crime. "I still remember a quote by Lenin. 'One cannot become a real communist until one has read all the knowledge of humankind.' I thought that if Marx, Lenin, and Engels read a lot of books, then why couldn't I?" While other Red Guards were burning books, young Jiang Rong picked them from the ruins. He ended up with a library of 200 banned books. "There were dozens of books by Balzac, Pushkin and Tolstoy as well as many of the Chinese classics and histories."

It was partly the urge for freedom that led him to volunteer to go to the grasslands of Inner Mongolia in 1967. "It was a year before Mao sent the youth to learn from the countryside. I was inspired by US and Russian literature and especially And Quiet Flows the Don, by Mikhail Sholokhov. I thought I would be more free in a place without settlements. When we arrived in Inner Mongolia many Chinese students felt sad at the conditions we were in. But I was exhilarated because I loved the grasslands and the snow. Each of us got a horse and we went hunting. I experienced a tough and wild freedom. Everyone should be able to experience that freedom."

That tough and wild freedom is what becomes characterised, through Wolf Totem, as the "wolf spirit". "The most important thing in life is the capacity to be free... That individual freedom doesn't just include the freedom to make money. It includes the freedom of speech, the freedom of organisation. Wolf packs are strong because they operate in groups," he argues.

"The democratic revolutions in China have failed because the Chinese have not grouped together. On the grasslands and within the nomadic people, I discovered the freedom gene within Chinese society... The Wolf Totem is the Chinese Statue of Liberty."

Wolf Totem marks a new maturity within China: not only that a writer can pen a book so critical of his society; not just that this book can be a bestseller for four years; but also that this book has not been banned. "I was half surprised and half not surprised," Jiang Rong tells me. "I was surprised that the government discovered my real identity only very late. If they had known I wrote the book, then it would have been banned. Now, I do not hide my identity to foreign media, and in China on the internet my identity is an open secret."

Now that Wolf Totem is being launched in English, I ask Jiang Rong if he thinks there is a message to Western readers. He thinks carefully. "The Westerners do not understand the Chinese so well. You must have patience with China. The freedom gene does exist within China. We need to encourage it to grow."

He talks about how many changes there have been within China; how democracy is growing. A recent article from an officer in the Party's Central School said that by 2040 China will have realised the aims of democracy and a total market economy. When primary-school students held elections in their class, "They knew and used the same terms as is used for US presidential elections. They knew how to lobby and make speeches. These young people will be the pillar of democracy in China."

Despite the failures in his life, Jiang Rong is optimistic about the future of China. "Most people in the Communist Party believe that totalitarianism cannot last long. After one or two generations we will realise democracy and do away with dictatorship. I am very optimistic. The Chinese youth have a much greater sense of freedom than other generations."

He's less certain about the novel's environmental themes. The dust cloud over Beijing is a constant reminder of the desert dunes approaching the Chinese capital, now only a drive away from the suburbs. "The biggest conflicts ahead of us are not between countries or peoples but against environmental damage. Natural disasters will force countries to work together. It terrified me when I saw a thousands-of-years-old ecosystem turn into dust within a decade. My book is a lesson to the world."

Justin Hill's latest novel is 'Passing Under Heaven' (Abacus)

Biography: Jiang Rong

Born in 1946 in Beijing, Jiang Rong volunteered to go to Mongolia in 1967, "serving the people" in Mao's Cultural Revolution. He lived there as a nomad for 11 years. In 1978, he returned to Beijing to study economics, which he later taught at Beijing University. A founder of the "Beijing Spring" reform movement of 1978, he was prominent in the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, and served 18 months in jail. Wolf Totem, the epic first novel that draws on his life in Mongolia, stormed the Chinese bestseller lists in 2004 and has since sold four million copies. It won the Man Asia Literary Prize 2007; next week Hamish Hamilton publishes Howard Goldblatt's English translation. Jiang Rong lives in Beijing with his wife, the leading writer Zhang Kangkang.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments