Jean Teulé: And that's just for starters...

Jean Teulé tells Christian House how he was warned off researching his black comedy about a 19th-century act of cannibalism

In the Parisian bustle of a popular Jewish pocket of the Marais, a nondescript pair of blue double doors hides a cobbled courtyard at the end of which is a little shop.

In the last century it was a garage kiosk but now it acts as the office of Jean Teulé, a novelist who understands the power of revisiting historical sites for contemporary ends. Teulé invites me into a minimalist space. White walls, bookcase, pin board, iMac, and a neat stack of rolling tobacco. Above his desk hangs a single black-and-white photograph of a classroom of young boys.

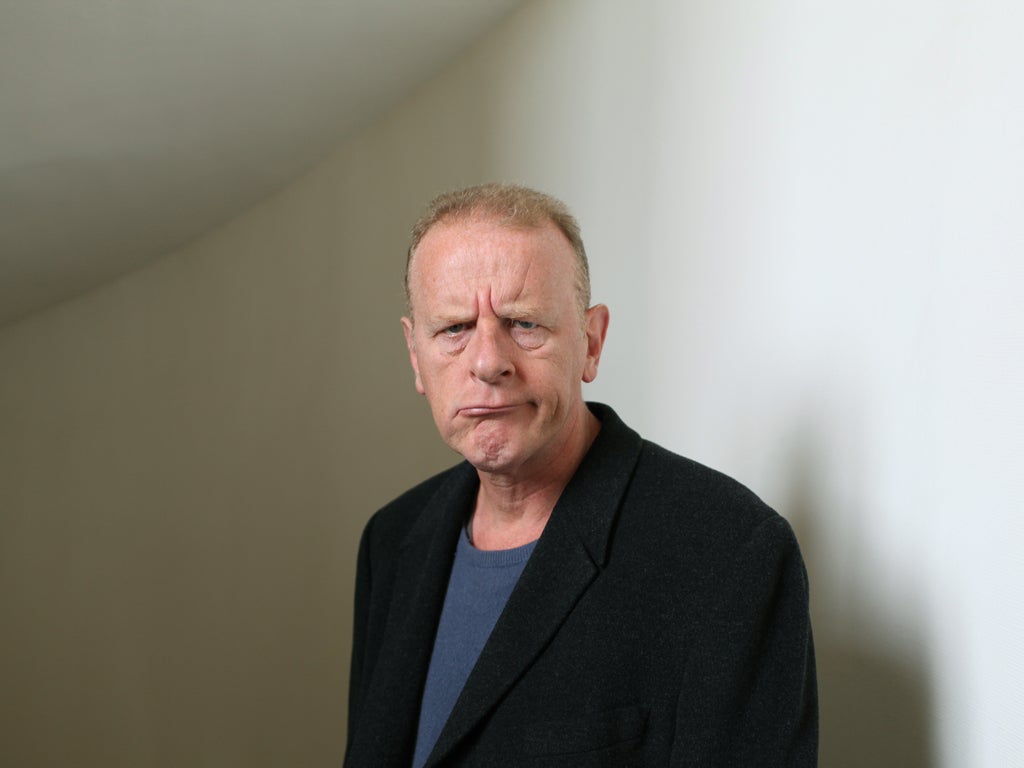

Teulé has all the bonhomie and cartoonish delight of a writer in his own little world. He is an idiosyncratic figure on the Gallic literary scene. A London publisher recently told me that he thought French publishing was in a slump. Teulé's bestselling novels such as Monsieur Montespan, the story of a lovesick Marquis cuckolded by Louis XIV, conflict with this diagnosis. A cozy looking middle-aged man with an infectious childlike laugh, his appearance is discordant with his morbid, comic dramas. His latest, Eat Him If You Like, is published in the UK in translation this week.

Acclamation led him to the source material for his new book. "After Monsieur Montespan had such success in France, I thought people would be disappointed. I thought 'I'm going to be lynched,'" says Teulé. "So I was looking on the internet at words such as 'lynch' and 'massacre', and fell on the village of Hautefaye." Eat Him If You Like, which tells the true story of Hautefaye, is set over one day of collective madness in the sauna-hot summer of 1870. France was at war with Prussia and the rural inhabitants of the small Dordogne commune were getting twitchy. When Alain de Monéys, a respected local landowner, rode in to the teeming Hautefaye fair he was unprepared for his fate. A slip of the tongue about France's chances and the drunken crowd turned on him. His neighbours became anarchists in their Sunday best.

Passed from pillar to post, ragman to notary, one unimaginable horror to the next, de Monéys endured an extraordinary demise. He was tortured to the bounds of human endurance and then, as he still clung to life, a bonfire was hastily built and he was burnt alive. Insanity, of course, but what has given the de Monéy's affair a particularly ghoulish place in the annals of French history is what happened next. The crowd took his burning fat, an awful kind of human dripping, spread it on hunks of bread and ate him like a party canapé. One reveller crunched on his steaming testicles.

Research was problematic, says Teulé. "In the village they really weren't happy. They didn't want the story to be known. And to scorn them, I would say, 'Well if the book works, I'll open a little restaurant and call it the Hautefaye Grill,'" laughs Teulé. "They said on local television that I had better not come back or there might be a second sitting. The current mayor wanted to put up a plaque to say that the village was sorry, but the villagers refused because it was their ancestors who were responsible. The book went out in May, and by August tourists were coming with their book asking: 'Is this the village of the cannibals?'" He cackles at the thought, and again when he explains that a Parisian brasserie has already named a dish the "de Monéys steak tartare".

Teulé relates to the victim. "I don't like crowds of people. I'd never go to a rock concert," he says. "A few months ago my train was late. After a while, they said that the train could be boarded. Everybody has their place reserved. The train was not going to leave, and yet everyone roared to get their seat. If one little old lady or man fell? I surprised myself by starting to run too. It's that mechanism of a crowd, like the cells in a body." He believes the Hautefaye story could reproduce itself, and gives the London riots as a case in point. "Mass can be heroic but it can also be strange and dangerous," he says. "That was the same thing. And it started from nothing. Just a little trigger and it blazes into a fire."

Teulé's milieu is centred on the "merriment of vice and cruelty". His novels are bawdy, full of rollicking sex and roiling violence. However, he undercuts this with a graphic humour born of his earlier career as an illustrator. "When I don't know how to write a scene I will sketch it and put it on my board. I will look at it and the words will come. I can't write a scene if I can't visualise it." The result is exceptionally cinematic prose. (Teulé's 2007 novel The Suicide Shop was recently filmed by Patrice Leconte.)

The petit salon swirling with cigarette smoke in which we sit is Teulé's retreat from the contemporary world with which he claims not to connect. Yet his private life is one that, at least on the surface, is Paris Match material. He is the partner of the celebrated film star Miou-Miou and his oldest friend is Jean Paul Gaultier. He points to the photograph of the Sixties schoolboys and there they are, the juvenile Jean and Jean-Paul, looking back at us with beaming smiles. It is the only picture either has in his study.

Teulé might orbit the cultural elite but he's most at home here in his dark corner. "I love to be out of the world. In my bubble. When I am between two books I don't feel comfortable," he says. His next bubble is inhabited by the Breton cook Hélène Jégado, who poisoned more than 30 people at random between 1833 and 1851.

"She said that everywhere she went, death followed her. I was in Brittany at a book signing and a baker from Rennes came and gave me a cake saying, this is the Hélène Jégado cake. But without arsenic," smiles Teulé. He explains that Jégado was executed on his birthday, 26 February. "Extraordinaire." And once again laughter bursts from Marais's merry messenger of death.

Eat Him If You Like, By Jean Teulé (trs Emily Phillips) Gallic Books £6.99

"Alain was living a nightmare. The behaviour of his fellow creatures plunged him into despair. Earlier, on his way to the fair and unaware of the horrific fate that awaited him, he had been lost in the most wonderful reverie. Now even the devil would have cried for mercy on seeing several of Alain's toes fly from Lamongie's pliers and hurtle through the air."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments