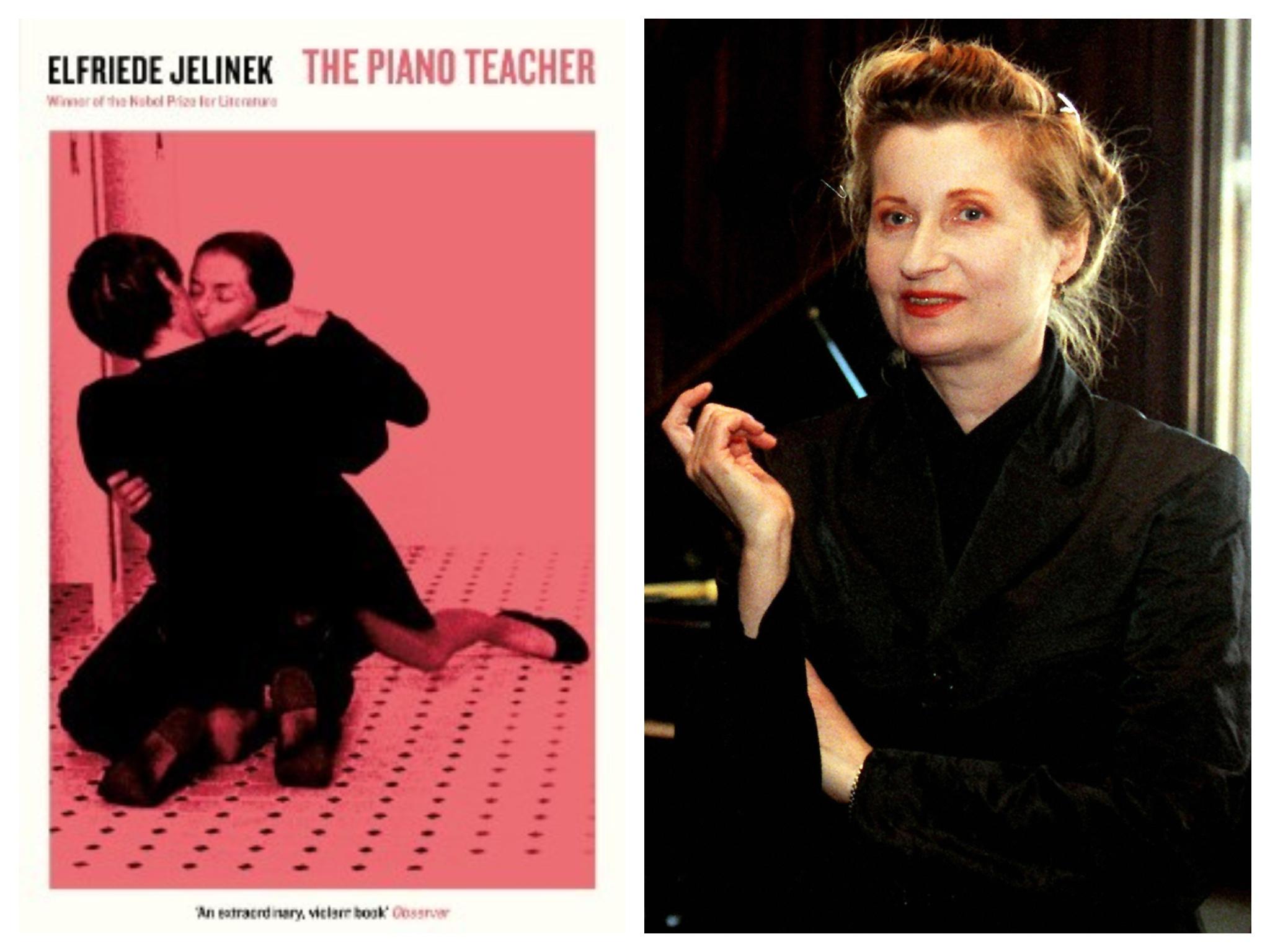

The Indy Book Club: Elfriede Jelinek’s brutal novel The Piano Teacher finds no feeling in violent sex

The detailed descriptions of sadomasochistic acts are so visceral that it can be an effort to turn each page, says Annie Lord. You flinch as though a razor were held up to your eyeball

Elfriede Jelinek’s The Piano Teacher is a disgusting book to read. In stark, unsparing prose, it plunges into the mind of Erika Kohut, a repressed piano teacher and failed concert pianist who self-harms and engages in sexual voyeurism as attempts to feel. In one scene at a peep show, she buries her face into a tissue containing ejaculate from the man before her. In another, she urinates from the excitement of seeing a couple have sex in a car. On the train home from work at Vienna’s Conservatoire, she discreetly kicks the shins and pinches the calves of tired workers, using her ladylike, buttoned-up appearance to feign innocence.

We meet Erika while the handsome, blond-haired engineering student Walter Klemmer is falling in love with her. After rejecting him several times, she writes him a letter detailing a series of brutal sadomasochistic acts she wants him to perform. What follows is so harrowing it can be an effort to turn each page. You flinch as though a razor were held up to your eyeball. Unsurprisingly, The Piano Teacher divides opinion. When Jelinek won the Nobel Prize in 2004, one member of the jury resigned over the decision, calling her work “whining, unenjoyable pornography” and “a mass of text shovelled together without artistic structure”.

Erika has no father: hers went mad, and was taken to an asylum in the back of a butcher van. Many critics apply Freudian theory to see the absence of a father and the presence of a psychotically overprotective mother as the reasons for Erika’s sadism. In a 1994 essay, Dr Kosta Barbara wrote: “Aside from the fact that the exclusive bond between mother and daughter remains uninterrupted and maternal domination obstructed, [the father’s] displacement suggests the cause for Erika’s failed separation from the mother and her excessive masochistic drive.” In this way, The Piano Teacher is a critique of the tendency in 1970s and 1980s psychoanalysis to idealise the pre-Oedipal mother-daughter bond. Here the womb is unfettered, and the consequences of that are bloody.

When she’s not out stalking the streets of Vienna, Erika lives a comfortably miserable life indoors with mother. The opening sequence sees the unhappy couple fighting over Erika’s luxurious new poppy-patterned dress. Mother cries “vanity!” and tries to twist the garment out of her daughter’s convulsed fingers. Furious, Erika yanks at the “discoloured dark blond tufts” of mother’s hair until chunks of it waft out into her hands. Unsure what to do with the hair she “goes into the kitchen and throws them into the garbage can”. Her mother weeps on her knees.

You feel bad for the elderly woman until you hear what she’s done to Erika. When her daughter was young she never let her have fun. All Erika had was Bach and Beethoven and “play it again!”. Now that her daughter is an adult, this fork-tongued harridan stalks her every move; hoards her earnings so one day she might buy a better apartment; nags her, day and night; forbids her from seeing men. As Jelinek puts it: “The daughter is the mother’s idol and Mother demands only a tiny tribute: Erika’s life.” Mother sucks the bone marrow from Erika, and inside the daughter dries until she cracks to pieces.

They make up, though, because they love each other as much as they hate. Each night they relax into two easy chairs and watch as “the lead-in for the news plays softly”, taking turns to grab gumdrops from a bowl on the side table. “This is Never Never Land,” writes Jelinek “where nothing ends and nothing begins.” At night they collapse into the same bed – hands strictly above the duvet so Erika can’t touch herself. They’re two exhausted lovers who take everything good from each other. Erika is floating in the amniotic fluid. It’s a trap. It’s one she can’t get out of.

Here’s what some of our readers thought...

Mark, 47, Hull

Elfriede Jelinek writes in a stream of consciousness style without speech marks. This makes it hard to distinguish whether it is Jelinek who is thinking or her characters. It is also written in a non-linear form, but without making use of the flashback. Instead, it relies on purely contextual evidence to orientate us towards the correct temporal place in the narrative. I found it very confusing and prefer more traditionally structured texts.

Vicky, 28, Dover

This book got under my skin and it’s so horrible I don’t really want it to live there. Jelinek makes use of such precise and arresting images you feel like you’re watching a film. I would have rather vague, muddled words so that I didn’t have to keep returning to the novel’s horrific scenery every night before falling asleep.

Maisy, 34, London

When I was growing up my mum was immensely controlling. She wanted to know where I was going and when I was going there and boyfriends were never allowed. Like Erika, I have found that I am emotionally closed off. Friends joke that I am the “Ice Queen” and I laugh but sometimes I worry about how far away my body feels. Erika tries to solve this through violence. I don’t know if the same would work for me.

Our next Indy Book Club pick will be voted for by you. Send your thoughts to annie.lord@independent.co.uk

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies