How children’s literature with a social conscience galvanised a generation and changed the UK

A new genre of leftist literature arose between the wars, urging the young to build a brave new world. In the first of two articles, a forgotten dream is remembered

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Children’s books often fly beneath the cultural radar, belying their ability to work powerfully on the social imagination. In the McCarthy-era US, for instance, they provided both a safe haven and a platform for writers and illustrators whose work was out of favour with the establishment. Subsequent studies suggest that the progressive views many American children absorbed through their books shaped the generation that protested against the war in Vietnam, supported the Civil Rights movement and campaigned for equal rights for women.

The fact that children’s books can have a strongly formative influence upon the young has often attracted the attention of new leaders and regimes. In the early days of the Soviet Union, Lenin and his followers harnessed the power of children’s books to shape culture. Some of the artistically vibrant work that resulted from co-opting leading writers and artists is currently on exhibit at London’s House of Illustration with the title, A New Childhood: Picture Books from Soviet Russia. In interwar Britain too, a group of socially and aesthetically radical children’s books underpinned the work of making Britain a progressive, egalitarian, and modern society. But unlike their Soviet counterparts, these books have since remained a largely hidden secret, with most scholars of the period overlooking them altogether.

In fact, there were many children’s books published during that time that sought to use writing for children and young people to create activists, visionaries and leaders among the rising generation. These radical children’s books were created by writers and illustrators drawn from many quarters, including working class socialists, the liberal intelligentsia and prominent cultural figures, from Hugh Gaitskell through JBS Haldane and WH Auden. Drawing on the latest ideas from the spheres of science, politics, economics, pedagogy, social policy and literature, as well as the fine and applied arts, they encouraged young readers to look with fresh eyes at how people were living, interacting, and organising themselves. They were not only concerned with engineering social change but also sought to transform how the world was perceived. Aesthetically radical works continued the general project of widening youthful horizons by celebrating children as artists and introducing aspects of the new arts associated with modernism.

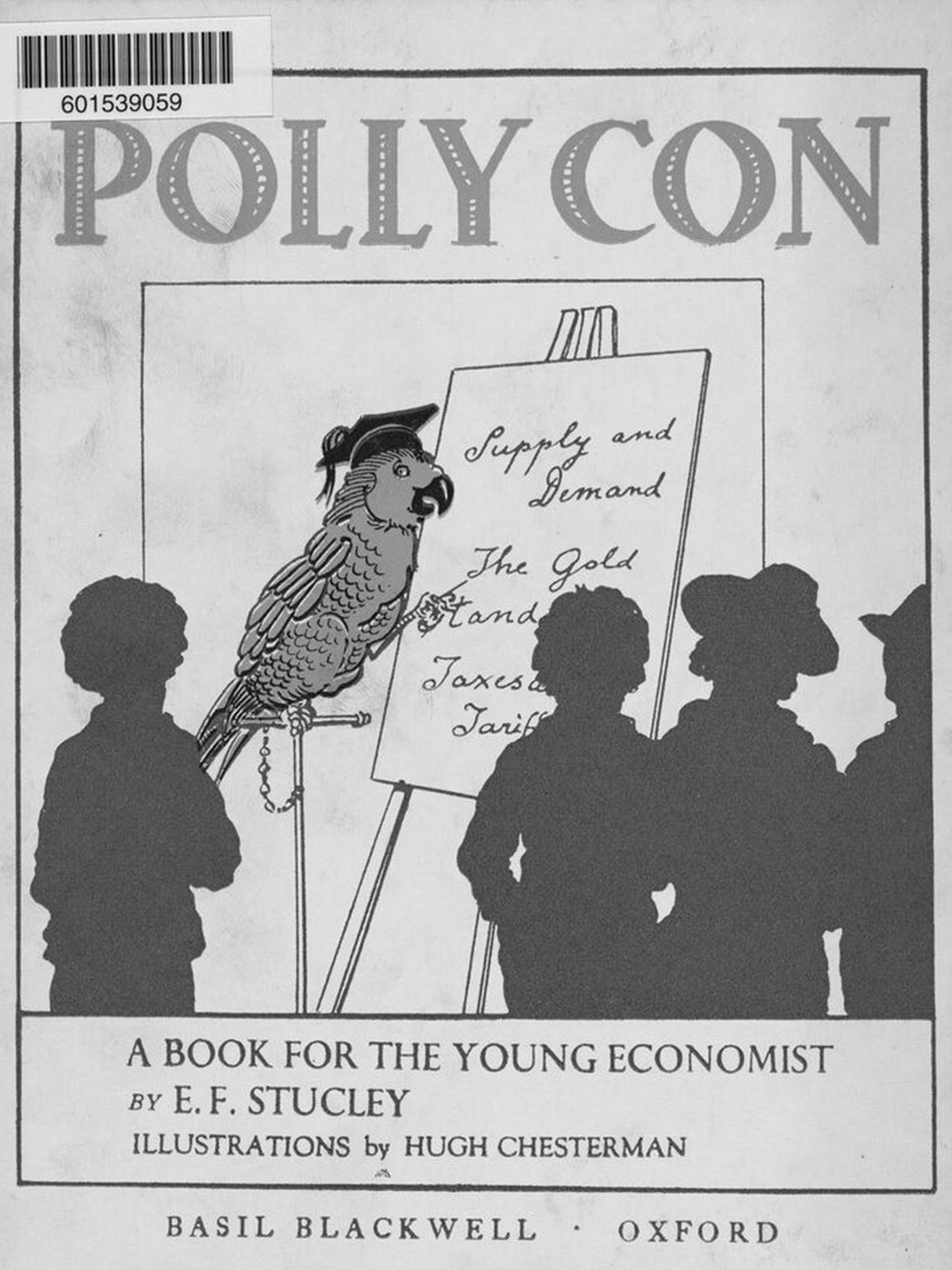

These radical works included books opposing war, and books about modern architecture and design, class and unemployment, children’s health, sex education, the countryside, and all the sciences. EF Stucley’s Pollycon (1933) is one of a number of books that sought to teach children and young people the principles of economics because, as Stephen King-Hall, a popular radio presenter of the day, declares in the book’s preface: “I cannot tell you too often that you will be a stupid ass if you do not make up your mind to learn about Economics.”

As here, radical children’s books assumed an audience of intelligent, capable, socially aware young readers and set about providing them with the skills, information, and inspiring social visions they would need to find solutions to the many problems confronting the world; problems that eventually resulted in a second world war, a global financial crisis, and mass social unrest and protest. They set about breaking down stereotypical attitudes to gender, race, class, poverty, ethnicity, nationality, and childhood.

One example is Martin’s Annual (1936), named for its leftist publisher, Martin Lawrence. This volume included stories about young freedom fighters and others who oppose fascism; lessons from nature in how the small and weak outwit the large and strong; a warning against the seductions of military recruiting regiments; accounts of Soviet heroes; cartoons deriding the Blackshirts, and a detailed critique of Britain’s national anthem. There were also comic poems, a revolutionary alphabet, recipes for healthy eating and a competition to find juvenile proletarian writers.

Then there’s Eddie and the Gipsy, by Alex Wedding – a 1935 book translated from the German in which, as the title suggests, a boy called Eddie becomes friends with a Romany girl. Illustrated with photographs of real children by John Heartfield (better-known for his anti-fascist montages and bitterly satirical images of Hitler), it captures the tensions in Germany during the Nazis’ rise to power and promotes trade union activism – forbidden under Hitler – as well as friendship across racial divides.

But Geoffrey Trease is the quintessential example of a radical children’s writer of the time. A founder member of the Promethean Society, a group for pacifists, humanists, and devotees of Freud, Marx, Wells, Shaw, Lenin, Trotsky, Gandhi, Havelock Ellis and DH Lawrence, in later life he recalled, “We believed … that the world’s poverty could be cured by a simple change in the financial system. War could be abolished by disarmament … and by non-violent demonstrations such as lying down in front of troop trains.” The rueful tone gives voice to the sense of disillusion felt by those who, like Trease, having hoped for so much from the Soviet experiment, saw it descend into show trials, the Great Terror and the Cold War.

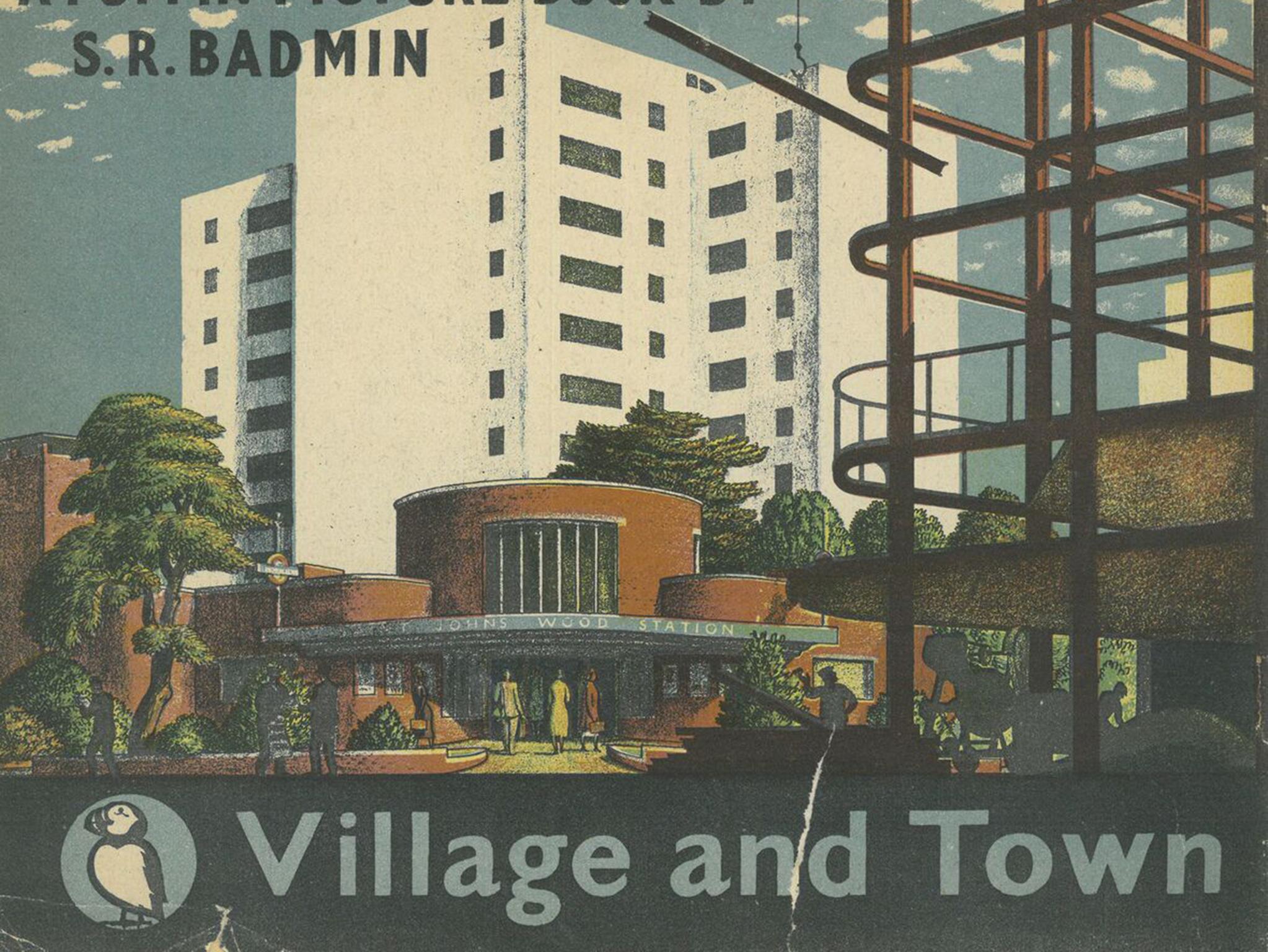

Before that realisation, however, radical writers inspired British youth with a panoply of ideas and images of what the future could be like. Trease’s Bows Against the Barons (1934), a retelling of the Robin Hood story which uses the Middle Ages to talk about the Depression, includes a vision of a future in which “the common people will have twice as much as they have now, and there will be no more hunger or poverty in the land”. And many of the popular Puffin picture books encouraged children to think about how they could do things better when they had grown up and were running the country. SR Badmin, for example, ends his Village and Town (1942) with the questions: “Do you know we could have much better houses if they were well designed…. we could have towns which were clean and smokeless … which had plenty of playing grounds and no slums? …. Look at your own home town. Surely something better must be built next time?”

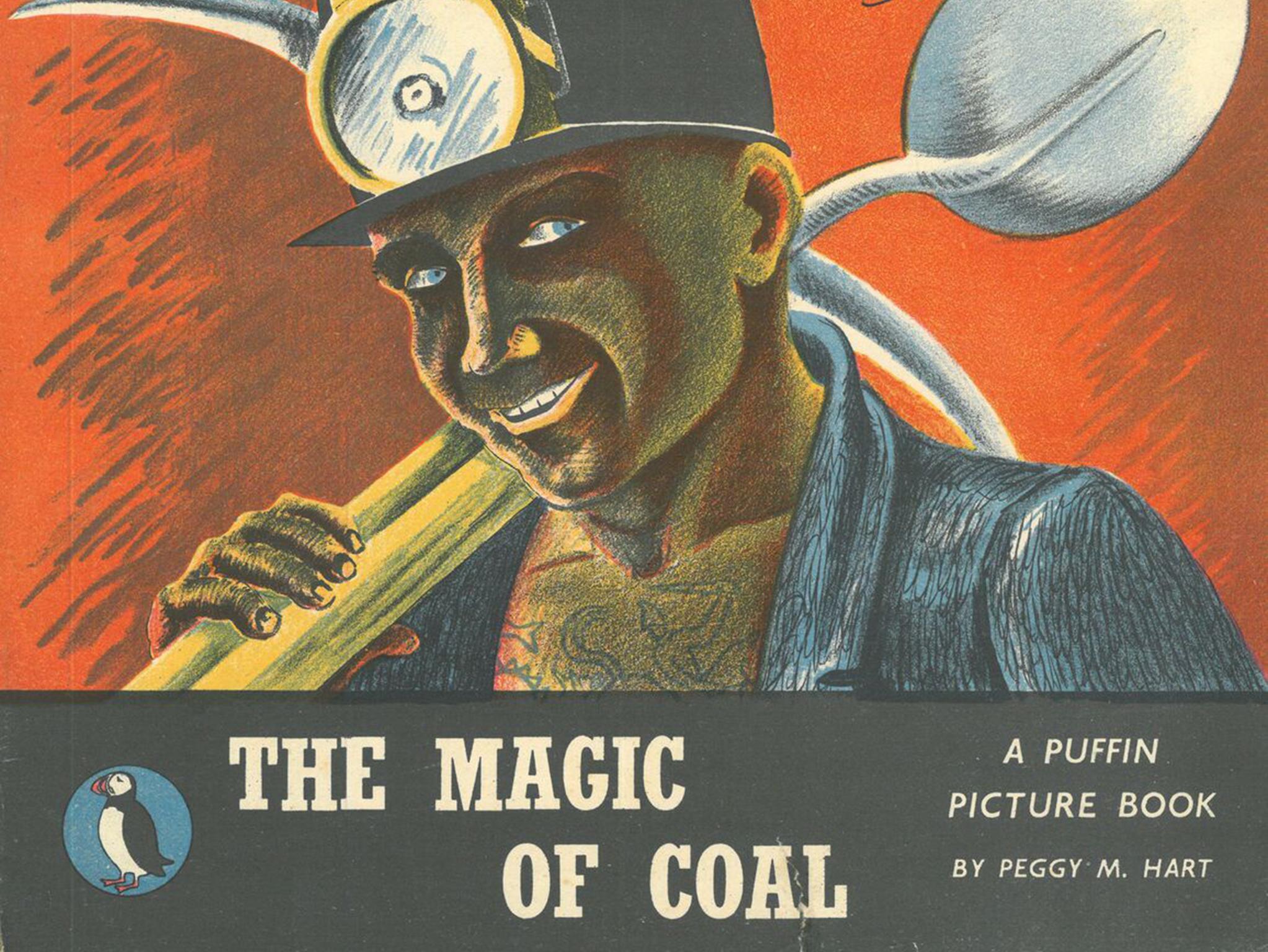

Peggy Hart’s The Magic of Coal (1945) shows a future in which the mining industry has become fully technologized, collectivised and sanitised. The cover image features a broad-chested miner with a tattoo of St George fighting a dragon on his chest, making miners modern day heroes and emblems of Britain. Miners are shown enjoying the facilities in the pit baths before setting off to nice homes on “fine” housing estates or to participate in activities including higher education classes and watching plays.

In the 1940s, interest in producing radical children’s literature receded as the kinds of futures they imagined move from the page into real life in the form of the emerging Welfare State. The 1942 Beveridge Report set out a series of milestones which became the 1944 Education Act (free secondary education for all), the National Insurance Act (protection against illness and unemployment), the building of the first council houses and the National Assistance Act (which provided for anyone in extreme poverty), culminating in the official launch of the National Health Service in 1948.

These texts may seem quaint now but we should not forget their legacies; indeed, there are lessons to be learned from them still. Compared with today’s output of gorgeously produced and varied children’s books they might look rather humble and earnest – but there is something deeply attractive about their aspirations for children and the future. Childhood reading develops intellects, imaginations and tastes. The generation for whom these radical texts were written was responsible for seeing that the young Welfare State flourished, for making Britain part of Europe – at least for a time – and for placing it at the centre of youth culture and fashion. Geoffrey Trease could only imagine a distant future when life would be better for ordinary people, but by 1949 Britain was a genuinely fairer place with cradle-to-grave care and world-leading, child-centred primary education.

While the hopes and ambitions for lasting peace and global government featured in these books may not have materialised, the vision of a more socially just and progressive society that lies at the heart of radical children’s writing continues to shape Britain today. The part played by radical children’s literature in this social transformation deserves to be remembered and perpetuated. Rarely has it been more important for the rising generation to be well-informed, to master new technologies and to be prepared to help with the work of making the world safer, fairer and more sustainable. Today we are blessed with a wealth of writing for the young, but much of the most socially engaged, forward-looking writing takes a dystopian stance. Young readers today could surely benefit from the same determination to inspire progressive thinking – and a belief that the future can be better than the present if they will help make it so – that characterised this forgotten chapter in the history of children’s publishing.

In next week’s article: Reading and rebellion

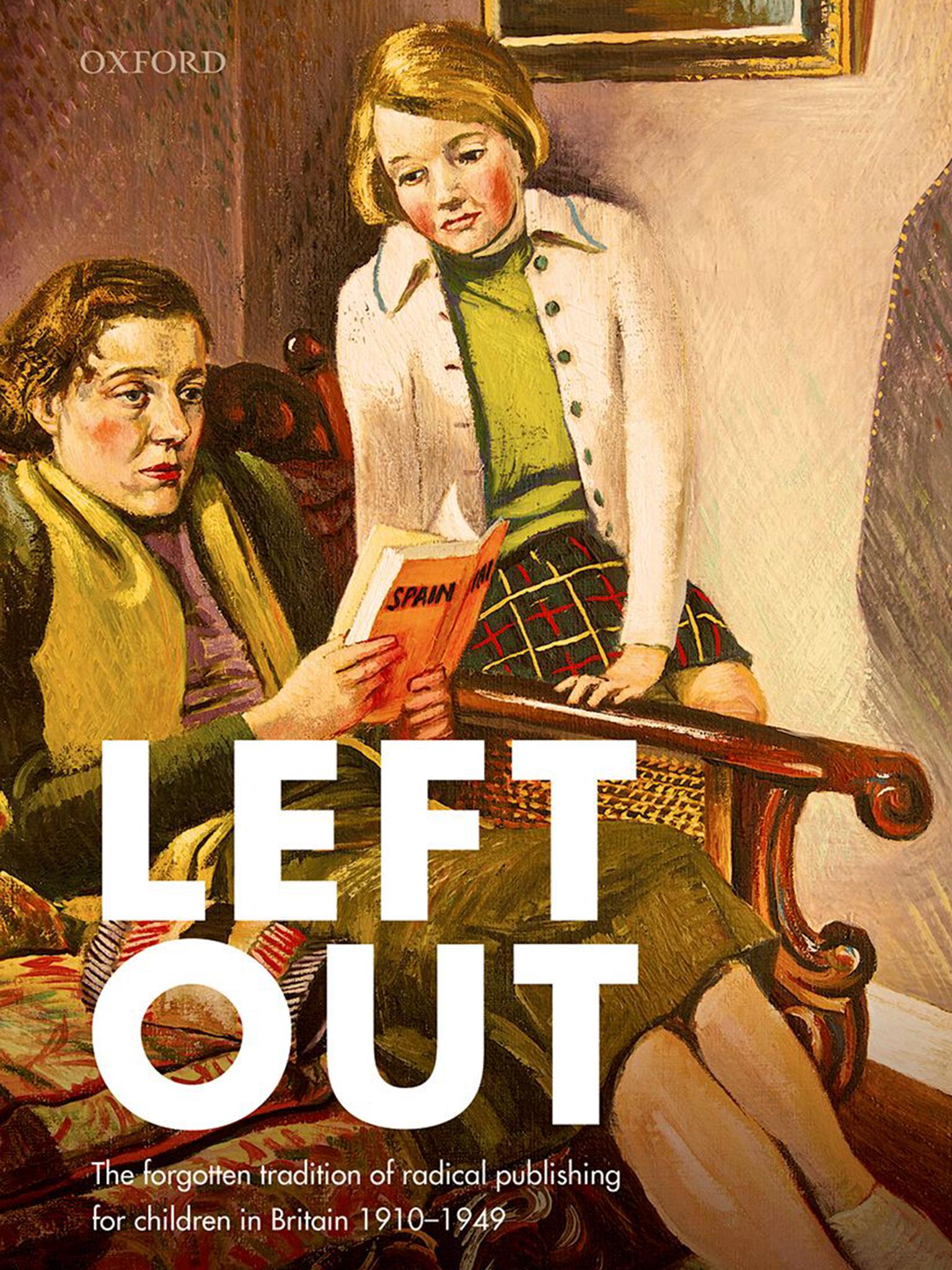

Kimberley Reynolds is the author of ‘Left Out: The Forgotten Tradition of Radical Publishing for Children in Britain, 1910-1949’ (Oxford University Press, £35), to be published on 28 July

‘A New Childhood: Picture Books from Soviet Russia’ is at The House of Illustration, 2 Granary Square, Kings Cross, London N1C 4BH until 11 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments