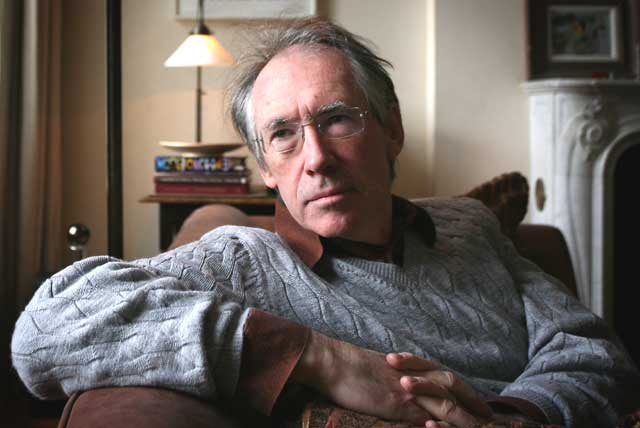

Hard science and soft humanity: At home with Ian McEwan

Ian McEwan's new novel, Solar, satirises the low compulsions of an absurd scientist but celebrates the high aims of scientific research. Boyd Tonkin meets the 'imaginative rationalist' of British literature

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.'Bald, short, fat, clever", Ian McEwan's latest protagonist gorges on junk food, routinely cheats on his myriad wives and lovers, robs a dead employee of his breakthrough ideas about cheap renewable energy, and rests in his randy, portly way on the laurels of the Nobel Prize in physics that he won many years before. Surely no biographical truth could ever match this florid fiction? Yet McEwan, the most consistently science-friendly major writer of his age, has even at this early stage felt the shock of recognition from his collaborators on the other side of the "two cultures" divide.

"A couple of them have already written to me saying, 'I'm a bit worried that your Michael Beard rather resembles so-and-so down at the Centre'," he says as we talk. A warming carbon-fuel fire burns in the sitting-room hearth of the corner house on an august London square where he lives with his wife, the author and journalist Annalena McAfee. (He gave this same address in his novel Saturday to a far more upright scientific hero, the neurosurgeon Henry Perowne.) After those emails, "I thought, Oh my God! But fortunately, two or three individuals have been named." Libel lawyers should not hoist their hopes too high. "I seem to remember that Flaubert was faced with almost 40 lawsuits from pharmacists who all thought they were Monsieur Homais [the pompous schemer from from Madame Bovary]. So that's self-cancelling."

A selfish and greedy hedonist who can by his pampered mid-fifties no more pursue an original theory than he can see his own toes, Beard still seeks to serve humankind by harnessing the power of our near star for cheap, safe energy and so consummating a "cranky affair with sunbeams" that began in his shining student days. Long awaited and avidly debated, McEwan's Solar is a fiction in which climate change and the wavering human response to it supply what he calls "the background hum". Both a comedy and a parable, his 12th novel enlists an array of headline issues and a repertoire of trademark McEwan-esque torques and wrenches to tell "a story of hubris, folly, and something intrinsic in human nature". Absurd but not quite irredeemable, Beard comes to stand limply for all our planet-threatening, stuff-your-face proclivities. On a short flight back to London from Berlin, for instance, he wolfs down an entire premium-fare meal, champagne to chocs, after his dietary good intentions last for 10 nanoseconds or so. Only the grapes remain untouched. "In business class now," comments McEwan, "they put before you a bowl of heated salted nuts. Try resisting those."

A hypocrite and a rogue (or "complete bastard", as his creator puts it), but one whose mind still takes him down the road to truth, Beard will emerge into intellectual weather rather different to the conditions that bred him. Three years ago, McEwan's virtuosic early-1960s period novella On Chesil Beach came out (he's currently at work on the screenplay of a film, for the director Sam Mendes). Then, he told me of his intention to write some kind of fiction around climate change. The grandest conceptions of modern science, and their precarious habitat in our frail skulls and frames, had after all loomed large in the unfolding of his fictions at least since his 1997 novel, Enduring Love.

Often he has shown how our embodied minds aspire to intellectual miracles and then sink down into the mortal mechanisms of impulse and instinct, of blood, tissue and bone. Blessed and cursed by the housing of spirit in flesh, McEwan's mid-period heroes in their Darwinian dramas reach high and stoop low, "the beauty of the world, the paragon of animals", as Hamlet has it, but always as well "this quintessence of dust". "Accepting the 'embodied' argument also opens up for the novelist a much richer field than thinking of your characters as brains on plates, just minds," McEwan says. "Owning a body becomes a more onerous affair as you get older, of course – it gets fatter, heavier and iller. Life becomes impacted by resolutions that are carried out feebly."

Given his outlook and his gifts, how could McEwan avoid the slow warming of the planet: that arena in which human dreams and hopes run up most bruisingly against the laws and limits of the physical world? All the same, "I was having difficulty thinking how on earth one could do this subject," he recalls. "It seemed too intractable for fiction: too serious, too impacted with statistics, figures, science – really hard science too. Most of all, it seemed rather unwieldy because of the moral weight of it."

Shunning the dystopia and apocalypse as over-familiar dead ends, even in 2007 he saw the scope for humour and fable rather than breast-beating earnestness. Solar more or less conforms to the recipe he sketched back then – sharp, droll, even skittish, but with an undertow of sadness and even dread beneath the satirical surf. A princely has-been, burnt out but still flattered like royalty, Beard may owe just a little to the Nobel laureates McEwan met at a conference at Potsdam in 2007 organised by his friend John Schellnhuber, the German government's climate-change adviser: "I was the after-dinner entertainment." There, "I was struck by how grand they were – some of them comically grand in the way neither Seamus Heaney nor J M Coetzee are. They run fiefdoms in a way that writers can't, or don't – or shouldn't. These guys were politicians as well as scientists."

Among the secular idols, "I really got the sense of a glow of holiness – rather like in medieval paintings. The glory is almost tangible... Within their field, they are demigods. They do live an enchanted life."

What has altered since that formative moment, when the character of Beard "emerged from the gloom" on the plane back from Berlin, is the mood of lay opinion about man-made temperature shifts. Beard the double-standard baby-boomer, a cosseted child of an "arrogant, shameless, spoiled generation", might to some mischievous eyes look like the fictive answer to a climate-change denier's dream.

McEwan remains adamant. To him, genuine "scepticism" remains an honourable position. But the current gale of doubts and sneers about the intellectual edifice behind climate-change theory has no validity at all. The spats over leaked internal emails at the University of East Anglia (where the novelist became the first-ever student on Malcolm Bradbury's postgraduate creative-writing course) he treats as trivial academic rivalry. As for the now-notorious error over the pace of glacial retreat on the Tibetan plateau in an IPCC (International Panel on Climate Change) report, he dubs it a "serious mistake" – but turns his gaze to the motives, and the methods, of the "deniers".

Above all, "The denier case is just parasitic... They do not send satellites up; they do not crawl across the planet trying to make these difficult measurements, even though they are hugely funded by bodies like Exxon and energy-lobby think-tanks. Let's all be sceptics. Present some data. Do some measuring. Show us that the earth is getting cooler or staying the same, and that this is just an uninteresting fluctuation. The case really has to be made the other way round. We know the physics by which a molecule of carbon dioxide traps radiant heat. And we know that we put lots of carbon dioxide into the air, trillions of tons. We would expect the climate to shift; we see it happening. So the burden of proof is really the other way around."

McEwan's role as British literature's prime champion of scientific theory and practice has a cutting edge these days. A satirical segment of Solar draws on his 2005 trip to the Svalbard archipelago as a guest of Cape Farewell: the project that brings creative types face-to-face with the actuality of global warming amid the thinning Arctic ice of the 79th parallel. Only a reader (or colleague) who had suffered a triple sense-of-humour bypass could object to the motley crew of hippy-dippy ice sculptors and conceptual choreographers with whom Beard shares a symbolically messed-up boot room on board ship ("Only good laws would save the boot room. And citizens who respected the law.").

Yet a later episode, when Beard voices mild support for the evidence of sex differences in the aptitude for science and maths, has an altogether angrier buzz. The scientist's assumed sympathy for "genetic determinism" sees him pilloried by a radical audience at the ICA and vilified in the media as a "neo-Nazi professor". McEwan is drawing on his own, and friends', ordeal by media here. Media rows "have an almost addictive quality," he says. "It's very unhappy to have a storm blowing through your sitting room. And then it all stops. The beast has just looked at something else and suddenly left a calm. You think, 'What was that about?'".

As for today's intellectual liberal-left, McEwan alludes with distaste to "The automatic hostility to speakers because they're Israeli. There's a shocking aspect to some corners of British public life, and a sort of stirring of anti-Semitism on a mild scale." Mostly, however, Solar shows how "blank slaters" who believe that nurture accounts for everything and nature for nothing target those scientists, and their allies, who wish to investigate the ways in which genetic inheritance might shape our selves and skills. When these "innatists" first "raised their heads above the parapet in the Seventies," McEwan believes, "the left just reached for its automatic swear-word. They were Nazis. E O Wilson was called a Nazi: a deeply humane man and a great biologist."

Solar proves that McEwan has not softened his scorn towards the sort of postmodern philosophy that presents the objects of scientific research – even genes themselves – as mere "social constructions": "There's a daftness about it." He tried out these ideas on his elder son, William (one of two, now in their mid-twenties), a geneticist now based in Cambridge. "The scientists don't really know about this stuff; it doesn't come their way. So the philosophers of science are quite a closed group who go around talking to each other."

Although vain, foolish and dishonest, pudgy old Beard does thus get to share several of McEwan's firm convictions. A tender reverie about his first marriage has the washed-up Nobel laureate remember how he wooed lovely Maisie, an English student at Oxford, by mugging up on Milton in a week. Does his contempt for soft artsy courses reflect a consensus among scientists? "It's not among scientists – it's among me. I have this suspicion that people like you and me had, as undergraduates, a very easy time. I see it among my children's generation. You do a soft subject like French or English, you tumble out of bed at midday for three years, you have occasional panics with essays and a bit of reading. But on the whole, you're on holiday compared to the scientists."

When Will studied biology at UCL, 9-5 lectures, practicals and weekend work meant that "It's a job – and a whole body of knowledge is being absorbed." Meanwhile, in Solar, "I honestly felt a slightly wicked and not entirely defensible impulse to say: it is a lot harder to get your mind around the General Theory of Relativity than to understand Paradise Lost."

Discipline, diligence: good order in the boot room of the mind. However grotesque the states of delusion or denial that his fiction dissects, a fiercely rational and architectural intelligence always gives them shape. Ian McEwan, at 61 still very much the wiry hiker, is an "army brat". Born in Aldershot in 1948, the son of a career soldier from Glasgow who survived Dunkirk (and whose experiences fed the battle scenes of Atonement), the young writer emerged from a base-hopping forces childhood across three continents. At UEA, and afterwards, he polished his prose and cultivated his plots with a dedication to craft that gave the wild counter-cultural adventures of the mid-Seventies stories in First Love, Last Rites or In Between the Sheets an awesome sense of precocious control.

From an early stage, his sumptuously textured language rested on a flair for finely engineered design. At the finale of Solar, he has to herd Beard, his lovers and his foes together into a border backwater in New Mexico, "to choreograph a set of disasters". McEwan compares this narrative dexterity to plate-spinning: "I began to think, as I've thought in the past, I mustn't step under a bus until I get this done. Don't choke on the sandwich!"

What about the science behind this sorcery? In the US, Beard has developed an industrial-scale application of artificial photosynthesis that promises to make simple water into the next oil. "It's happening in a handful of labs," the author reports. Indeed, an MIT team made a relevant breakthrough as he wrote the novel. Still, "There's no real photosynthesis plant up and running. The trick is to find materials that mimic chlorophyll and do just one stage of photosynthesis. If we could split water cheaply, we would have a colossal amount of energy. So the dream has some basis in science."

In the non-fictional world, McEwan can see few heavy-duty alternatives to fossil fuel, save for the one source that he once denounced. During the missile jitters of the early Eighties, he wrote the anti-nuclear oratorio "Or Shall We Die?" As for civil nuclear power, "I started out very much against it." But now, "There isn't that much else on offer." He recalls, "I was at the top of the Post Office Tower at the end of last year: a beautiful, clear night; freezing cold. I was looking miles in every direction at glittering London and thought, how beautiful it is. How can you run this? Not with wind generators tonight. If you want not to burn fossil fuels alone, you only have one other powerful source."

What about the risks? "I don't think we should scare ourselves with a handful of failures. Far more have died in coal mining and the burning of coal. There are over 450 nuclear power stations in the world and they generally work fairly well. The problem with nuclear has been its links to the armaments industry, and the lack of openness and transparency: the lying one always associates with the nuclear industry – lying about costs, lying about leaks."

McEwan's nuclear option, which follows the reluctant atomic embrace of green gurus such as James Lovelock and Stewart Brand, still leaves space for private commitments to a low-waste lifestyle as "a way in which everybody can engage with this at some personal level... But it's not the solution. It just means that we'll get to where we're going two years later." Besides, "Having a dog is more energy-inefficient than having a SUV. Six million people are not going to get rid of their dogs."

Still, several millions may give house room to a novel by Ian McEwan. His stature and popularity at home, which spiked sharply after the canonical grandeur of Atonement in 2001, goes along with an ever-rising profile abroad. Around our feverish planet, readers of Solar will grasp that the faults and follies of scientists do not demolish the value of their work. The message could hardly be timelier. "You can't have a conspiracy of scientists," the imaginative rationalist insists, praising the peer-review process that secures an open forum for fresh ideas. "They're always tearing each other's stuff down... It works by slow accretion and endless fine adjustments. We don't have another thought system that accepts error, and adjusts itself and realigns itself in the light of new data, in quite the same way. Religions don't. They bed down with sacred texts." In fiction, McEwan accepts nothing as sacred: except the quest for truth.

The human animal: the verdict on Solar

We should turn the headline story on its head. It's not so much that Ian McEwan has written a novel about climate change. Rather, climate change has generated an Ian McEwan novel: one that, for all its fresh angles and unexpected comic sidelights, belongs in the centre of his imaginative world. Readers who have partnered him on a 35-year journey that began with the exquisite perversities of his early fiction know that the study of human systems and their potential for breakdown – the body, the mind, the family, society – lie close to the core of his concerns. Animals and intellects, bio-machines doomed to dust with big, unruly brains attached, McEwan's people tend to evolve in the direction both of high achievement – in art, science, politics – and of dangerous excess: the fanciful invention (Atonement), the lethal obsession (Enduring Love), the crippling trauma (On Chesil Beach).

In Solar, Michael Beard, the fleshy Nobel laureate in physics with his path-breaking innovations long behind him, becomes a sweaty, lustful, snack-addicted microcosm of the warming Earth itself. He, and we, just don't know how to stop. And his many women, lightly but deftly drawn, symbolically indulge his gross indulgence for the sake of his tangy aura of charm and fun and glamour. He is a sort of walking packet of salt-and-vinegar crisps: his favourite, fatal junk food.

We meet him in the midst of another marital meltdown, as his fifth wife, Patrice, cuckolds him with a builder. The two men's testosterone-flooded stand-off (another regular McEwan standby) leads obliquely to the violent death of someone else: a scene of close-focus, stop-motion panic and adrenalin of the sort that recurs throughout his work.

Along with this microscopic intensity, McEwan excels at the telescopic overview. Here, Beard's lingering devotion to the "pure beauty" of his science, and his rejuvenating mission to mimic photosynthesis, pays rich fictional dividends. From the panoramic view in a circling plane of sprawling London and its "hot breath of civilisation" to the excitement of R&D, as Beard and his American backer plot the realisation of their dream of "cheap, clean and continuous energy", the broad picture of our plight coexists with high-definition domestic detail. The (often consumption-related) contrasts of scale – the great thinker snaffling another man's snack on the airport train; the grotesque pile of pancakes in the US diner as the day of humankind's salvation (potentially) dawns; Beard's agonising quest to take a leak in the deep freeze of Spitsbergen – fuels the comic motor that always purrs beneath the novel's big ideas. Poised between high theory and low farce, Beard's story (and the planet's story) pants and waddles towards its end not with a bang but a whimper – and a chuckle, and a wheeze.

'Solar' by Ian McEwan is published by Jonathan Cape (£18.99)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments