European novels - Seeking harmony on the hillsides

In 1940, Britain and France might have merged; in 2010, European splits seem as deep as ever. Could culture heal the rifts? Boyd Tonkin reports on a French quest for a prize-winning 'European novel'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Today, President Sarkozy arrives in London to celebrate the legendary appel de Londres of 18 June 1940: the broadcast with which the self-exiled General de Gaulle, in front of a BBC microphone, began to rally his compatriots to Resistance in the face of Nazi occupation. Three days earlier, however, Winston Churchill himself had authorised a startling secret proposal to his beleagured counterparts in Bordeaux during the last days of French liberty before the armistice with Germany. In a last-ditch effort to stiffen resolve, he had offered the ultimate "special relationship": nothing less than full political union between France and Britain. The author of this mind-bending plan was a London-based financier-turned-technocrat who, in later years, would earn the wrath of Churchill's self-appointed heirs as his even wider vision of a "European Union" progressed step-by-step from blueprint to reality: Jean Monnet.

Monnet, the intellectual architect of the EU, saw economic and political cooperation as stages on the route towards a cultural integration made necessary by the bloody mess that a rivalrous, divided continent had made of itself in two world wars. Now, in 2010, the political part of his project has well and truly stalled. As far as economics goes, the Eurozone catastrophe seems to have thrust it into reverse. So what remains of culture?

It would be a truism to say that, over the decades, EU spending on the arts has bankrolled plenty of lumbering, artificial beasts – from misconceived "Euro-pudding" movies to jolly but ineffectual talking-shops – without ever creating much in the way of pan-European practices and standards. So much the better, say the sceptics; tant pis, the federalists reply. And, if art forms stubbornly refuse to integrate when – in music, dance, painting or sculpture - they share a universally accessible language of expression, then what of literature?

Here, Babel still reigns. The direction of EU policy – the protection of minority tongues; the (slightly hypocritical) erection of bulwarks against the domination of English by Eurocrats who do most of their business in that language – has aimed to entrench diversity. Oddly, it's the commercial marketplace in books that has done most to build a shared European space for readers – and not just, as you might imagine, by carpeting the continent with translated Anglophone potboilers from Lisbon to Lodz.

A new report by Rüdiger Wischenbart, a Vienna-based book-market researcher and consultant, shows that of the 20 bestselling authors across seven major European markets for April 2009 to March 2010, only five write in English – and, post- JK Rowling, not one is British. "The often heard argument of bestsellers being much the same everywhere... is proven to be simply wrong," Wischenbart comments. Europe's bestseller charts are dominated by "a large group of strong authors, from various cultural and linguistic backgrounds". In this elite Stieg Larsson, Carlos Ruiz Zafó*and Henning Mankell count for quite as much as Stephenie Meyer or Dan Brown. The Anglophone blockbuster must share power in Europe. Thus the mass market has edged towards a rough-and-ready European integration. But any such convegence seems less probable for "literary" fiction. The deeper its roots in language, place and culture, the harder in principle for any novel to travel far or well.

So I felt both intrigued and overawed when asked to join a jury to decide on a French prize for a "European novel". In contrast, our own Independent Foreign Fiction Prize operates in a way that De Gaulle might have labelled as typically British: trans-continental, ad hoc, open-ended, without any overarching rubrics or guidelines. It simply tries to find and honour a great overseas novel in a great English translation, whatever its origin. That mission the General himself might deem a historic fit with the "insulaire, maritime" character of an ocean-going mercantile power. Two of the past four Independent victors have indeed arrived from beyond Europe: José Eduardo Agualusa (Angola) and Evelio Rosero (Colombia).

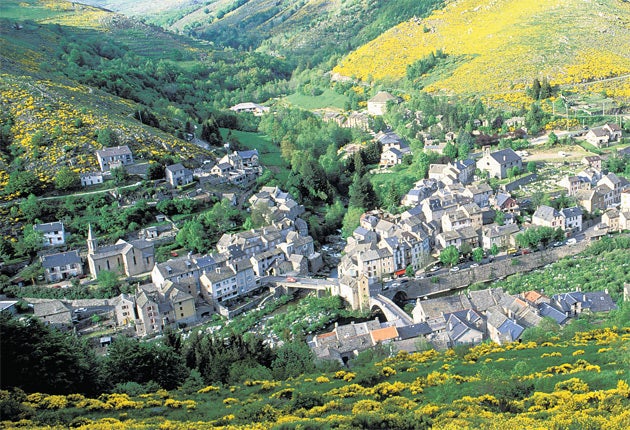

If adjudicating the Prix Cévennes du Roman Européen – now in its fourth year – posed an intellectual challenge, as an experience it could hardly have been more of a treat. With funding from the region as well as European sources, the prize judging and giving takes place in the rolling, wooded foothills of the Cévennes, north-west of Avignon and Nîmes. It's a corner of southern France that has strong British literary connections: Robert Louis Stevenson, attracted by the steadfast Protestant heritage of the Cévenols, set off on his Travels with a Donkey around here in 1878. Recently, at least one Booker and one Orange Prize winner have found second-home boltholes in these hills.

So, in the laid-back surroundings of the Comptoir St-Hilaire – a superbly sited maison d'hôte outside the old coal mining town of Alès – the judges met for a weekend of deliberations amid brisk spring winds last month. A network of French independent bookshops – in locations from Le Havre to Perpignan - had made our job easier by whittling an initial field of 80 novels down to ten. All the contenders had recently appeared in French. In common with the Dublin-based Impac award, translations and books written in the language of the prize headquarters compete on equal terms.

With the genially omniscient novelist, critic and planetary homme de lettres Alberto Manguel as our president, we set to work: Maria Luisa Blanco from Spain, Margot Dijkgraaf from the Netherlands, Pierre-Yves Pétillon from France, Takis Theodoropoulos from Greece and myself. Would unified literary standards in the EU prove easier to define than common yardsticks – or metre rules – for fruit or cheese? First of all, I had my doubts.

Of our ten finalists, two were French translations of English-language books. One of these was a fairly obvious shortlistee: Sebastian Barry's The Secret Scripture, already winner of the Costa and a close contender for the Man Booker. However, our pre-selectors had overlooked the claims of high-profile anglphone authors on the first list - including Will Self, Nadeem Aslam and Tim Parks – and instead opted for a deeply obscure title: Dominic Cooper's Towards the Dawn. Cooper is a Scottish novelist – and definitely nothing to do with the young star of Mamma Mia! and The History Boys - who first released this lyrically melancholic island tale way back in 1976. Yes, it does read very elegantly in French (in English, I have never seen a copy anywhere). Still, I couldn't quite see why it had ever reached the final cut.

Happily, my co-jurors agreed. Most of the other titles we had to assess stood right in the centre (almost too much so) of the European mainstream: among them, Paolo Giordano's The Solitude of Prime Numbers, Henning Mankell's Italian Shoes, Gerbrand Bakker's The Twin, José Saramago's The Elephant's Journey and, from France, Laurent Mauvignier's Des Hommes. Incidentally, this top-selling novel about the emotional aftermath of the Algerian independence war is among many recent works to rebut the outdated British and American belief that navel-gazing French fiction turns its back on recent history.

By and large, our preferences coincided – or, at least, overlapped about as often as you would expect in a jury drawn from a single nation. I was only slightly crestfallen that no other judge shared my fondness for Saramago's 16th-century elephant on his fabulous trip across Europe (the English translation appears early in August).

Still, our criteria began to converge with a good deal more harmony than you ever see these days in Brussels. In the end, we agreed on a clear winner: a book by a young European master of fiction that beyond doubt deserves Pierre-Yves Pétillon's adjective: époustouflant. Call it breathtaking, staggering or (my contribution, not the dictionary's): gob-smacking.

Ruhm by Daniel Kehlmann will reach the UK in September as Fame, in Carol Brown Janeway's translation for Quercus. Already a European (and global) sensation for his comic-but-serious historical adventure Measuring the World, the Vienna-raised, Berlin-based author here comes bang up to date.

Fame takes the form of "a novel in nine stories" which zip wittily, ingeniously, provokingly across places, styles and personalities. Light in their touch, deep in their reach, they dramatise our dependence on the technology that that both brings us close and drives us apart, the role of the imagination in an era of gadgetry, the curse of celebrity and the loneliness of a wired world. Yet the book that bowled us over, of course, was not quite Ruhm or Fame but Gloire, in a brilliantly accomplished French translation by Juliette Aubert.

Last weekend, we returned to the Comptoire St-Hilaire to award Kehlmann the Prix Cévennes. As Margot Dijkgraaf put it in her speech, Ruhm/Gloire/Fame is "an extraordinary novel, one part a satire on our world ruled by telecommunications and one part an ironic commentary on the writer as a star."

If this is a book "full of games and humour, moving and intelligent", it also ranks as one that "in playing with the internet, chatrooms, text messaging, mobile phones and all modern means of communication... illustrates just how easy it is to lose yourself in them." As readers here will soon find out, it may also make it impossible for you ever to read the New Age uplift of Paulo Coelho and his ilk with a straight face again – if, that is, you ever could.

For all Kehlmann's virtuosity, I don't think it entirely a coincidence that this prize went to a novel about people, ideas, cultures in frenzied motion – with all the loss as well as gain that brings. One proper task for a "European" fiction, and its critics, might just be to track and even direct the emotional traffic of a cross-border age. And if that sounds a trifle prétentieux, rest assured that Kehlmann never is. On Saturday, amid the butterfly-filled meadows of the Cévennes – light years, it felt, from the 24/7 data-blitz of his novel – this superstar of modern German prose told me that he has just fallen in love with the work of a writer seldom linked to the Continental avant-garde: Alan Bennett. In all the visions of a common European home nurtured by Monnet, De Gaulle and the other history boys, I'm not sure that a Leeds-Berlin literary axis ever crossed their mind.

'Fame' by Daniel Kehlmann, translated by Carol Brown Janeway, will be published by Quercus on 2 September

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments