Edith Wharton: Battle to save The Mount

The home of America's first lady of letters, Edith Wharton's estate is a site of national importance. But now its proprietors face the same fate as so many other homeowners – foreclosure. David Usborne reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

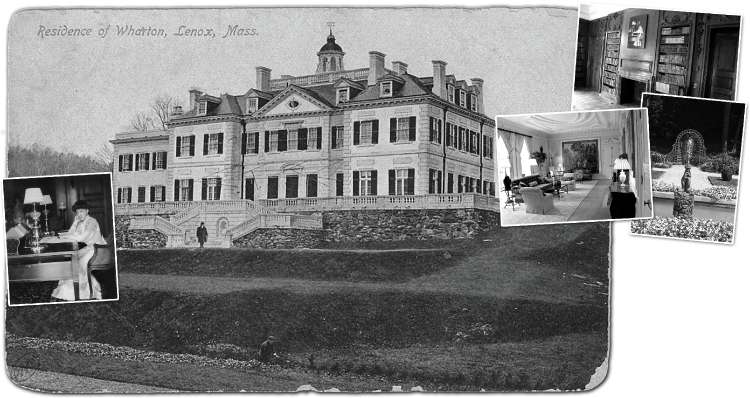

Your support makes all the difference.Take the gravel drive into The Mount, the estate that once belonged to the early 20th-century novelist Edith Wharton in the rolling Berkshires of western Massachusetts, and the first structure you see is a charming but crumbling stable block.

A vinyl banner strung across it proclaims: "Future Restoration Project."

Such vigorous optimism would have been appreciated by Ms Wharton, whose novels exploring New York society in the Gilded Age included The Age of Innocence, partly written in the grand white stucco house that awaits you around the next corner, and The House of Mirth. Yet, it may be misplaced, for all is not quite well at The Mount.

Indeed, there were moments this spring when it seemed that the estate, after its winter hibernation, might not have reopened this summer at all. After several years of major renovation work, which included stabilising the main house which until a few years ago was close to falling down, and replanting the gardens according to Ms Wharton's own design, the trust that runs it has hit the financial buffers.

Worse, because of debts amounting to about $9m (£4.6m), it finds itself facing a fate familiar to thousands in Main Street America in these days of tightened credit – foreclosure by the bank that holds its main mortgage. Staving off that day has become the trust's first priority with the launch in recent weeks of a fundraising drive. Whether it can succeed remains to be seen.

Foreclosure would mean the property being sold at auction, most likely to a private buyer. It is a prospect that even the most casual of Wharton fans would recoil at. It remains the only one of her former homes that is open to the public and stands as a physical monument to her achievements, which included not just her fiction writing for which she won a Pulitzer Prize but also her humanitarian work with refugees in France during the First World War and her passion for home and garden design.

Rarely mentioned in literary lessons, one of Wharton first efforts was a book on interiors. Published in 1897, The Decoration of Houses is still in print. It is no surprise therefore that she involved herself intimately with the layout of The Mount, which was completed in 1902, as well as the planting of its formal gardens. Inspired by Belton House in Lincolnshire, the house is an expression of her preoccupation with simple comforts and symmetry.

"The truth is that I am in love with the place, climate, scenery, life and all," she once wrote. Wharton and her husband Teddy maintained a principle home in New York. During summer and spring sojourns at The Mount, her routine typically included writing in bed – the scribbled pages were dropped to the floor of her bedroom and left for her secretary to type up – and then entertaining guests, most notable among whom was Henry James.

It was in one of her many short stories, The Fulness of Life, that Wharton wrote that a woman's life is like "a great house full of rooms", most of which remain beyond public view, "and in the innermost room, the holy of holies, the soul sits alone and waits for a footstep that never comes". Plumbing as far as Wharton's soul may be too much to expect, but a visit to her house offers a window on a time in her life that included periods of great happiness and productivity as well as distress. When she finally departed for Europe in 1913 and settling in France her marriage had foundered. It was while she was crossing the Atlantic that Teddy cabled her saying he had sold the house.

"The Mount is a living symbol of her," said Christopher Tugendhat, whose own library includes a full set of Wharton first editions. A member of the House of Lords but an occasional visitor to the Berkshires, he became an interim trustee of The Mount in 2006 shortly after the previous board resigned en masse and is closely involved saving it from foreclosure. "She not only wrote some of her best-known books there but it was in a sense probably where she was happiest until the breakdown of her marriage," he added.

Other literary experts are also rallying to the cause. "Everyone who lives in Wharton's true home – the Republic of Letters – must join the effort," Sharon Shaloo, executive director of the Massachusetts Center for the Book, wrote in a letter to The New York Times. "The Mount belongs to everyone who cares about literary achievement, architectural and landscape design, and women's place in our national history."

No one has had a more harrowing few weeks than Susan Wissler, chief operating officer at The Mount. She laid off all her staff, including maintenance workers, tour guides, gardeners and a gift shop team, then called them back when a 30-day extension on a first foreclosure deadline was offered by the Berkshire Bank and the new season seemed viable again. "We took something of a chance opening," she admitted sheepishly.

On a recent spring afternoon, she showed a visitor through the house with the affection of a parent presenting a child. No facet of Wharton's jewel went un-noted, from the grotto-like entrance hall to the sophisticated bathroom plumbing upstairs and the way furniture is arranged in the main reception room to allow conversations to blossom in different corners. Our tour finished on the tin roof where an area of crumbling stucco on a chimney stack that needs attention elicits a sigh. "The issue is that the more you restore the house the more it costs to maintain," she said.

First sold to another family, The Mount was then an extension of a nearby private girls' school for nearly 40 years until 1976. Acquired by the trust four years later, it was then serving as the base of a Shakespeare theatre company whose occupation only hastened the dilapidation. The actors finally gone, serious restoration with a few to public visitation began in 1998. It has already absorbed more than $13m and the main house it is not yet finished with flaking walls and cracking ceilings upstairs.

When the new board arrived 18 months ago, the cash crisis was brewing but not fully in view. "I hadn't realised what a difficult state we were heading into," said Lord Tugendhat.

After the money finally dried up this winter and it became impossible to service interest payments on its mortgage, some blamed a decision in 2006 to purchase a large portion of Wharton's own trove of books from a collector in England. About 1,100 of those volumes now occupy shelves in the house's library and there are as many if not more in storage in the attic. The cost, however, was huge – $2.5m – and, indeed, the collector has still not been paid a portion of his money. (And because of the exchange rate, the outstanding sum of £450,000 continues to swell when converted into dollars.) Whether or not too much money has been spent, The Mount's greatest failing has been in the all-American art of fundraising. They just haven't been very good at it. A ploy to attract money by attaching the names of donors to individual books in the library, for instance, fell flat.

For now, at least, imminent disaster seems to have been averted. In March, The Mount went public with its plight with an appeal for funds on its website and in the media. It is currently striving to raise $3m, which will become $6m because of a pledge by an anonymous donor to match that sum. As of a few days ago slightly less than $1m had been cornered.

Among those writing cheques has been Michael Eisner, the former chairman of Disney, who donated $25,000. Meanwhile the Berkshire Bank first extended its foreclosure date by 30 days until 31 May. Now it has gone further by giving the Mount until November to come up with its missing payments.

"It gives us room," said a relieved Gordon Travers, another trustee and the man doing most of the negotiating with the bank. "It gives us a window of time to not only raise money but to do so in the context of The Mount being open for the season, which was not something we are all that optimistic about when the music stopped." He is talking about February and March when there simply nothing in the pot.

"In the beginning it was like those POW movies during the Second World War where they were always trying to tunnel out using spoons and things like that. Well, at the start we were digging with tea spoons and we have graduated now to soup spoons. So I guess we are least moving up the spoon food chain. Right now we are all fairly confident that we will make it to £3m by the end of October."

Plugging the immediate funding gap will only do so much. The greater goal is to establish a permanent endowment running to as much as $25m, if they can find a way to tap local and New York philanthropists for a good deal more money than has been forthcoming so far. Then The Mount could become more than just a shrine to Wharton the literary giant but something more.

"She was one of the great novelists of the first part of the 20th century," said Lord Tugendhat. "But second, she was one of the most important women in the same era with the extraordinary work she did with refugees in the First World War, which now is very topical. I think The Mount can be made into a centre studying the whole span of her contributions."

This is the laudable long-term vision of everyone at the Mount, one which includes not just finishing repairs on the main house but fixing up the stable block and opening it for seminars and courses. But while they are still armed with nothing but soup-spoons it remains a still fragile dream.

Edith Wharton - a life in books

Described as one of America's greatest writers and literary wits, Wharton's talent lay in her ability to evoke the scandalous and sheltered lives of New York society's powerful elite.

The House of Mirth (1905), the first of many chronicles of an age of manners and money, brought her fame and established her as a literary icon. The best-seller follows the life and tragic death of a pleasure-seeking Manhattan socialite beginning with her quest to secure a worthy husband and ending with her fall from grace and social ruination.

Wharton's most known work, The Age of Innocence (1920), won the 1921 Pulitzer Prize making her the first woman to win the award. It is a meditation on her young life as a member of the exclusive Fifth Avenue set. She said the novel was an apology for The House of Mirth and its harsh social critique.

Her prolific output – in her 75 years, she published 38 books – culminated in her autobiography, A Backward Glance (1934), and the unfinished The Buccaneers (1938). Although born in New York, she spent most of her life abroad and, following her divorce, settled in Paris in a deliberate break with America and her past.

Claire Ellicott

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments