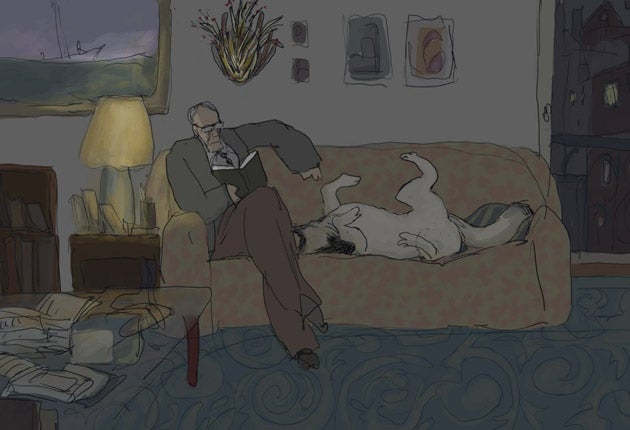

Dramatic Paws: J R Ackerley

J R Ackerley's relationship with his dog made great literature, and now there's a film version. Peter Parker picks up the scent

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.JR Ackerley's My Dog Tulip is surely one of the least likely books to have been reissued with the words "Now a major motion picture" on its jacket.

Published in 1956, this unusual memoir describes Ackerley's relationship with his neurotic and highly possessive alsatian bitch, who in real life was named Queenie. A long-standing literary provocateur, Ackerley was determined to emphasise Queenie's animal nature and so wrote, in unabashed detail, not only about his dog joyously breasting the bracken in pursuit of rabbits on Putney Heath but also about his farcical attempts to get her mated, and her excretory habits (to which he devoted an entire chapter). Several of his admirers were appalled, but while Edith Sitwell dismissed the book as "meaningless filth about a dog", others, including E M Forster, Christ-opher Isherwood, Truman Capote and Julian Huxley, recognised that, like everything else Ackerley produced, the book was both seriously intended and beautifully written.

Paul and Sandra Fierlinger, a husband-and-wife team based in Phila-delphia, have now brought My Dog Tulip to the screen as an animated feature (out on Friday), with voices provided by Christopher Plummer, Lynne Redgrave, Isabella Rossellini and several incessantly barking canines. Vanity Fair has described the film as "the love story of the year", and Ackerley himself admitted that he found Queenie more satisfactory than earlier and more conventional partners. "She offered me what I had never found in my sexual life," he wrote. "Constant, single-hearted, incorruptible, uncritical devotion."

This had certainly been lacking among the procession of waiters, actors, sailors, guardsmen, delivery boys, petty criminals and policemen who trooped through his life, some of them barely pausing to tidy the bed. His search in such company for the fleeting figure he designated "the Ideal Friend" was doomed. As his close and frequently exasperated friend E M Forster observed: "Joe, you must give up looking for gold in coal mines ... it merely prevents you from getting amusement out of a nice piece of coal."

Ackerley described his endeavours in his outstanding memoir My Father and Myself (1968), in which he devoted as much attention to the details of his own sexual needs as he had to those of his dog in the earlier book. Ackerley's father, an ebullient and extravagant figure known popularly as "the Banana King", was the co-founder of Elders & Fyffes, the fruit importers; his mother a former actress. Ackerley was the second of three children, all born out of wedlock, and he subsequently discovered that his father had another, secret family consisting of a mistress and three daughters. As a consequence, Ackerley inherited little more than financial chaos when his father died in 1929 and thereafter was always short of money. As well as Queenie, he ended up sharing his cramped Putney flat with his divorced, mentally unstable sister and their ancient and incontinent Aunt Bunny, a former operetta singer. He later discovered that, as a young guardsman, his father had been bought out of the Army by a male admirer and subsequently kept by a Swiss-American Count of the Holy Roman Empire.

Given such material, it is unsurprising that Ackerley's writings were largely based on his own life. Having been wounded and taken prisoner, he spent the last year of the First World War in internment in Switzerland. He drew upon his experiences there, and in particular upon his hopeless devotion to a young airman, to write The Prisoners of War (1925), one of the first British plays to put homosexuality squarely and unapologetically on the stage. His travel book Hindoo Holiday (1932), based on the five months he spent in India as secretary to the Maharajah of Chhatarpur, was similarly forthright about his and His Highness's sexual proclivities.

No less recklessly candid was his only novel, We Think the World of You (1960), a lightly fictionalised and grimly funny account of acquiring Queenie from a married, long-term lover who was serving nine months for burglary. Ackerley cheerfully described the book as "Homosexuality and bestiality mixed, and largely recorded in dialogue: the figure of Freud suspended gleefully above". Friends worried that he would be prosecuted, but instead he won the WHS Smith Literary Award, presented by a bemused Lord Longford.

Ackerley was, for almost a quarter of a century, the literary editor of The Listener, the BBC's weekly magazine which ran from 1929 to 1991. When he took over the post in 1935, he became responsible for the eight pages per issue "allocated to art, poetry, books and literature". He persuaded many of the leading writers of the time to become regular contributors: Forster, Leonard and Virginia Woolf, Clive Bell, Wyndham Lewis, Kenneth Clark, Maynard Keynes, Geoffrey Grigson, Cecil Day Lewis, Louis MacNeice, W H Auden and Isherwood. Anthony Howard described him as "by common consent the greatest literary editor of his time – perhaps of all time".

The hidebound BBC provided another arena for Ackerley to conduct his guerrilla campaign against conventional moral values, and he spent much of his time attempting to smuggle politically or sexually "difficult" material into the magazine. "I think that people ought to be upset," he once wrote, "and if I had a paper I would upset them all the time ... life is so important and, in its workings, so upsetting that nobody should be spared".

Ackerley upheld this invigorating creed throughout his life. He was a true libertarian, who believed that life for dogs and humans alike should be lived off the leash. In retirement, he continued to argue in favour of both gay and animal rights. He died in 1967, a month before homosexuality was legalised in Britain – an irony he would have been the first to appreciate.

Peter Parker's biography of Ackerley is published by Constable

'My Dog Tulip' by J R Ackerley, New York Review of Books Classics £8.99

"Upon the flattened grass beneath the tombstones in summer-time I occasionally find coins, which, unnoticed in the darkness, have slipped out of trouser pockets, and other indications that the poor fleeting living, who have nowhere of their own, have been there to make love among the dead. To what better use could such a place be put? And are not its ghosts gladdened that so beautiful a young creature as Tulip should come here for her needs, whatever they may be?"

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments