Business Adventures by John Brookes: A Bible for billionaires

Warren Buffett and Bill Gates are big fans of an out of print 1960s business book. Seth Stevenson thinks he knows why

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

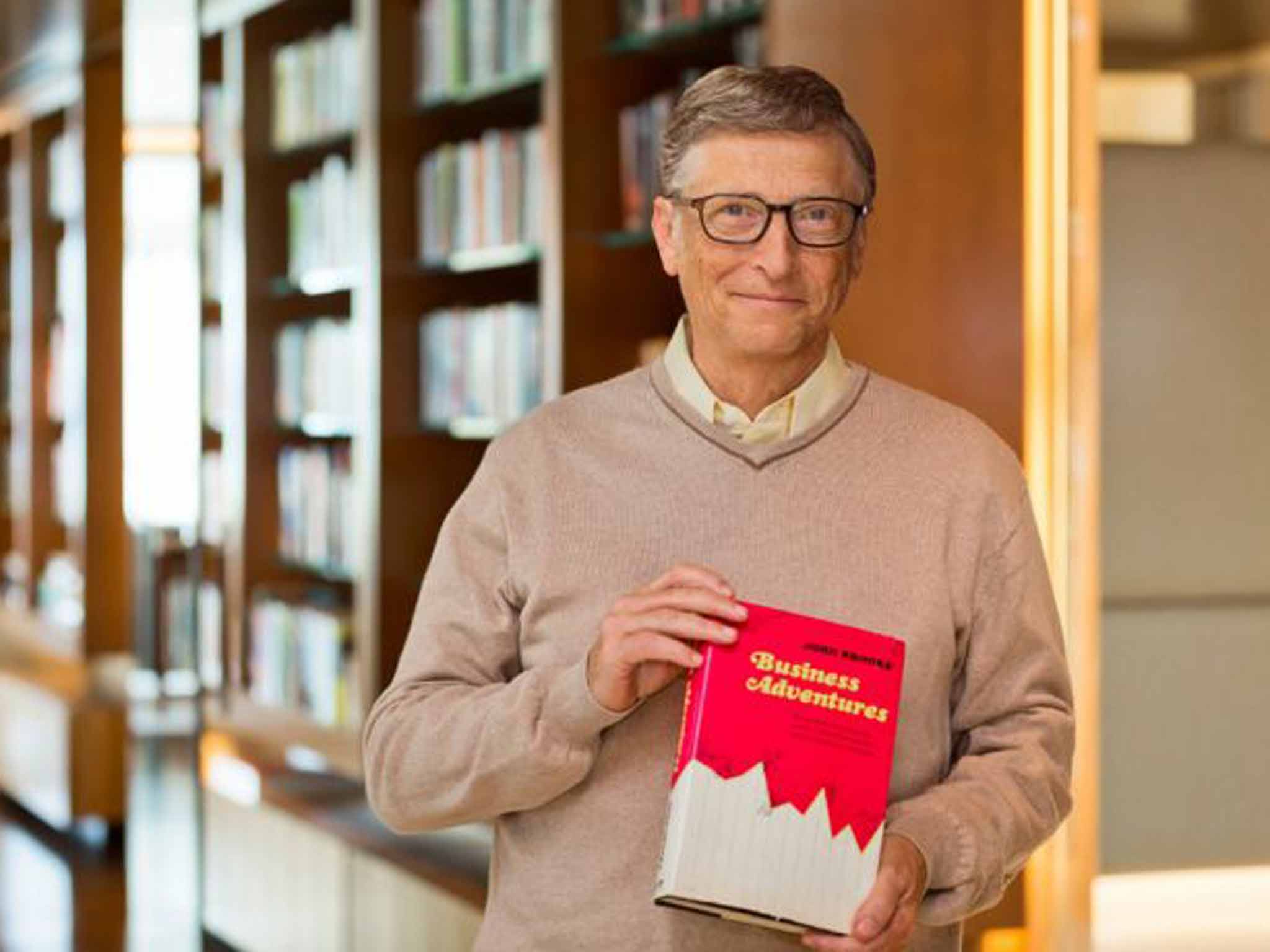

It has recently emerged that America's two richest men share not only a fondness for bridge, but identical taste in literature. Both Bill Gates and Warren Buffett – according to an essay this week from Gates – count Business Adventures by John Brookes as their single favourite book about business. Why is this compendium of 1960s New Yorker articles catnip for billionaires?

1. The prose is superb: reading Brooks is a supreme pleasure. His writing turns eye-glazing topics (eg, price-fixing scandals in the electronics market) into rollicking narratives. He's also funny. In a piece about the spectacular failure of the Ford Edsel, Brooks describes the car's elaborate grille as "the charwoman trying on the duchess' necklace". Noting that an Edsel was stolen three days after its debut, he writes, "It can reasonably be argued that the crime marked the high-water mark of public acceptance of the Edsel; only a few months later, any but the least fastidious of car thieves might not have bothered."

Brooks wields a sharp dagger from a detached, chuckling remove – as when he writes that Clarence Saunders, the founder of the Piggly Wiggly supermarket chain, had "a gift, of which he may or may not have been aware, for comedy," or when he notes that Saunders "in his teens was employed by the local grocer at the pittance that is orthodox for future tycoons taking on their first jobs".

You know who sounds like Brooks? Warren Buffett. Classic homespun Buffett-isms such as "you only find out who is swimming naked when the tide goes out" and "I try to buy stock in businesses that are so wonderful that an idiot can run them, because sooner or later, one will," fit right in alongside Brooks' wry turns of phrase. It comes as no shock that Buffett loves this book, and it would likewise be no surprise if he'd consciously modelled his writing on it.

2. The reporting is nuanced: as Gates notes, Brooks eschews "listicles" and doesn't "boil his work down into how-to lessons or simplistic explanations for success". Instead, he tells entertaining stories with richly drawn characters, set during heightened moments within the world of commerce. He invites the readers to draw their own conclusions about best practices. After reading these pieces, you can't help but see that businesses don't rise or plummet based on trendy strategies, advanced research or silly employee perks. Their fortunes are determined by small groups of humans – full of flaws and foibles – who come together, make decisions under pressure, and fail or succeed to create something larger than the sum of their parts.

3. The lessons still apply: when Brooks writes about the Edsel, he could easily be reporting on a disastrous consumer product launch that happened last week, with the attendant finger-pointing at marketing mishaps and engineering snafus. When he recounts an inexplicable three-day panic that occurred on Wall Street in 1962, he might as well be talking about the mysterious "Flash Crash" of 2010. When he writes about income tax flaws he could be filing a dispatch from any moment in the past century.

Perhaps the eeriest and most edifying piece from a modern-day perspective is Brooks' look inside Xerox during a moment of transition. Consider: in the mid-1950s, Americans made about 20 million photocopies annually, using bad technology that produced worse results. By 1964, after Xerox introduced xerography – a proprietary process that let copies be made on regular paper and with great velocity – that climbed to 9.5 billion. Two years later, it was 14 billion. Xerography was a technological revolution that some put on par with the wheel. Brooks describes a burgeoning "mania" for copying – "a feeling that nothing can be of importance unless it is copied, or is a copy itself".

The arrival of xerography spurred hopes and fears not unlike those stirred up in the early days of the World Wide Web. It turned office culture on its head and changed the nature of text propagation more than anything since the days of Gutenberg. As for Xerox the company, it was generating so much profit that it seemed as though its copier drums were spitting out hard currency. When Brooks pays a visit to the corporate campus in New York, he finds the executives' biggest concerns revolve around Xerox's charitable support for the United Nations.

Then, as now, disruption begat adaptation. Copying grew commonplace. Xerox ploughed its revenue into R&D in a search for the next hit, but never managed to translate its breakthroughs into best-selling products.

Bill Gates calls the Xerox piece one of Brooks' "most instructive stories". It's easy to see why the former Microsoft CEO might consider this the most poignant of tales among the many poignant tales that populate Business Adventures. In Xerox, we see a corporate behemoth with a single, killer product; a desperate, but mostly ineffective, effort to find something else that gets traction in the marketplace; and an embarrassment of riches that are nobly redirected towards global betterment.

As reports emerged that Microsoft will lay off up to 18,000 employees, and the Gates Foundation continued its quest to craft a better female condom, I couldn't help but wonder: was Gates dipping into his dog-eared copy of Business Adventures yet one more time? And if he did, would it be for wisdom or for succour?

© Slate

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments