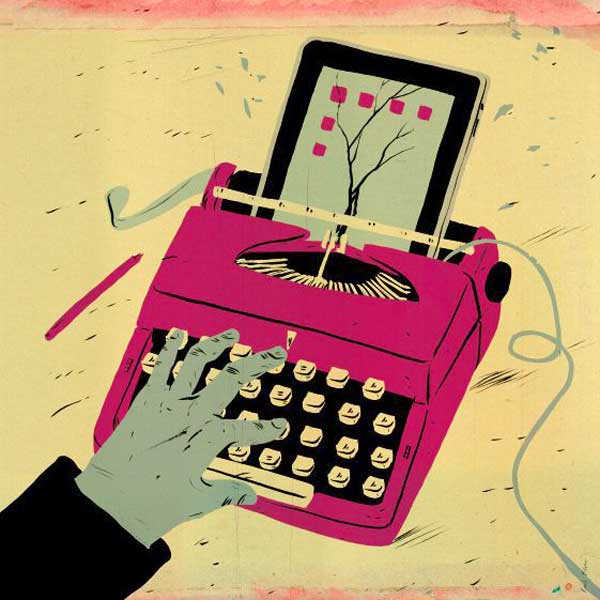

Brave new world: Writers will have to change their attitude if they’re to catch up with the videogames industry

Digital media offer unbounded opportunities for writers to experiment with form and conventions. So why do so many still allow themselves to be imprisoned by the traditional codex format of the book, asks Joy Lo Dico

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Last month, for the first time, The Bookseller trade magazine's annual forward-gazing FutureBook conference was sold out. The previous year, only 150 people from the world of publishing, writing and technology had gathered to lecture and gossip about where the book goes next. Last month, 400 crammed the halls. Publishers, it seems, have finally clicked when it comes to the digital world. But where are all the writers?

Kate Pullinger used to be a regular key speaker at such meetings. An acclaimed author in the traditional, codex format of books, Pullinger is currently longlisted for the Impac Dublin Literary Award and the winner of the Canadian Governor General's Award for Fiction for her book The Mistress of Nothing, the story a Victorian lady and her maid who set sail down the Nile. She has mastered the codex form, with six novels to her name, but over the past 10 years she has also been pushing the boundaries of digital fiction. "But I haven't been to many conferences in the past three years," she tells me. "I was almost always the only writer there, and I got tired of that."

In the past year, publishers have leapt at the chance of finding ways to make the digital book work. Taking advantage of the interactivity of platforms such as e-readers, iPads and smartphones, they have found considerable success with non-fiction. Jamie Oliver's "20 Minute Meals" has been a chart-topper among the apps. Stephen Fry released a version of his autobiography as an app, "MyFry", for the iPhone, which invites users to scroll around a dial to access different segments of his life. Another runaway success has been "The Elements" by Theodore Gray, a science book that was adapted for the iPad and provides in-depth descriptions and images of every element in the periodic table. Since Touch Press launched it in digital form in April, it has sold 160,000 copies and generated $2m in revenue.

But fiction has not found the transition to anything other than the e-book format so easy. "Fiction seems not to be grasping the potential," says Pullinger. "Many of the apps and enhanced e-books are just codex books with videos and notes shovelled in – like DVDs with their added extras."

Pullinger started working in online fiction with the TrAce Online Writing Centre, based at Nottingham Trent University, a decade ago. "I was asked to teach online creative-story writing," she says. "Back in 2001, this was new to me. I only really used the internet for booking flights and sending emails. But after teaching the course, I found that it's a useful environment for focusing on the text, and that I had a kind of affinity for it."

Since then she has been experimenting, often in collaboration with the electronic artist Chris Joseph, on several major projects. "Inanimate Alice", which came out in 2005, is a sequence of stories about a young girl who exists between real and digital worlds. The written narrative is deliberately minimalist and built into a rich audio-visual experience. Then came "Flight Paths", begun in 2007, which Pullinger describes as a "networked novel". It was inspired by the news story of an illegal immigrant who had stowed away behind the landing wheel of an aircraft, only to fall to Earth in suburban London. In addition to her own resulting short story, Pullinger invited others to contribute their own takes on the theme. "The third phase of 'Flight Paths' is now about to come together in digital and print," says Pullinger. "The first phases were open to discussion; the third is about closing it."

Her most recent project, "Lifelines" – autobiographies of young people around the world put into historical and geographical contexts – has been specifically made as an educational tool.

Pullinger and Joseph have delivered stylish advances to the world of digital fiction, but they still exist in a rarefied atmosphere. What hasn't come along yet is a proper commercial success in the medium. Pullinger puts that down to two hindrances.

The first of these is that publishing houses lack the drive to fund and develop new online writing and, as a result, most experimentation happens either in groups or at universities. Poole Literary Festival, in partnership with Bournemouth University, held the first New Media Writing Prize this year; Leicester's De Montfort University's creative writing department, in which Pullinger teaches, produced three of the shortlisted authors for that award.

The second hindrance is the reading public's love affair with the book. "The codex book is a kind of prison," says Pullinger. "It is such a dominant idea in our culture, such a beloved thing that we replicated it digitally as an e-book, even though we could and can let it change and evolve."

So what happens next? Will fiction ever break out of the codex prison? Salman Rushdie, talking recently to the online interview site Big Think about his latest book, Luka and the Fire of Life, written for children, seems to have realised that there's more to fiction than the book. He was watching his son play the videogame Red Dead Redemption, from Rockstar Games, the makers of Grand Theft Auto, and became entranced by the daunting possibilities of multiple narratives.

Rushdie is not the first to have spotted that it is the games industry, rather than publishers, that is making the greatest strides in creating digital fiction anew – albeit on its own terms and often with guns involved. Max Whitby is the founder of Touch Press, which made "The Elements", and brought out Marcus Chown's equally non-violent "The Solar System" with Faber, again for the iPad, late last year. He eagerly references Red Dead Redemption. So, too, does Pullinger, who has watched her teenage son play the game.

"Not all games are that clever, or good for you," says Pullinger. "But what is amazing about them, when they work, is the story worlds that they create. It has echoes in TV, in the novelistic long-form series such as The Wire or The Sopranos. Those kind of literary forms are having a profound effect on their culture."

What does seem to be in consensus is that technology, in particular the iPad, has finally provided a platform that could change the world of fiction. Now all the publishers need is that elusive digital bestseller.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments