Boyd Tonkin: Barry Unsworth made past and present talk. Does his art have a future?

The Week in Books

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.I always thought it apt that Barry Unsworth lived just over the hill from Lake Trasimeno. That gorgeous corner of Umbria once witnessed (in 217BC) the slaughter of the legions in their tens of thousands as Hannibal marched on Rome. Somehow a novelist worth the name has to encompass both the beauty and the carnage. Walter Benjamin's dictum seems to fit so much of Unsworth's work: "There is no document of civilisation which is not at the same time a document of barbarism."

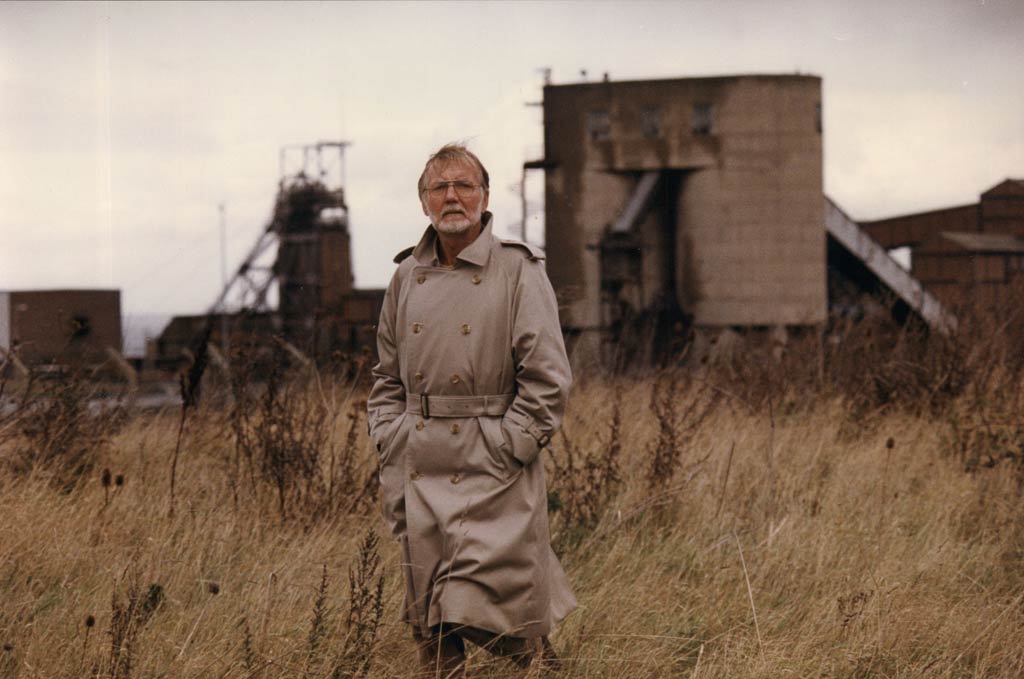

The most skilful, sensitive and versatile of our historical novelists, the County Durham miner's son has died aged 81. I remember a golden day spent at his house outside Perugia, at the start of September and just after he and his Finnish wife Aira, a translator, had picked the figs from their sloping acres. I had come to interview him about The Ruby in her Navel – a superbly polished novel that, as always, yoked the near and the far: in this case, the short-lived multi-faith tolerance of the 12th-century Norman kingdom of Sicily and our own fragile hopes for the survival of mutual respect in an era of strutting dogmatism.

We sat on the terrace, looking out over the valley below. He explained how his tenure in this corner of an Italian Eden had come at the cost of long, tense negotiations with the neighbours – see the barbed comedy of his After Hannibal. For a while, the hunters used to trample his fences, until he got to know a local notable whose word brooked no dissent. Even Eden has its law-makers, and its law-breakers. It was one of those days when work felt not just like a pleasure, but something much rarer: a blessing.

The success of Sacred Hunger, his intimate epic of the Atlantic slave trade that jointly won the Booker Prize in 1992, had allowed him to move to Umbria. In the literary world, virtue does not often lead so directly to reward. That novel, like his earlier, Liverpool-based Sugar and Rum, had made slavery not just an African but an indelibly British story. He returned to the subject with his final novel, The Quality of Mercy. It moved the story of the mutinous slave ship on a generation, and dramatised the way in which the capital amassed from overseas cruelties helped to kick-start the Industrial Revolution back in Britain.

Unsworth always wrote quite beautifully, but often about harrowing themes. Splendour and suffering coalesce, separate strata of a single narrative, like the scenes of toiling pitmen in the darkness below a cultivated nobleman's estate that close The Quality of Mercy. This conjunction of sun and shadow had marked his fiction from the first. His early stints as a teacher in the Mediterranean fed richly imagined narratives of the Greek and Turkish past, of bitter enmity in lovely locations, such as Mooncranker's Gift and Pascali's Island. Even the most glorious history is soaked in ambition, violence and deceit. It was a perspective made graphically clear in his suspenseful novel about archaeologists and oil prospectors in the future Iraq, Land of Marvels. The lands of marvels are also lands of mayhem.

This visionary of past times deserves a historical context of his own. Social mobility (his father had left the pit for an office job), wider access to higher education (he won a place at Oxford, but chose Manchester), new chances to travel and work abroad, a publishing industry that valued high quality: Unsworth shone thanks to the brighter side of postwar British culture. Come the 2050s, will critics look back fondly over any faintly similar career? Just now, that sort of continuity of achievement looks doomed. But we can never map the future from the present. For now, a collected edition of Unsworth's fiction – in every format – would help to keep the past thrillingly alive.

When tardy publishers set a spanking pace

One of the reasons why many publishers will go extinct is the medieval absurdity of their pretence that 12 or 18 months must elapse between receipt of a manuscript and its release. Bunkum. Even in traditional editions, you can print, bind and distribute within a couple of weeks if you really want. And it has taken the erotica boom – itself prompted by the digital success of EL James's mild SM scenarios – to expose this dirty secret yet again. Fifty Shades of Grey rip-offs already fill groaning shelves, with more to come. Most, I fear, will be a real punishment to read. Could not Penguin raise the bar for female-friendly sauce with a reprint of the truly sultry stories of Anaïs (Delta of Venus) Nin?

A true examination for All Souls

What is the point of All Souls College? Many observers have asked that question of the venerable fellows-only Oxford institution, with its cushy sinecures fought over in competitive exams known for the teasing eccentricity of their papers and laconic essay topics, such as "chaos"; "error" and "charity".

As far as charity goes, the rich endowments of All Souls include the freehold of Kensal Rise Library, the branch shamefully shut, stripped and plundered at dead of night (down to the plaque that marked its opening by Mark Twain in 1900) by the most grossly philistine Labour council in Britain: Brent.

Although the municipal hooligans of Brent handed the keys back to All Souls, the Friends of Kensal Rise Library have now requested that the college transfer the freehold to them, under the Charities Act 2011, to enable the building's renewed use as a library.

All Souls should comply, prove its lavish assets serve a greater purpose than the upkeep of a favoured few, and do its bit towards mitigating the chaos and error that Brent has sown.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments