Books of the Year: Literary fiction

Howard Jacobson richly deserved his Booker prize, but so many other novels divided cultured opinion

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.At the back of Douglas Coupland's latest novel, Player One (William Heinemann, £16.99), there is a glossary of made-up modern vocabulary which doesn't, but easily could, include the term "The Coupland Perception Incomprehensibility Paradox": the increasingly frustrating realisation that well-read people whom one cares about and respects quite frequently nurture opinions about literature which are inexplicably contrary to one's own.

The longer I work in books journalism, the more bizarre I find it that many of the people I most love and admire have completely different literary favourites from mine. I can no more comprehend how my nearest and dearest don't like Coupland's books than I can get my head around some of my friends being Tories. His latest work of genius, published in October, is set in an airport hotel bar and has half-a-dozen modern misfits telling their life stories around an oil-price-driven apocalypse and toxic snow: it ticks every Couplandesque box, for fans; those who don't get on with his fiction will hate it... but I still like you anyway.

Nor do I always agree with the reviews that appear on these pages. The writer who reviewed Jonathan Franzen's long-awaited Freedom (Fourth Estate, £20) here asked for an extra week to come back down to earth after reading it. Yet I read this story of smug, selfish, liberal Americans - all 570 pages of it - anxiously waiting to start caring about Walter and Patty Berglund and their annoying children. I'm afraid it didn't happen, and for me the book was not worth waiting nine years for after Franzen's wonderful The Corrections.

Speaking of long waits, I did, to my relief, wholeheartedly agree with the Man Booker Prize jury's decision finally to honour Howard Jacobson for his tender, funny 11th novel, The Finkler Question (Bloomsbury, £18.99). A touching and sardonic analysis of maleness, Jewishness, friendship and grief, this short novel has more warmth and wit than any number of doorstop-writing contemporaries who are effortfully trying to squeeze out the Great American Novel.

There were some memorable novels on the Booker shortlist, too. Leaving aside the well-deserved inclusion of Peter Carey's Parrot and Olivier in America (Faber, £18.99) and the perhaps inevitable overlooking of Martin Amis's The Pregnant Widow (Cape, £18.99) and Ian McEwan's Solar (Cape, £18.99), Andrew Levy's The Long Song (Headline Review, £18.99) tells the turbulent story of the last days of slavery through the unreliable testimony of Miss July, looking back on the period as an "old-old woman". She is not a likeable character, exactly, but she's a hard one to forget, and her peevish, mischievous tone of voice is an authorial triumph.

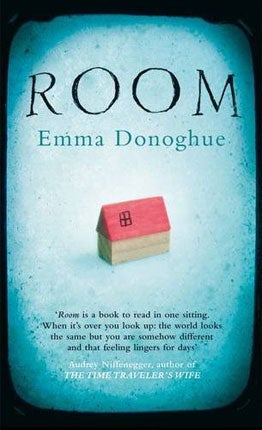

So, too, is Emma Donoghue's desperately affecting seventh novel, Room (Picador, £12.99). Though inspired by the horrific real-life story of Elizabeth Fritzl, it achieves its aim of portraying the pedestrian claustrophobia of any ordinary mother-child relationship. Five-year-old Jack is locked in a small, furnished cell with his mother, born from the rapes she suffers nightly by her kidnapper, their jailor, "Old Nick". Their escape and Jack's subsequent exposure to the terrifying world outside could have been a disaster in the hands of a less intelligent writer, but Donoghue's creations live on in the mind.

If the Booker shortlist could have only one globally sprawling novel, I would have preferred Barbara Kingsolver's dazzling, Orange Prize-winning The Lacuna (Faber, £18.99) to Damon Galgut's In a Strange Room (Atlantic, £15.99), and my favourite novel of the year that starts with a character named Serge, silkworms and a child's near-drowning was Rose Tremain's creepily affecting Trespass (Chatto, £17.99) and not Tom McCarthy's allegedly "experimental", Booker-shortlisted C (Cape, £16.99). "[C] certainly rejects the default mode dominating mainstream fiction and most culture in general: this kind of sentimental humanism," McCarthy has said about it. "If you don't kowtow to that you're going to upset a few people." Hmm.

Likewise, why no Helen Dunmore's extraordinary The Betrayal (Fig Tree, £18.99) on the shortlist? In the sequel to 2001's brilliant The Siege, Dunmore makes palpable the fear and paranoia suffered by ordinary citizens of Stalin's Russia. Young Anna, her husband Andrei and younger brother Kolya have barely survived the cold and starvation they suffered in The Siege when they are swept up in the 1952 Doctors' Plot. Dunmore is at her very best, making the unimaginable hideously real.

Dunmore is an old hand, but here are two newcomers to look out for. Ned Beauman, the debut author of Boxer, Beetle (Sceptre, £12.99), has shown that he can do linguistic pyrotechnics and a warped sense of humour; while the newby publisher Peirene aims to bring translated short fiction to an English-speaking audience, sometimes years after it has caused a splash in its first incarnation. Maria Barbal's sparse and haunting Stone in a Landslide (£8.99) was a promising start.

But to end on a bone of contention, what travesty caused David Mitchell's stunning The Thousand Autumns of Jacob de Zoet (Sceptre, £18.99) not to win every literary prize in Britain? This dense, kaleidoscopic novel, set in a Dutch trading post in 1799 Japan, shows a great writer at the top of his game. Jacob de Zoet is my novel of the year, and Mitchell (above) my author of the decade. Yet the estimable critic Philip Hensher called it "an exotically situated romance of astounding vulgarity". It's an infuriating example of the Coupland Paradox in action.

Katy Guest is the literary editor of 'The Independent on Sunday'

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments