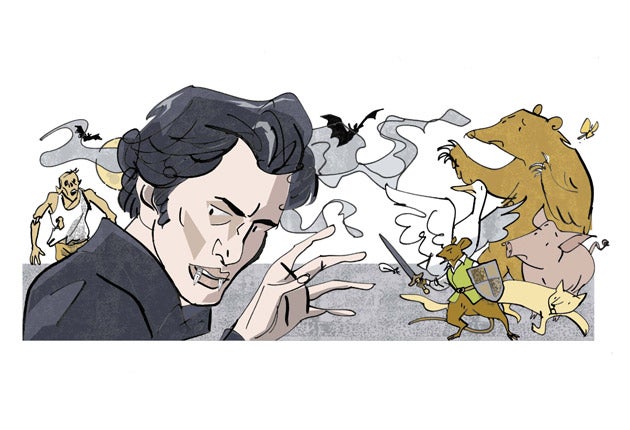

Bedtime stories to disturb your sleep

Traditional fantasy for children is proving less and less popular. Inbali Iserles reports on the latest undead trends

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Is paranormal romance sucking the blood out of the children's book market?

Nostalgic parents who have observed their children's holiday reading this half-term would be forgiven for thinking so – and the figures suggest that they'd be right. Vampires and their demonic counterparts accounted for a quarter of the top-20 fiction sales for children, and 18 out of 20 for young adults in January 2011, according to The Bookseller. And adult readers and writers who remember more innocent-seeming days of Redwall otters and sheep-pigs are, if you'll excuse the pun, bored stiff with the undead trend.

"[The new horror is] the worst kind of Mills & Boon stuff," says Mary Hoffman, the author of the bestselling Stravaganza series. "Especially when it takes the form of disguised propaganda against pre-marital sex." (Stephenie Meyer, the author of Twilight, is a famously abstemious Mormon.) "Males as dangerous, females as victims or prey: what kind of message is that for young women?"

Not long ago, the talk was of Harry Potter and a host of fantasy substrata. One of these, the animal adventure, looks startlingly innocent against the vampires. When Brian Jacques and Dick King-Smith (authors of books such as the Redwall series about mice, otters, squirrels and hares, and the well-loved The Sheep-Pig, respectively) died recently, they left behind legions of fans. But is their pet genre dying with them? There was a 58 per cent reduction in the number of animal stories published for the over-fours between 2000 and 2008. And in spite of commanding a passionate fan base, animal fantasies for older children, such as Robin Jarvis's Deptford Mouse series, my own Tygrine Cat adventures and even the backlist bestseller Watership Down, must creep, pounce and scamper at the edges of a market in which numerous demons jostle for attention.

The decline in animal adventure is part of a wider trend in junior fantasy. While the total number of fiction books for children rose by 26 per cent between 2000 and 2010, this growth is down to the explosion in "young adult" (YA) fiction. The market for pre-teens has contracted, making up only 63 per cent of the total revenues for children's fiction in 2010, as against 85 per cent in 2005. This goes some way to explain the shift from traditional fantasies, featuring worlds inhabited by goblins and elves. Even "soft" fantasy – stories set in our world, but with magical realist elements – have taken a hit, with Rick Riordan's Percy Jackson series among the few to buck the trend.

The winners of the land-grab are undoubtedly subsets of the new horror: vampires, werewolves, angels, faeries and the latest beasties on the block, zombies. Like fantasy, horror is protean – both genres cover a multiplicity of titles, and overlaps exist. In any event, the term "horror" in this context is somewhat misleading: these are books that largely appeal to girls, unlike traditional gore, although the latter has made a resurgence in both comedy and adventure stories aimed at junior-aged boys.

"It is difficult for classic fantasy novels to hold their own in a market increasingly geared towards edgier 'crossover' and YA fiction," explains Claire Wilson, a children's agent at Rogers, Coleridge & White. "The exciting new wave of writing for teenagers inevitably means less room for more traditional genres." Megan Farr from Booktrust agrees that "paranormal romance will still be around for a while", noting another recent trend, the dystopian novel: stories set not in Narnia or Wonderland but in gritty, future worlds, such as Patrick Ness's Chaos Walking trilogy and Suzanne Collins's Hunger Games trilogy.

Booktrust is charged with inspiring literacy and organises the UK's World Book Day festivities, which take place on Thursday. Children across the country are entitled to redeem vouchers against the cost of books at participating stores, or in exchange for a limited number of special £1 titles. One of these titles is a flip-book that combines Philip Reeve's Traction City and Chris Priestley's The Teacher's Tales of Terror.

Despite his acclaim as a horror writer, Priestley would rather chill than revolt. He is critical of the genre's macho tendencies, describing the current appetite for gore as the "literary equivalent of ordering the hottest curry on the menu just for the hell of it".

What does this shift tell us, beyond the observation that an embattled book market is bound to chase trends? The phenomenal success of Harry Potter gave rise to a slew of high-profile fantasy signings, but none rose to its giddy heights, and well-publicised attempts to launch "the next J K Rowling" led to pulped copy and unearned advances.

The worldwide popularity of the Twilight series undoubtedly inspired ghoulish copycats to climb out of their coffins and on to the shelves. But is there more to it than that? If books offer a mirror to our world, what does the current popularity of horror and dystopia tell us?

Hoffman observes: "We are living in a particularly depressing world at present – recession, wars, terrorism, climate change – and teenagers have always been sensitive to the mess the previous generation has made." No doubt there is something particularly appealing to teenagers about dystopia, where common themes of social stratification, brutality and alienation are bound to resonate.

And alienation brings us to the latest trend in teen fiction: science fiction. Ripples are already reaching our shores in the form of I Am Number Four from DreamWorks – out now at a cinema near you. The film is based on a novel and soon-to-be franchise ostensibly penned by a character called Pittacus Lore from the Planet Lorien but actually co-written by James Frey and Jobie Hughes. The story replaces vampire with alien, retains a human girl and is geared towards inspiring similar tremors when these worlds collide.

While we are unlikely to see any goblins for the time being, it is hard to believe that fantasy will retreat for long. Markets are fickle, and the next shock success is bound to spawn imitators, whatever the genre. In the meantime, there is hope for titles with the ingenuity to swim upstream. "Good writing will always come through, regardless of trends," insists Wilson, who like other agents is deluged by bestseller read-alikes but keeps a keen eye out for gems: "The legions of devoted fantasy readers prove the enduring appeal of escaping to another world."

Inbali Iserles is author of the children's fantasy adventures 'The Tygrine Cat', 'The Bloodstone Bird' and 'The Tygrine Cat on the Run' (Walker Books, £5.99 each)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments