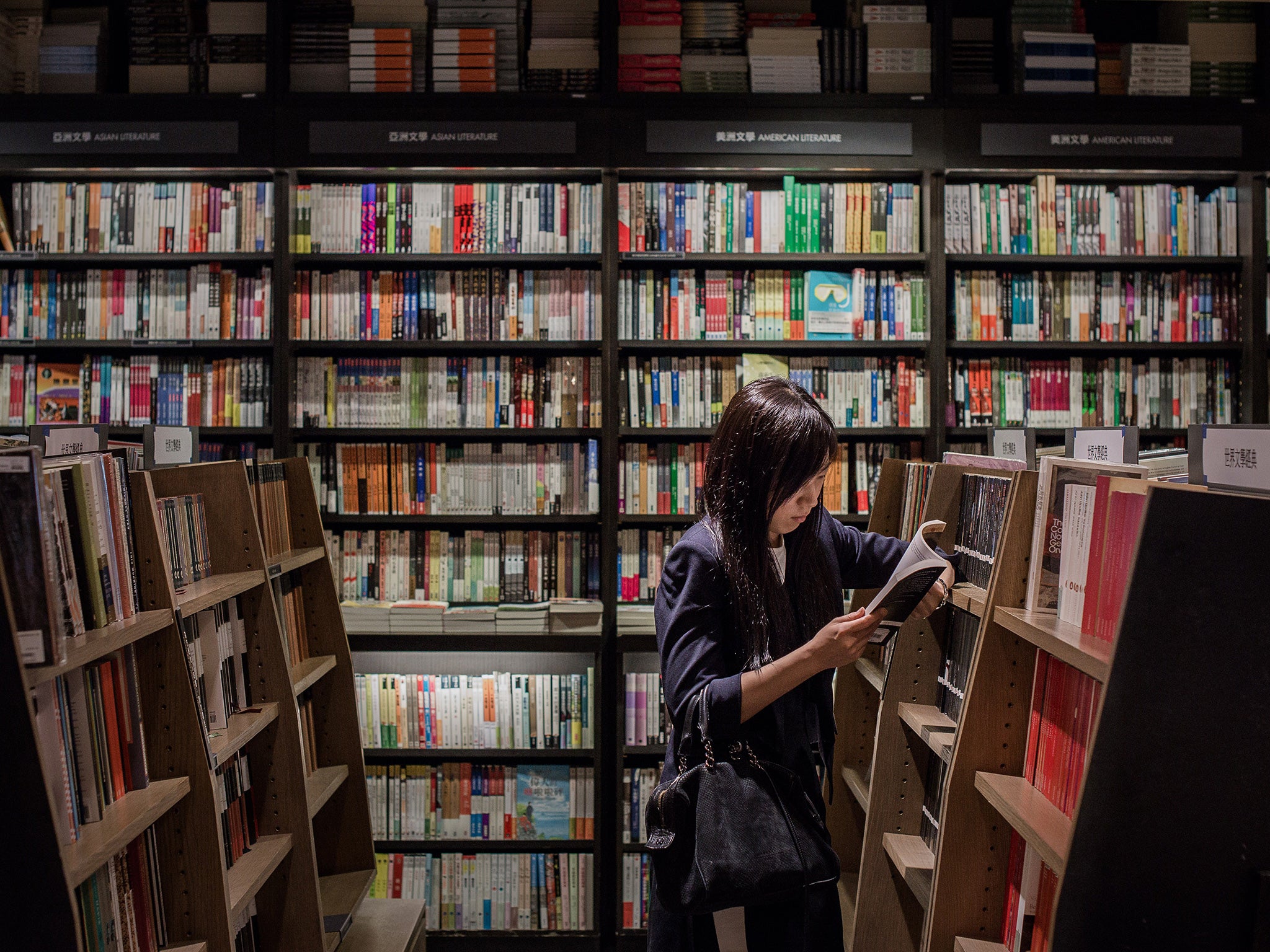

All the world’s a page: One woman's year-long quest to read a book from every country

The response from bibliophiles around the globe was a story in itself

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One drizzly November evening two years ago, I went to Covent Garden to have a beer with a Swiss playwright called Jens Nielsen. We had never met before, but over the two hours we spent together Nielsen shared some of his most personal memories with me. He told me all about his seven-year relationship with the brilliant and troubled writer Aglaja Veteranyi, about finding her body floating in Lake Zurich the day she took her life in 2002, and about how his perspective had changed over the 10 years since her death.

Nielsen felt able to be so frank with me because of one thing: I had read his former lover’s startling first novel, Why the Child is Cooking in the Polenta, and written about it on my blog. Because of that, he was willing to meet and talk.

The conversation with Nielsen is one of a number of powerful, surprising and often humbling encounters that I have had with readers and writers around the planet during and since 2012. That year, realising that pretty much all I ever read were books by British and American authors, I decided to set myself the task of reading a book from every UN-recognised country, plus Taiwan (196 states in all), in 12 months. I quickly figured out that I wouldn’t know where to start when it came to finding or choosing a novel, short-story collection or memoir from most places, so I decided to take my quest online. I set up a blog (ayearofreadingtheworld.com) and asked the world’s bibliophiles to help me.

I knew that I might be on my own with my madcap adventure. By the end of 2011, book blogging was a long-established practice, with giants of the blogosphere like dovegreyreader and readingmatters having banked hundreds of reviews over the preceding five or 10 years. With more than 51 million sites added to the internet in 2012, it was clear that another fledgling blog about books could easily get lost.

Yet, within hours of sharing my plan with friends and colleagues, recommendations were flooding in. Some people went much further than simply offering suggestions. Just four days after my appeal went live, I received a message from a woman called Rafidah in Kuala Lumpur. She offered to go to her local English-language bookshop, choose me a Malaysian book and post it to me. At the time, I was astonished by her generosity to a stranger on the other side of the planet, particularly when the package arrived with not one but two books that she and the bookseller had spent a long time choosing and a card to wish me luck in my quest. But Rafidah’s kindness proved to be the pattern throughout that year. Time and again, people I’d never met went to great lengths to help me, making trips to bookshops and libraries, sending me books and – where there was nothing commercially available – unpublished translations, and helping with my research.

Indeed, in a couple of cases people even produced work for me: the translation I read of the short-story collection O casa do pastor by Olinda Beja was created especially for me by a team of volunteers in Europe and the US after I struggled to find something to read from the tiny island nation of São Tomé and Príncipe off the west coast of Africa. Just by making my reading quest public, I was connecting with people I would never otherwise have come across.

Many of these interactions led to long correspondences and friendships that last to this day. I’m still in touch with Suneetha Balakrishnan, the Indian journalist who helped me to solve the conundrum of what to read from her home country. In fact, our exchanges about the lack of attention paid to Indian literature in translation prompted Suneetha to launch her own Reading Across India project to highlight the wealth of writing in languages other than English in her homeland. And the blogger once called Commonwealthcartographies – aka Jason Cooper – whose chance comment first got me to look at my bookshelves and realise how parochial they were, is a Facebook friend whose film and book recommendations continue to intrigue me.

Although I have never met many of these people face to face, there is a link between us. By reading the same books, we have been visitors to the same imaginary territory. For a short time, at least, we have felt comparable things, our thoughts have travelled along similar tracks, and we have common ground. Because, as the critic, writer and translator Tim Parks puts it, the literary experience depends on “the movement of the mind through a sequence of words”, meaning that reading is nearer than any other art form to “pure mental material, as close as one can get to thought itself”, when you read the same book as someone else, your thoughts are – even if only temporarily and partially – aligned.

The powerful thing about taking this experience online, as growing numbers of people have been doing in recent years – the latest high-profile adopter being Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg, who is inviting followers to spend 2015 reading one book of his choosing every two weeks and to swap views on his A Year of Books page – is that you never know who might stop by and join in. Unlike an offline book club, where the same people, who usually know each other well and often have broadly similar views and tastes, meet regularly to discuss texts, sharing your reactions to a book on an open forum or blog invites anyone who stumbles upon it to get involved.

This can lead to some surprises. I’ve lost count of the number of times a writer has left a comment on a post I’ve written about their book. “Wow! Thank you! I think I’m going to read my novel again,” exclaimed the Barbadian author Glenville Lovell, after I praised his Song of Night. “I enjoyed [this review] and the fact that this project found my book! No greater thing than feedback! Thank you,” chipped in Philo Ikonya after I posted about her novel Kenya, Will You Marry Me?

Similarly, when I published my thoughts on Andorran writer Albert Salvadó’s self-funded translation of his novel The Teacher of Cheops, I was unprepared for the flood of Andorran fans that came pouring onto my blog, full of praise for their hero. If he wrote in English, “he vould be as konwn [sic] as Dan Brown, but such a better writer!!”commented one fan. Suddenly, Salvadó’s stellar sales figures of more than 100,000 copies in his native Catalan and Spanish – particularly impressive when you consider that the entire population of the author’s home country is only around 80,000 – were starting to make sense.

There have been some very touching comments too. It was lovely, for example, to get a message from the tiny Pacific Island nation of Vanuatu assuring me that Sethy John Regenvanu, author of the zestful memoir Laef Blong Mi (about the only published text you’ll find from this country of only 250,000 people), was “still as young as ever”. And I was thrilled when a message popped up to tell me that the person writing had just informed Mr Abdullah Sadiq that I had selected a translation of his version of the classic Dhon Hiyala and Ali Fulhu as my Maldivian choice – and that the author, who writes in the national language Dhivehi, was delighted.

Perhaps the most exciting response, however, came in the shape of a message from a film producer about a year ago. Inspired by my enthusiasm for Tété-Michel Kpomassie’s An African in Greenland, an account of his extraordinary odyssey from Togo to the Arctic to live with the Inuit, she had acquired the film rights to the book and was preparing to meet the author, now in his seventies, in Paris the following week. She wanted to let me know that I would be invited to the premiere when the film hopefully makes it to the big screen in a few years’ time. If I was ever in Paris, I should let her know and the three of us could meet for dinner, she said.

Of course, the fact that anyone can get involved means that there can be challenging comments too. Now and then, I’ll find someone weighing in to criticise the choice for a particular nation. Here and there, a visitor will take issue with my interpretation of a particular text. Sometimes people dispute the categorisation of an author under a particular country – with writers moving around between states and sometimes holding multiple citizenships they can be tricky people to place. And every so often someone will point out an error in the vast list of recommendations on the blog (a collection of all the valid title suggestions I’ve received since the project began).

Indeed, with proposals for intriguing-sounding reads still coming in every day and the curation of the list effectively a part-time job that has to be fitted around my actual working life, it’s inevitable the odd slip creeps in. As the blog’s writer, editor, sub-editor and factchecker all rolled into one, I’m grateful to the throng of more knowledgeable readers and regional experts around the world who sometimes hold me to account and put me straight, usually with enormous grace and good humour.

In a way, this discussion, information-sharing and amendment is a modern-day manifestation of one of the things that that early champion of the idea of Weltliteratur, or world literature, Goethe, envisaged when he argued for greater cultural exchange. Reading more internationally, he claimed, would promote a dialogue conducted “so that we can correct one another”. Nearly 200 hundred years on, I’m certainly seeing the truth of that.

In fact, the ongoing process of correction and re-evaluation that the internet makes possible can fix things much more firmly in your thoughts. With comments popping up on any of the well over 200 book posts now on the site (I add a new one each month), I find that the stories I’ve written about stay in my mind much more vividly than those I’ve read lately but haven’t blogged about. At any moment, someone might engage me in conversation about Galsan Tschinag’s The Blue Sky, Srđan Valjarević’s Lake Como or Andrei Volos’s Hurramabad – books I read well over two years ago, but which remain fresh in my mind because of the initial thought I gave to what I wrote about them and the subsequent discussions they’ve provoked. In the nicest possible way, it’s a bit like living inside a literature seminar – one in which almost any of the 3 billion people currently online might pipe up at any moment.

Of course, no two reading quests are identical, just as no two book-lovers read exactly the same world. I’m sure that, unlike me, Mark Zuckerberg has a team of people to help him vet and respond to comments on his A Year of Books page. He isn’t venturing into the virtual public reading room of the internet alone. Yet with 289,315 netizens liking his project so far, there’s still plenty of scope for varied, joyful and challenging exchanges along the way. Though he is right when he claims that “books allow you to fully explore a topic and immerse yourself in a deeper way than most media today”, he may yet find that some of the most thought-provoking and surprising ideas he encounters in the next 12 months come not directly from the books he chooses, but from the warmth, creativity and generosity of the world’s bibliophiles in response to his quest. If he approaches his public reading odyssey with an open mind, Zuckerberg may embark on a number of meaningful and even life-changing conversations. Who knows? It could alter the story of Facebook itself. In a year’s time, perhaps its founder will be meeting with a virtual acquaintance to discuss the life and loves of one of the authors on his list. Stranger things have happened.

‘Reading the World: Confessions of a Literary Explorer’, by Ann Morgan, is published by Harvill Secker

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments