Alberto Manguel: The spirit of the shelves

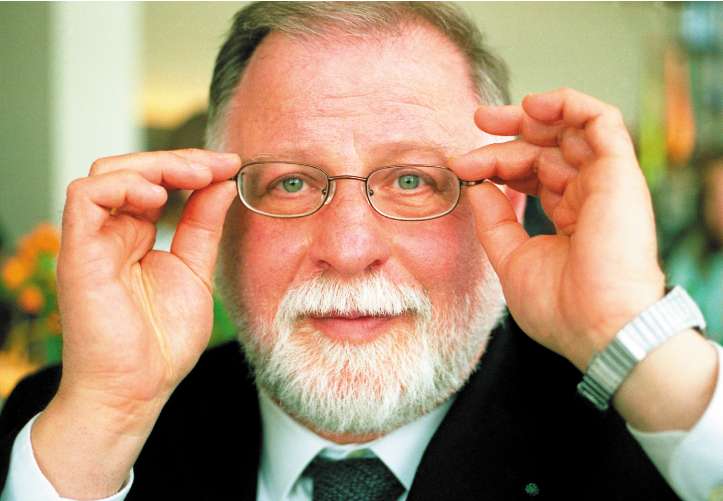

From Argentina to Canada to France, Alberto Manguel crossed a planet of stories, a world champion of books. He tells Boyd Tonkin how he finally found his place

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In a manner of speaking, Alberto Manguel once brought me face to face with Eva Peron. The multi-tasking writer, editor, polymath, linguist, bibliophile – a one-man global campaign for the value of literature and reading in an age that often deems them "a slow pastime that lacks efficiency" – reviewed for this newspaper a novel inspired by the diva turned demagogue: Tomás Eloy Martinez's Santa Evita. To my delight, he delivered not only a review but a precious family photo, of a state banquet in Buenos Aires. There sat his parents (his father served in the Argentinian diplomatic corps) next to the glacially elegant blonde icon.

It was a very Manguel moment. He insists that the arts of narrative construct rather than just reflect our lives, and that "the telling of stories creates the real world". I couldn't gaze at the "real" figure, snapped in her megawatt-charisma prime, without envisaging her ghostly doubles, in image, word and sound, right up to Madonna and those Lloyd Webber wails.

But don't cry for us, Evita. In Manguel's story-shaped universe, the fruits of the imagination nourish our ability to know, to grow and to understand. He commends Richard Dawkins for arguing that imagination is "a way in which the human animal furthers its possibilities of self-consciousness and consciousness of the world, in order to protect that selfish gene. I think he has discovered a very great truth there".

Yes, Manguel is a deeply erudite champion of the book and the reader – as eloquent as any in the world today. We sit in the restaurant of the Royal Festival Hall, where his sculpted answers cut serenely through the din, prior to an event for International PEN's "Free the Word" festival on "the rights of the reader". But the rights of Manguel's reader don't belong in some bookish ghetto. They merge into the rights of the unchained imagination, at liberty to tell and hear the life-giving stories that, according to the lectures published as The City of Words (Continuum, £14.99), "can help the lame to walk and the blind to see". Books pave his road to freedom.

His new work, The Library at Night (Yale University Press, £18.99), is crowded with memorable tales of reading as rescue, as solace, as liberation, in times of want, fear or tyranny. They range from the donkey-back libraries that trek through the mountains of Colombia to the treasured copy of Mann's The Magic Mountain passed around by inmates of the Bergen-Belsen camp. Typically learned, typically charming, Manguel's celebration of libraries of all shapes, sizes and places came about because, at long last, he had one of his own.

After working for a publisher, he left Argentina before the military reign of terror in the 1970s, although its suffering shaped his novel News from a Foreign Country Came. After spells in Europe (he made hippy belts in London) and Tahiti (as a guide-book editor), he moved to Canada in 1982 - at Margaret Atwood's suggestion. Still a proud Canadian, he and his partner relocated to France at the turn of the millennium.

"I could hear the books screaming in their boxes," he reports. "Like everyone else, I had always lived in small places. But now that my children had left home, I thought, maybe I can indulge in having a library." In the southern Loire, he found an old priest's house with a ruined barn attached, in a neighbourhood where "the prices seemed to have frozen before the war... for the Parisians, who set the price of real estate, anything south of the Loire is Africa". A local architect transformed the wrecked barn into a sturdy home – described with envy-inducing relish in The Library at Night – for 30,000-plus books.

So what did it feel like to have them all in place? "I had the sense that something had come, not to an end, but to an age in me. It was as if you have roots for the first time; it's all here. You're somehow complete – coupled with the knowledge that the essence of a library is that it is never complete." Soon after the final tome had reached its designated spot, the barn of books began to overflow. Now they colonise the house, with one bedroom ("we call it the Murder Room") occupied by the detective fiction Manguel writes about so well. The Library at Night wittily shows how every dream of order breaks down, and "the number of books always exceeds the space they are granted". Equally, it argues that the hankering for a flawless system remains a persistent Utopian hope of homo sapiens, the classifying animal.

As a teenage bookworm, Manguel says, "I had a library of maybe 1,000 books in my room in Buenos Aires. I did have the sense that everything there was organised in the right way. You'll probably think I needed serious psychiatric treatment, but there were times when I would not buy a book because I knew it wouldn't fit one of the categories into which I had divided the library." The fledgling bibliophile worked during school holidays in a local bookshop, Pygmalion. Through that job, he became one of the disciples who read aloud to the blind spinner of labyrinthine, enigmatic tales acknowledged not only as Argentina's greatest writer, but as its greatest reader: Jorge-Luis Borges.

It was "an extraordinary privilege to listen to what went on in the mind of one of the great readers". Borges, blind since his early fifties, planned to write fiction again. He "wanted to see how the great masters had put together their work. So he would comment on the mechanics of the story." Yet the young reader would disagree with the sightless sage: "You have to learn to read on your own... This seems presumptuous. But there was in Borges a fascination with the description of violence and a certain prudery regarding erotic stories; he preferred sentimentalism to eroticism."

"For Borges," he recalls, "everything consisted in creating the right structure out of words; we had nothing but the words to go by. Whatever music or meaning the words carried, we had to remember that they were... untrustworthy tools." Borges would criticise the slips of every writer – including that bodger, Shakespeare.

For Manguel himself, a love of books has nothing to do with idolising the fickle business of their making. The City of Words takes aim at the bullying vulgarity of much commercial publishing. Lousy books may always have cluttered the library, but "The bad literature of today, because it exists in an industrial structure that has transferred the methods of the supermarket to the world of art, threatens the existence of the literature that is reality-creating... that sounds very pedantic. Just good literature!" The connoisseur of genre fiction stresses that "In no way am I demeaning writing or any other form of art because it's popular. What I'm saying is that anything fed into the industrial machinery to comply with rules of size and length and shelf-life has a hard time surviving as art."

Ever the heretic, Manguel distrusts the slick, in-house editing that now hammers most books into a conventional shape. "Especially in the English-speaking world, we have come to believe that a work of art is perfectible; that there is something equivalent to a Platonic, archetypal novel... and that there are professionals who will tweak your book to make it correspond to that model. That is a very dangerous concept."

"We seem to live a culture that doesn't want blemishes," he worries. "The vision of most beautiful models... airbrushed in order to be seen as perfect, infects our notion of how literature should be written."

For him, the ghostly flicker of the digital text online may have a similar cosmetic sheen: "a quality of the brief and quick and easy". Conversely, reading in a printed book "entails a certain slowness, a certain depth, even a quality of difficulty... And because we are encouraged to think of difficulty as a negative quality, that becomes a part of the way we look at books."

The Library at Night revels in the physical pleasure of drifting and dipping through the Gutenberg galaxy of ink-on-paper books. Does he ever get rid of them? No, and only one has ever earned the curse of expulsion: "Bret Easton Ellis's American Psycho, because I felt that it was infecting my library". But what if some catastrophe forced Manguel to save a single volume from flame or flood? "I would close my eyes and stretch my hand around, and take whatever book happened to fall into it".

Besides, life without reading might not be real life at all. "I like Cocteau's answer when they asked him, if his house burned down and he had to save either his cat or his Picasso, which would he take with him? And his answer was, 'I'd take the fire'."

Biography

Alberto Manguel

Alberto Manguel was born in Buenos Aires in 1948; his father was the first Argentinian ambassador to Israel. After living in Europe and Tahiti, he moved to Canada in 1982. His books include The Dictionary of Imaginary Places, the novels News from a Foreign Country Came and Stevenson under the Palm Trees; A History of Reading, Reading Pictures and A Reading Diary; his anthologies range from The Gates of Paradise (erotic fiction) to the Oxford Book of Canadian Ghost Stories. Most recently, he has published Homer's The Iliad and the Odyssey (Atlantic), The City of Words (Continuum) andThe Library at Night (Yale). An officer of the French Order of Arts and Letters, he now lives with his partner in central France.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments