A voyage round my father: Kevin Crossley-Holland reveals the 'canker in the rose' of his youth

Authors have a habit of opting for wistful or slightly opaque titles for their memoirs. Kevin Crossley-Holland's choice, The Hidden Roads, seems at first glance to follow this pattern, but, on closer acquaintance, it has a quite literally earthbound significance. For the book recalls how the poet and award-winning children's writer grew up in a cottage below the prehistoric chalk carving at Whiteleaf in the Chiltern Hills, on the Icknield Way, the Neo-lithic track that stretches from Wiltshire, via Oxfordshire, the Chilterns and on through Cambridgeshire. This "hidden road" continues in one of its branches, archaeologists believe, right up to the north Norfolk coast, and it is here, now aged 68, that Crossley-Holland has settled in a converted barn on a chalk ridge a few miles from the sea. "I'm not sure," he admits, "whether it is by chance or by intention, or a mixture of the two."

Puzzling in print how and why such things come about is part of the remit of memoir writing. Sometimes clear answers emerge, but more often it is about making connections, a process Crossley-Holland likens to writing a poem. "What you end up with is not what you set out with, and it would be a bit programmatic if it did. It would suggest something stillborn."

One of the connections in The Hidden Roads is the picture it presents of the writer's musicologist father, Peter, who would recount Celtic fairy tales to his children at bedtime, sometimes accompanying himself on a Welsh harp. Fans of Crossley-Holland's retellings of myth, legend and folklore, notably his bestselling Arthur trilogy for children (translated into 24 languages and with sales of more than one million worldwide) will immediately spot the link between father and son – though in the memoir it is not laboured. "I see the role of the writer," he reflects, "as creating a room with big windows and leaving the reader to imagine. It's a meeting on the page."

The memoir also seems to hint at less obvious ways in which Crossley-Holland's childhood has made him the writer he has become. "I am seriously interested in the psychology of childhood," he concedes. "And I've given a lot of my life to trying to see questions of personal development, as well as the great issues of the day, from a child's point of view. That's certainly true of Arthur. And so much of an author's hoard or quarry is his or her own childhood. I've drawn on it so regularly as a fiction writer and it seemed time to face it rather more full-frontally."

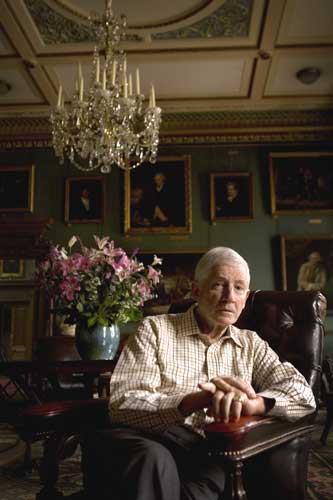

Like many poets, he picks his words with care when he speaks, and often revisits his answers when we've moved on, seeking to give the most honest reply he can. One of the joys of his very joyful book – this is no misery memoir and the twinkly-eyed and agile Crossley-Holland is a glass half-full kind of man – is the evocative recreation of a middle-class childhood of the 1940s and 1950s before televisions and electronic games, when he and his devoted younger sister, Sally, were left free to make their own fun, either in the Chilterns or during holiday visits to their grandparents' home at the salt-marsh harbour of Burnham Overy Staithe, a few miles from where Crossley-Holland now lives.

But part of the full-frontal-ness of the memoir is also its honest acknowledgement that, as well as the idyllic Swallows and Amazons side to his childhood, there was a darker story. There was much unhappiness in his parents' marriage, which endured, in part at least, only for the sake of their children. "What I have tried to do," he explains, "is to imitate a disquiet which now and then surfaced, and is desperately upsetting when you see your mother weeping, as I did. But, as a child, you don't follow through, and ask her a, b, c and d. Rather there is this canker in the rose, this invisible worm and I've tried to reflect that in the way I cast the book, but without banging on about it. Maybe if I ever come to write about my teens and adulthood – and I can't imagine I will – but if I do, then maybe I will want to say a bit more about the ways in which my parents' relationship with one another impacted on me in later years."

As we sit in bright spring sunshine looking out over the lawn that sweeps down into one of the gentle folds of a part of the world that is often mistakenly characterised as flat ("Next year," Crossley-Holland points out, "I am publishing my new and selected poems which I am calling The Mountains of Norfolk"), Crossley-Holland's story-teller's eye falls on the grass. "If we remove this beautiful green skin," he begins, almost immediately hooking me in, "we would begin to find, or not to find, bits of clay pipe, and then, if we are fortunate, bits of green and brown glaze. We need only look at one or two and we would see the shape of the bowl. Then maybe we would find a coin, and the coin was dropped by someone, or hidden, maybe in a little company or nest of coins nearby, and someone would have had to go without lunch or supper because the coin was dropped. Do you see? We are piecing together little bits of evidence to make small fictions which contain truths."

Which, he points out, neatly parallels the process of writing a memoir. But it also reveals the way in which his writerly imagination transcends decades, centuries, even millennia, and brings history energetically alive. As he speaks, I am sufficiently enthused that I would get up there and then and start excavating his back garden if he asked me.

That willingness, when I admit to it, takes Crossley-Holland back again to his father. "He was a seeker, a quester. I learnt far more from him that I am grateful for than things that I still resist or try to put right. I learnt from him this love of the layers of time, this wonderful sense of the lores, the language, the coins in our pocket, the truths in the lie of the land, all being a continuum."

That paternal influence lives on in him, he concedes, when he goes into schools to work with children. "There is a way in which I try to look at objects and ask questions. So with the children, I will show them a medieval key, show them that the teeth of the key appear to have the characters 'c' and 'f', and then build the story out of that."

And what of his mother? What of her is to be found in his life and in his writing? "My mother was the doer," he says affectionately. "From her I get the sense that I must be a perfectionist about everything I do, whether it be writing or whatever. And she was also a very good businesswoman. [After her divorce, she founded and ran a gallery in Oxford.] I have inherited something of that from her. It made my first job after university in publishing almost the perfect one for me because it was where aesthetics and economics met."

That career choice came only after Crossley-Holland had abandoned plans to seek ordination – influenced by his father, who challenged him to find out more about other faith traditions than Christianity. His life subsequently has followed – to take his own Hidden Road metaphor – many twists and turns as a publisher, poet, translator from Anglo-Saxon, librettist and academic in the United States where he met his wife, Linda. He has four grown-up children from previous marriages. "Sometimes people ask me what I really do," he jokes, "but I try to see the different parts as spokes to and from the hub where the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. They all depend on each other."

Crossley-Holland's name has been mentioned repeatedly in recent months in the context of one particular spoke of his many-faceted career – the forthcoming vacancy for a new Children's Laureate. It is hard to imagine a better stage for using the talents learnt way back down the hidden roads in his own childhood.

The extract

The Hidden Roads: A Memoir of Childhood, By Kevin Crossley-Holland (Quercus £16.99)

"...Once, when we were standing on top of Whiteleaf Hill looking west over the Vale of Aylesbury, I asked him how far we could see... After a while, he said, 'Well, as far as Oxford... the Cotswolds. As far as Wales, do you think?' Immense as the view is, this was... impossible. 'Well,' said my father gently, eyes closed, 'if you close your eyes and open your eyes, you may be able to. On a clear day.'"

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies