Fifty years after the madness sparked by Mao’s Cultural Revolution, a book uncovers horror of mass murder spree

In 1967, a two-month orgy of violence and hysteria swept a rural province in China and an astonishing 4,000 people were brutally slaughtered. Without the bravery of Tan Hecheng, the story of what happened to these ‘black elements’ would never have been told. David Barnett on the journalist who uncovered the Killing Wind

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When he was a high school student in Changsha, the capital of the Hunan province in south central China, Tan Hecheng accompanied an older cousin to meet some of his friends in the Dao County area, a long bus ride away. While his cousin caught up with his friends over stewed fish and rice wine, Hecheng went for a walk around the town of Daojiang, the first distant town in the open countryside of China he had ever been to. This was late in 1967, a year after the start of Chairman Mao’s Cultural Revolution which would last a decade and which would attempt to impose a pure Communist ideology across China, wiping out anything deemed capitalist, traditionalist, or bourgeois.

Hecheng was 20 at this point, and a student, and knew full well the impact the Cultural Revolution was beginning to have. But some aspects of it, especially here where he found himself in the more rural corners of the provinces, still had the capacity to surprise. Walking across a pontoon bridge and examining a city wall archway, Hecheng found a handwritten notice pasted to the granite wall, claiming to be news of an official investigation into several named “reactionary landlords” who were guilty of “heinous crimes including persistent reactionary standpoints, score settling and resistance to remoulding and a poor work effort”. The notice, signed by the Head Judge of the Supreme People’s Court of the Poor and Lower-Middle Peasants, was dated some months before and concluded chillingly: “Public wrath demands their execution… they are sentenced to death, effective immediately.”

Hecheng says the prospect hit him hard: “My heart began thundering in spite of myself, my scrotum shrivelling into a tight little ball as my scalp tingled.” He ran back to find his cousin and his friends, thinking, “Although I’d long become inured to the many fantastical oddities emerging from the Cultural Revolution, this notice and this ‘court’ took me completely by surprise.”

In the early days of the Cultural Revolution, not everything that went on in the battle to cleanse China of capitalist influences was widely known about. Property was seized, torture carried out, people imprisoned on the flimsiest of pretexts. Young people, like Hecheng’s cousin and his friends, had been sent what became known as “down to the country”, transplanted from their urban homes to rural areas for “re-education” and to instil a strong work ethic. These were the “fantastical oddities” of the Cultural Revolution.

However, when Hecheng got to his companions, they were nonplussed at his reaction. His cousin shrugged and told him: “Lots worse things went on.” But nobody could satisfactorily give Hecheng any explanation for the deaths; the young people like his cousin who had been sent to the countryside for re-education had gone back to the cities to continue the “revolution” by the time the worst of what would become known as the Daoxian massacre took place. And it would take Hecheng another two decades to properly get to the truth of the matter.

But that day in Daojiang he had stumbled on another facet of the Cultural Revolution that could not in any sense be dismissed as an oddity… it was the systematic murder, over 66 days in 1967, of an astonishing 4,000 people, a kind of insanity that spread out to the surrounding districts and eventually resulted in the deaths of 9,000 men, women and children, who were considered enemies of the Maoist government. And it might have all been suppressed or forgotten, had Hecheng not become a journalist and taken an assignment in 1986, which gave him access to a large quantity of classified documents relating to the Daoxian massacre and which prodded the memories of the feelings of horror he had felt on that innocuous day trip 20 years earlier.

Hecheng had stumbled across journalistic dynamite. But even though the Cultural Revolution had come and gone, and ostensible reform had taken its place, China was still mired in bureaucracy and close scrutiny was given to anything that might be deemed damaging to the government. It was journalistic dynamite, that, were he not extremely careful, could quite easily blow up in his face.

Chinese journalist Yang Jisheng, who wrote an extensive investigation into the 1959-1961 Great Famine, called Tombstone, says: “I know very well what it is to undertake this kind of journalistic inquiry in mainland China and the risk and political pressure it entails. In compiling these records, Tan took a heavy cross upon himself, and his life entered a new trajectory. Most of the information currently circulating in China and abroad regarding this massacre is the result of Tan’s reporting and is only the tip of the iceberg.”

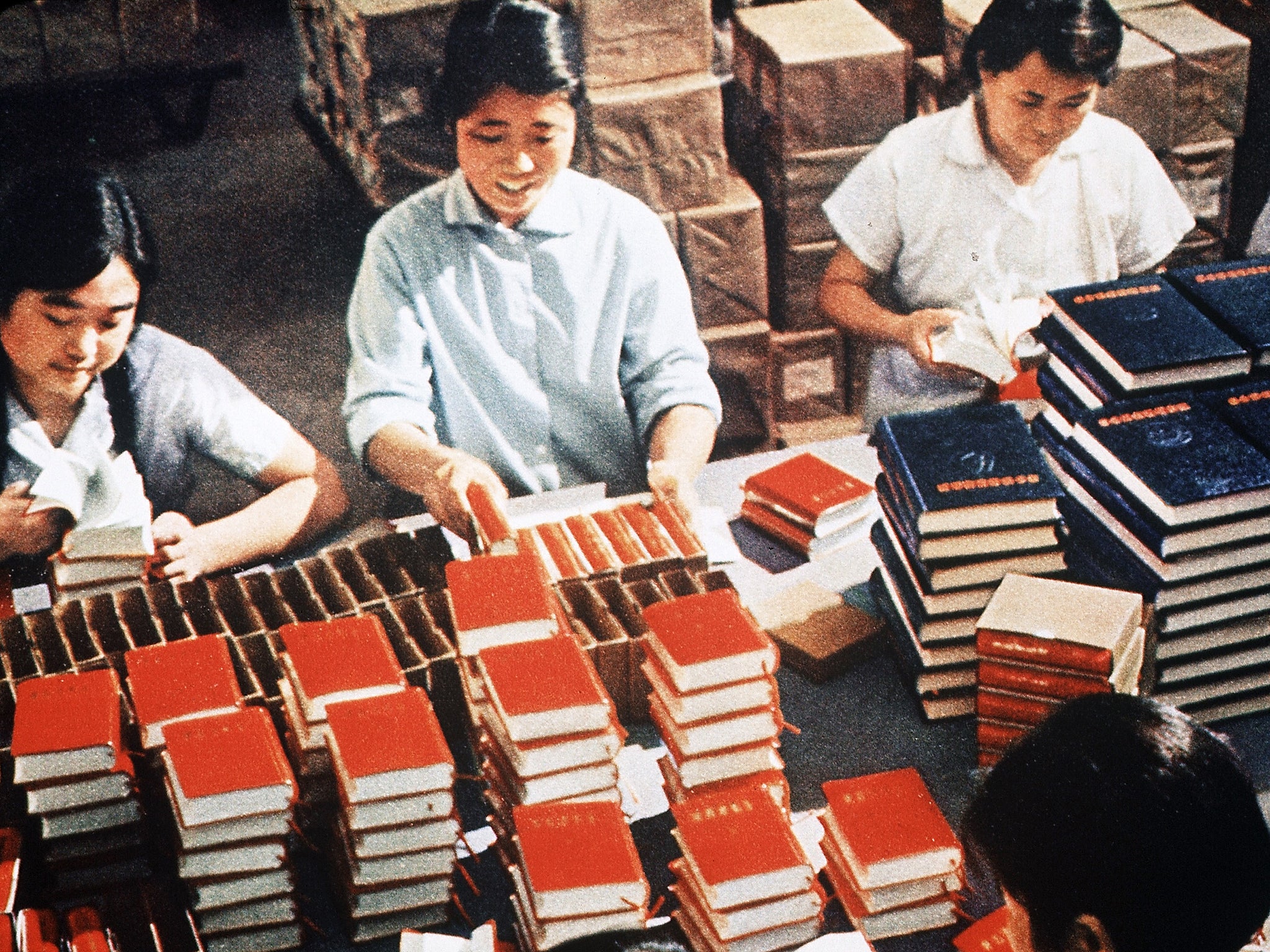

Naturally, Hecheng was banned from publishing the results of his investigations into the classified documents, and his subsequent visits to the Daoxian region to find out precisely what had happened. But in 2010 he published, in Hong Kong, no longer under mainland control, a Chinese language edition of his findings, which was titled after the name rural peasants in Dao County gave to the period between 13 August and 17 October 1967, when the massacre took place: The Killing Wind.

But, aside from the rather abstract information that 4,000 people died in 66 days, what exactly was the Daoxian Massacre, the Killing Wind, and why did it happen?

Perhaps the most startling image from Hecheng’s book, now translated into English for a brand new edition on the 50th anniversary of the massacre, is the description of the Xiao river bloated with dead bodies; children dance on the banks of the vast river, counting the corpses which flow past a hundred an hour, until they become tangled and bottlenecked at the Shuangpai dam. It takes six months to clear the hydropower generators of bodies; it is two years before local people will eat fish from the cadaver-stuffed river again.

The propaganda was taken on board by rural people in Dao County with a passion bordering on frenzy. There were black elements everywhere… your neighbour could be one. You could have them in your own family

The bodies that had been cast into the Xiao had been murdered with farming tools, spades, hoes, sticks. Others had been thrown into limestone pits… sometimes without even being killed, suffocating in a rapidly filling mass grave. And when their killers were feeling particularly creative and had time on their hands, they would practise “the Celestial Maiden Scattering Flowers”… several people would be tied together and blown up with dynamite, flesh, bone and body parts scattering the surrounding area. Those killed were described by Maoist propaganda as “black elements” – capitalist, bourgeois, traditional.

They were said to be landlords — a heinous crime, profiting from the land others had to live on — or capitalists… even a simple shopkeeper could be classed as a capitalist. Anyone who had voiced seditious sentiments a decade or more before the Cultural Revolution would be fingered as a black element, anyone who had a job that was part of the previous infrastructure. Homosexuals, of course, were black elements. The propaganda was taken on board by rural people in Dao County with a passion bordering on frenzy. There were black elements everywhere… your neighbour could be one. You could have them in your own family.

Over August 1967, the fear of black elements within the province began to reach fever pitch. The atrocities of the Cultural Revolution are well-known. But most focus on what went on in the cities, with the Red Guard carrying out Mao’s orders against suspected insurrectionists. What happened in Daoxian was another level… Chinese against Chinese, villager against villager, farmer against farmer, with enmities and suspicions breeding and spilling over into a two-month orgy of madness and murder.

Yang Jisheng says: “Under this totalitarian system, a portion of the people, perhaps five per cent or more of China’s population, were labelled as a political underclass. Year in and year out, day after day, the media tools of the state apparatus demonised this particular underclass until they were considered worthy of death.”

Song Yongyi is a librarian and professor at the John F Kennedy Memorial Library of California State University. He was jailed twice during the Cultural Revolution for belonging to a “counter-revolutionary clique”. He says: “Tan Hecheng’s investigation shows us that ‘black elements’ and their off-spring were an underclass suffering horrendous and social bias who had become so disempowered under the long-term dictatorship of the proletariat that even as they faced their deaths, the didn’t dare ask the simple question, ‘Why do you want to kill me?’ There is no justification in international law, in China’s own laws, or even in the superficial policies of the Chinese Communist Party for the killing of unarmed and peaceful citizens, not to mention women, the elderly and children.”

Whether the Killing Wind was an infected madness that swept across Dao County, or the opportunity for old scores and enmities to be settled or acted upon, it resulted in a horrendous death toll… with victims ranging, says Song Yongyi, from 78 years old to, heartbreakingly, just 10 days old. And without the bravery of Tan Hecheng, 30 years ago, acting to bring the facts he uncovered to world attention against the wishes of the Chinese censors, the Daoxian massacre might, like the thousands of innocent victims slaughtered and left in mass graves, have remained buried forever.

The Killing Wind by Tan Hecheng is published by the Oxford University Press

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments