How the great writers published themselves

What worked for Sterne, Proust and others is now being done on the internet by a host of aspiring authors, says Christina Patterson

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Proust did it. Sterne did it. Luther, Whitman, and Pound did it. Dickinson, Hawthorne and Austen did it. So did Walcott and Woolf. And what Marcel Proust, and Laurence Sterne, and Martin Luther, and Walt Whitman, and Ezra Pound, and Emily Dickinson, and Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Jane Austen, and Derek Walcott, and Virginia Woolf all did, at least according to an exhibition newly opened in York, was publish, or pay to publish, their own work.

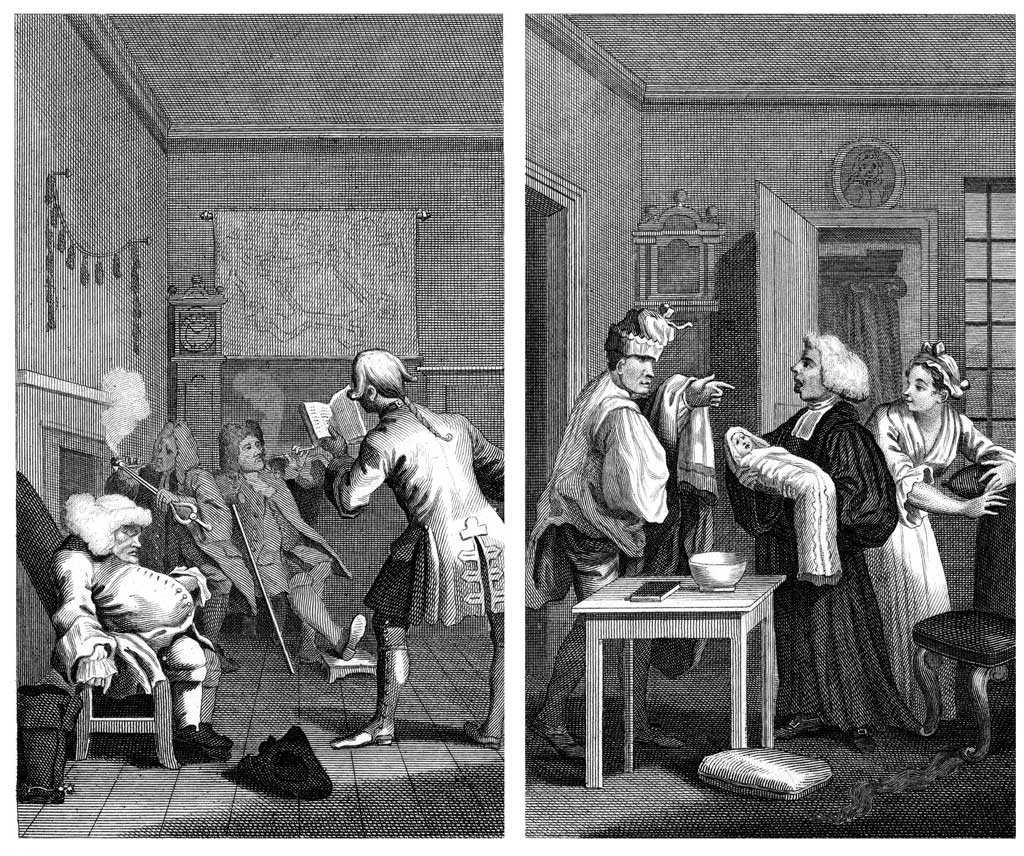

The exhibition, which first appeared at the Whitechapel Gallery in London, is called DO or DIY. At the Whitechapel, the pages of a "polemical essay" that mentions all these writers, and that was meant to be "an introduction to the concealed history of do-it-yourself publishing", were displayed on the walls. In glass cases, you could see original editions of some of the writers' self-published works. You could, for example, see Pound's A Lume Spento, which he sold at 6 pence each, Woolf's Between the Acts, published by her Hogarth Press, and a poetry book by the 11-year-old John Ruskin, published by his doting dad. In this new exhibition, at Shandy Hall, in Yorkshire, where Sterne wrote Tristram Shandy, the pages of the essay are scattered through the garden, and blown up on boards.

"Sterne couldn't get his book published," explains Patrick Wildgust, who lives at Shandy Hall and runs it as much more than a museum. "So he had it printed himself. He had to borrow the money, and marketed it in his own eccentric, peculiar way. So it seemed appropriate," he says, "to have that argument here." And you can see why he'd think it would. Tristram Shandy is one of the funniest novels in the English language. It's also one of the first great experimental literary works. Sterne was "the progenitor of experimental literature", according to Simon Morris, from the writer collective, called information as material, which has put this exhibition on. He wanted, he says, to see "what language can do".

And so, it turns out, does Morris, who describes his collective as the largest publisher of "uncreative literature" in the world. "Uncreative literature", for those of us who haven't heard of it, seems to involve a lot of copying of other texts. The American writer Kenneth Goldsmith, for example, who was invited to the White House in May, copied out a whole issue of The New York Times and published it in a book he called Day. Morris himself has copied out the whole of Kerouac's On the Road. "I copied a page of his text a day for a year," he tells me, "and uploaded it into a blog. Because of the nature of blogs, the last part is the first part. My book goes from east to west". He has published 12 books himself, and "not a word of them" is his own. "I've had offers from publishers," he says, "but I prefer to stand behind my work".

In this, he is hardly alone. "Non-traditional publishing", which is one way of describing the mass of digital options now available to would-be writers, went up by 169 per cent last year. Readers are now buying more e-books than printed books, according to Amazon, and many writers aren't bothering with publishers, or books. "Writing in a digital age," said the novelist Hari Kunzru at a conference a few weeks ago, "doesn't just mean changes in distribution, but in the way literature is produced".

The conference, which was called Writing in a Digital Age, was put on by The Literary Consultancy, a professional advice and manuscript-assessment service set up to help writers get published. When it started, in 1996, the main emphasis was on how to get your work good enough to get an agent. Since then, everything has changed. "The digital age does ask us questions about authorship, and originality," said Kunzru. "It's interesting to ask why the literary world is so attached to an idea of creativity that seems to come from an earlier time."

Well, yes. And no. It is interesting to "ask questions" about authorship, as Simon Morris and his collective seem keen to do. If you're using other people's work, in what Morris calls "conceptual writing", and in what Kunzru calls "bricolage", it does, as visual artists love to say, "raise questions" about who produced the finished product. And if you're inviting readers to take part in an "interactive" storytelling experience, or make contributions to something you started, you couldn't really say that whatever you end up with is just yours.

But let's be honest. This kind of experimental, interactive stuff isn't what most people read, or want. It isn't even what most writers want. It isn't even what Hari Kunzru wants. "I write novels," he said, "that get published in the traditional way. I do other things," he added, "but mostly not for money".

Ah yes. Money. That, after all, is what most writers want. Nicola Morgan, who has written 90 (yes, 90!) books about writing and publishing, and some that came out of a blog, told the conference that writing "in a digital age" had brought her a bigger profile, and readership, but that she had paid a "heavy price". By filling her life with "interactive chatter", she had, she said, lost "space to think" and part of her soul. Kerry Wilkinson, who wrote and published his first novel, Locked In, on a netbook that cost £160, with no professional support, said he had "wanted something to do". His first three self-published e-books sold more than 250,000 copies in six months. But in February he signed a six-book deal with Pan Macmillan. Having an editor was, he said, "cool".

Robert Kroese, author of Self-Publish Your Novel: Lessons from an Indie Publishing Success Story, decided to publish his own work because he thought traditional publishing was "like trying to get into an exclusive club". You're not, he said, "even sure what's in the club, and there are some people who are coming out of it and saying 'well, that wasn't worth it'." His first novel, Mercury Falls, sold about 5,000 copies, in print and e-book, in six months. Then it caught the attention of the publishing arm of Amazon, who re-released it, and it sold 50,000 more.

"There was a moment," he said, "when I was almost an overnight success." But Kroese was, and knows he was, lucky. "Unless they already know you," he said, "very few people are going to spend money on your book". He's also the kind of man who builds his own house. A plumber who visited the site pointed at a correctly connected pipe and told him it was the only thing he'd got right. "If you're the kind of person who looks at a project like that," said Kroese, "and thinks 'I can do that', then self-publishing might be a good thing for you."

The trouble is, most of us aren't. Most of us are good at some things – for example, writing – but not always at the marketing, publicity, and relentless self-promotion you seem to need to make a book sell. We might be good at writing little pieces, and not at structuring something over several hundred pages. We might find that something that sounds easy isn't.

Some of us might think Tristram Shandy is one of the best novels ever written, and that some of the work it inspired is also quite interesting, and that experimental, interactive work can be, too. But we might also think that a little experimental work goes quite a long way. We might think that the sometimes-too-brave new cyber-world that has replaced the traditional literary landscape has a lot of interesting things to offer, some nicely written things, and some really good things, but that it also has an awful lot of dross. We might feel that when time is short, and life is short, we don't want to wade through dross.

We might also feel that we've been very, very lucky to be alive at the time of the greatest invention since the printing press. We might see that this gives us possibilities to read, and write, and publish, that no generation has had before. And we might feel grateful for the Prousts, Sternes, and Woolfs, who took a risk to publish work the world took up. But we might also remember that most writers, and certainly most writers who publish their own work, don't write like Proust. We might remember, as Robert Kroese says, that "the average return of the self-published book is £500". And that the odds of being successful on either side of the publishing divide are, as he also says, "very poor".

DO or DIY, Shandy Hall, Coxwold, Yorkshire (www.laurencesternetrust.org.uk) to 31 August

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments