Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power, Tate Modern, London, review: fascinating and necessary

A wide-ranging show of work between 1963 and 1983 explores art’s role in the struggle to create a black identity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This huge show is both a visual presentation and a densely worked, heavily documented argument. It is the story of the emergence of black art in America during the fraught, politically contested era of 1963 and on. It takes in movements, key historical moments across the nation – the death of Martin Luther King (his soaring voice greets us as we walk into the first room), the Watts riots in Los Angeles, the emergence of the Black Panthers – and it shows us the art which emerged as a direct consequence of the struggle to create a black voice, a black identity.

What was this art to be? Could there, should there, be a distinctly black art at all? How much of it would come to depend for its effectiveness upon collective endeavour? There are so many questions here sniffing around for answers.

All very fascinating. All very necessary. All very informative. All very worthwhile. Seldom will you have read so many detailed wall texts, and scrutinised so many newspaper cuttings with a sense of slight unease that you had barely remembered so much of this, and then, redoubling your efforts to engage with it all over again. You remind yourself, with a renewed passion borne of a degree of shame, of what went on in Chicago, Philadelphia, Washington, Harlem, and why it mattered so much to so many of the disempowered.

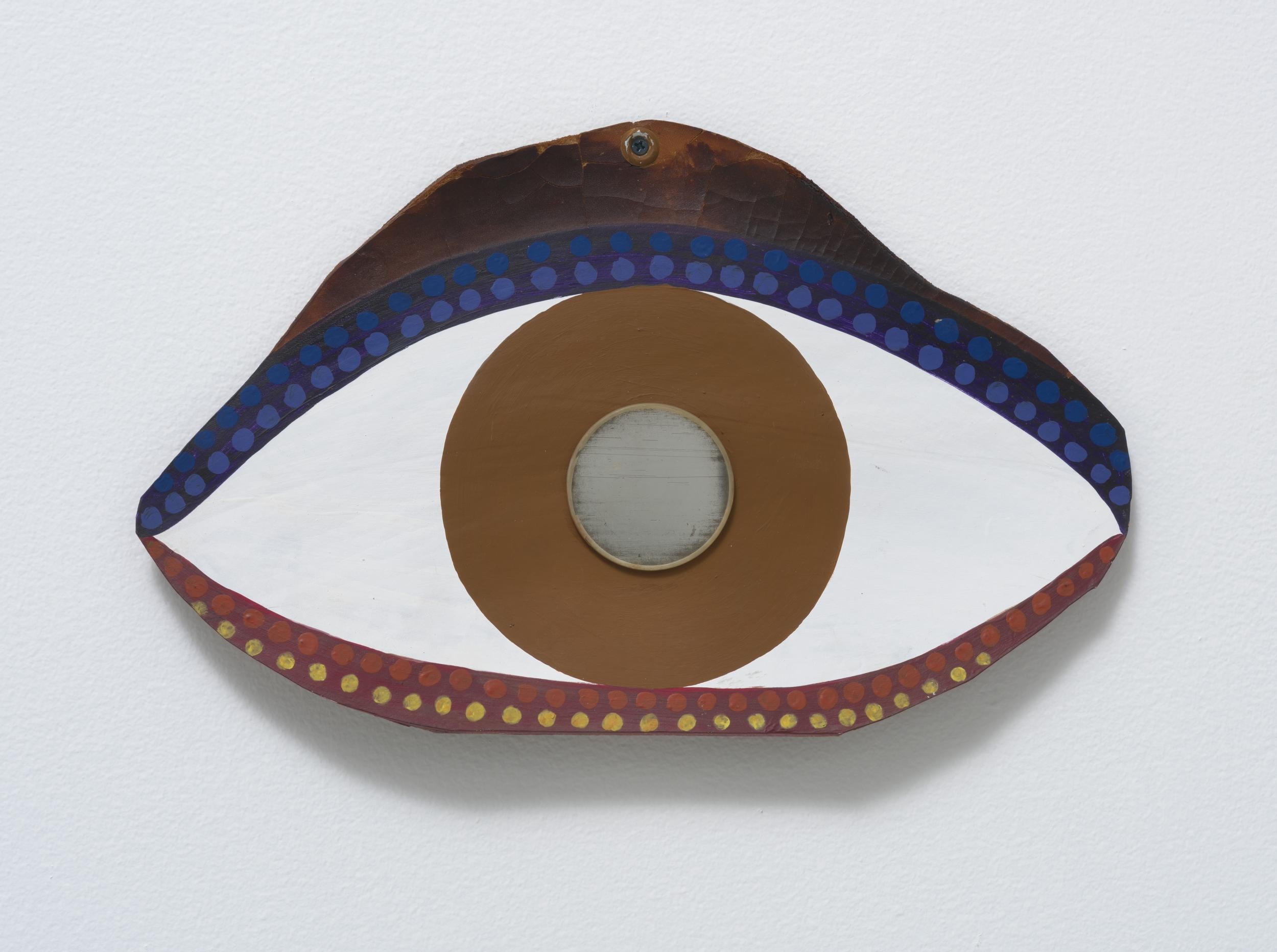

Much of the art is an immediate, visual channelling of fist-shaking rage, a call to arms: art for the walls of the South Side of Chicago, art for the newspaper. Some of the best of it, from first to last, comes in the form of collage – look at the wonderful examples by Romare Bearden in the first room, for example – and this is perfectly understandable because collage is all about the scavenging of bits and pieces, from here and there, and then transforming these fragments into new wholes. Nothing settled. Nothing precious. Nothing sanctified by long tradition.

The best rooms are the early ones. They are also the ones densest with fact and documentation, with the fever of beginnings, the defining of territory. A bit later on, things begin to slacken off, in quality and focus. The room devoted to Africobra art feels lightweight, too much about surface sheen and glitziness. A room about black heroes feels a bit makeweight too – as does its theme, as if the show had decided to relax into a degree of self-preening. There are some damp squibs. Here is a portrait by Beauford Delaney – of a very indifferent quality, it has to be said – which may or may not be a likeness of James Baldwin. It was certainly owned by him, but it doesn’t look like him. Why include it then when it’s not even worth showing? One or two silly things are said about black artists and abstraction.

There are remarkable moments too though: Sambo’s Banjo, for example, by Betye Saar, in which the banjo case opens to reveal a hanged corpse beside a hanged skeleton, or the rich, tonally dark photographs of Roy DeCarava, or the forceful simplicity of Faith Ringgold’s posters.

All told, it was a tumult of awakenings.

Soul of a Nation: Art in the Age of Black Power is at Tate Modern in London till 22 October, tate.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments