Signs of a Struggle, V&A, London

Subversion and subterfuge are at the heart of this trawl through 40 years of Postmodern photography

It sounds suitably postmodern to put on a display accompanying an exhibition that's not even on yet, but Signs of a Struggle: Photography in the Wake of Postmodernism is only a taster of what's to come next month in the V&A's blockbuster: Postmodernism: Style and Subversion 1970-1990.

While that survey will kick around architecture, art, film and fashion in an attempt to chart an unchartable style, this focus on Postmodernist photography of the past 40 years is perhaps better described as a soupçon of that bigger show, that word deriving from the French for suspicion.

Nothing here can be trusted: not the dreamy waterfall in the Lake District by John Pfahl – actually a heavily doctored image beautified by hitting the watercolour effects palette in Photoshop – and certainly not the vintage-looking print of a stone-sculpted Egyptian princess, in fact a recent photo by artist Sarah Pickering of a modern fake, which itself once fooled a museum enough to buy the forged artefact.

There are lots of "ofs" in Postmodernism. So we have a photo of a photo of an advertisement by Richard Prince, a photo of a model of an apple by James Casebere and a photo of a mock staging of the aftermath of a party by Anne Hardy. Of course, Prince's heroic Marlboro men, without the telltale logo to turn the tobacconist's horsebound cowboys into a dusty, hazy mirage of the American dream, are now considered the height of Postmodernist parody, appropriation and artifice, exemplifying that sense of everything being at more than one remove from its subject matter.

But we Brits have also turned our hand to subverting and subterfuge, as in John Kippin's Nostalgia for the Future, where the rusty ship of progress is run aground on a typically English beach, with a mournful caravan and the title's text interrupting the foreground. Another very British rupture is Peter Kennard's Haywain with Cruise Missiles in which Constable's Suffolk idyll is disturbed by a missile launcher atop the old horse-drawn cart, although such Bansky-level blatancy marks Kennard out more as agit-propper than Postmodernist. David Shrigley's trompe l'oeil packet of carrot seeds replacing a plant in a flowerbed is too slight by half and ridiculed by the nearby collection of carrots, lettuce, tomatoes and spring onions by the Belgian joker Marcel Broodthaers. His odd recipe neatly represents the crisis of selection and representation from which the artist somehow still has to fashion his own visual stew.

The best single work, David Hockney's Photography Is Dead, Long Live Painting shows two vases of sunflowers, one real, the other painted in anamorphic perspective over two pieces of paper. The two versions compete for our affections and question whether a painting of an object could ever compete with a photograph of the same thing. Hockney proves that painting can better mere lifelikeness, by adding flashes of yellow shooting off the painted sunflower petals.

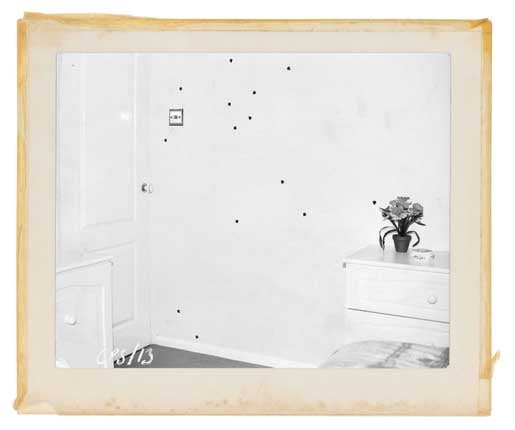

Clare Strand's series of crime re-enactment scenes that lends this show its name, Signs of a Struggle, rightly gets its own evidence room. Numbers, letter, crosses and arrows mark the spot of unexplained misdeeds, perhaps pointing out fingerprints, blood trails or worse. Are Strand's pictures actual archive shots or just carefully posed deadpan versions of a peculiar case of photography up to no good?

More nagging than the "ofs" are the "what ifs". What if they hadn't included the solitary Cindy Sherman or Jeff Wall? What if they'd shown a work of reportage by Martin Parr? Now that Postmodernism has become a dustbin into which historians of recent art can drop difficult artists, anyone in the image business could be found guilty. This uncertainty will surely tinge the V&A's main event too, because even after you've ticked off all the bright Po-mo colours and Rubik's Cube graphics, what couldn't you throw into to this almighty bouillabaisse of a style?

Ossian Ward is visual arts editor of 'Time Out London'.

Next Week:

Marcus Field surveys Mat Collishaw's Sordid Earth at the Roundhouse

Visual Choice

Tony Cragg's monumental and meaningful sculpture is a highlight of a packed programme of art at the Edinburgh International Festival. Colossal, fluid pieces (above) occupy the whole ground floor of the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art (0131 624 6200) – and stay there long after the festival frenzy has died down (to 5 Nov).

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies