Monochrome: Painting in Black and White, National Gallery, London, review: I was not bowled over by it

It explores the tradition of painting in black and white by old masters such as Van Eyck, Dürer, Rembrandt, and Ingres alongside works by contemporary artists working today, including Bridget Riley

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

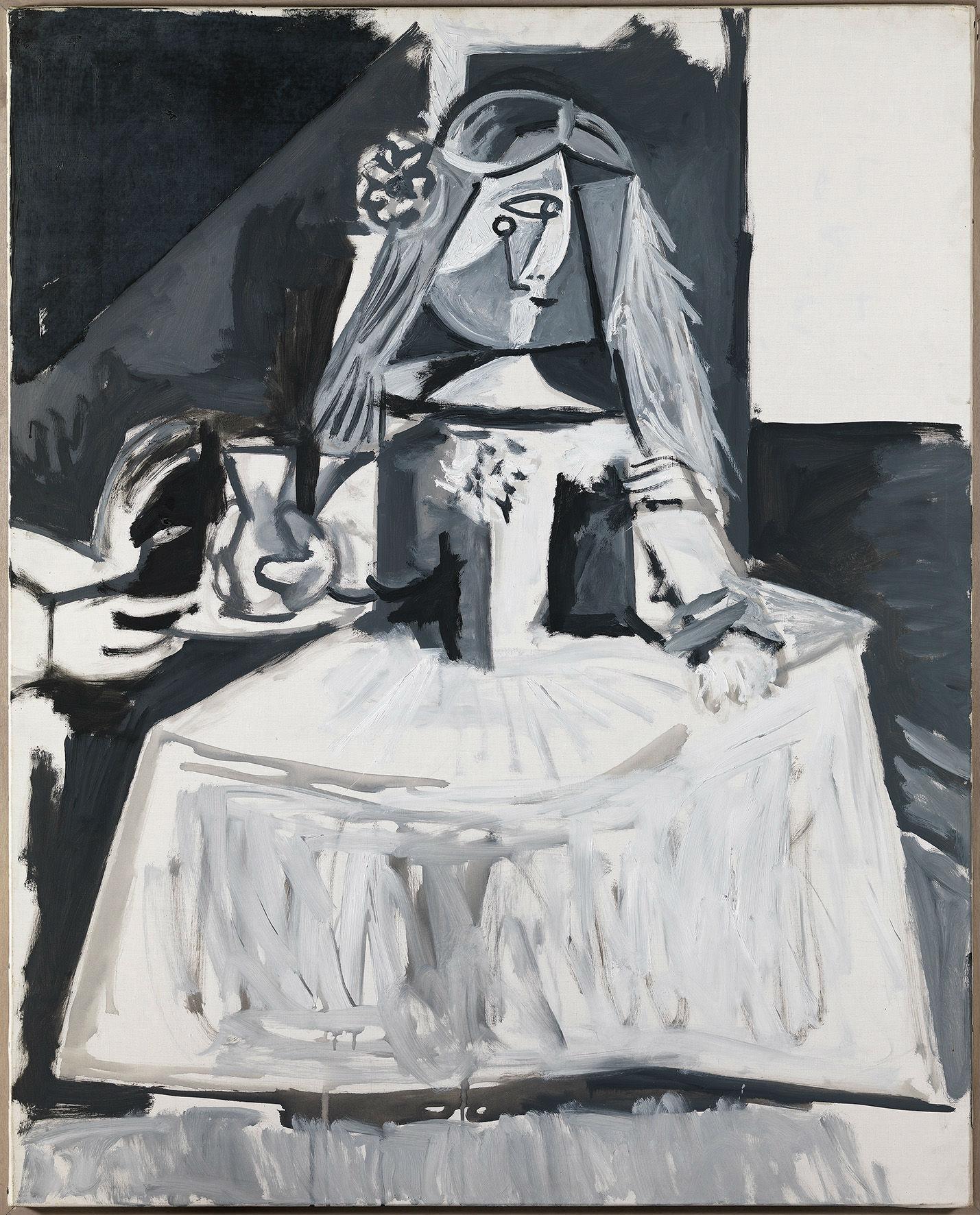

Your support makes all the difference.This is a perplexing show, taking us on a journey through seven centuries of art in monochrome. Some of its ideas don’t stand up to too much scrutiny, and the curatorial arguments are not always best served by the choice of National Gallery images and loans. I was not bowled over by the show but there are many intriguing works to enjoy along the route. The elephant in the room – or not in the room, in this case – is the greatest monochrome picture of them all, Picasso’s Guernica. Also missing are the Spanish artists who served as Picasso’s great sources of inspiration, notably Velazquez – that absolute master of black and white – and Goya, in whose hands a restricted palette of “black”, “black and white” or “earth” becomes the very stuff of nightmares. Instead, we are treated to a strange whistle-stop tour that takes us from 14th-century stained glass to Olafur Eliasson’s 1997 installation Room for One Colour.

In the first part of the exhibition we learn that the use of black and white in devotional images was often associated with religious asceticism; for some religious orders, colour was considered superfluous and distracting to the senses. A piece of medieval glass with black and yellow images provides perhaps not the most potent of illustrations. A Memling altarpiece of the Virgin and Child with Saints and Donors in the same room, seduces us with its brilliantly coloured interior painted in oils, glimpsed through partially closed shutters that are painted with grisaille (grey scale) figures. These monochrome figures of saints are intended to imitate and blend in with the sculpture and architecture of their surroundings, to give a masterly allusion of stone and three dimensionality. They are no more or less profound than the richly coloured holy figures that provide a moving counterpoint.

The relationship between preparatory sketches and finished works in colour is also explored, to show that artists “think without colour first”, making their closest observations in light and shade. Independent paintings in grisaille are presented as a radical break with tradition, ushering in a 16th-century aesthetic for finished works in black and white, which occupy a place somewhere between painting and drawing. A surprising omission in this context is the role played by Leonardo and Michelangelo’s large-scale preparatory drawings – known as Cartoons – that came to be celebrated and collected as stand-alone masterpieces.

This scenario takes us to the world of sculpture versus painting, to Classicism versus Romanticism. The marvellous Ingres’s Odalisque in Grisaille – the poster-girl for the exhibition – is a reduced monochrome repetition of Ingres’ 1814 masterpiece (painted with the aid of his workshop). It is both a grand nude in the neo-classical style, but also a young woman, deceptively real even when drained of the colour that proves she’s flesh and blood. This picture would not have looked out of place in a later room of paintings inspired by the repetitious, immediate, and super-real art of film and photography (featuring the likes of Gerhard Richter and Chuck Close).

A penultimate room deals with abstraction, with Malevich’s revolutionary black square floating on white as its central focus. Works around it range from Elsworth Kelly’s Black and White Bar 1 to Bridget Riley’s op art black and white dazzler. The exhibition ends with a grand flourish: Olafur Eliasson’s Room for One Colour, in which sodium yellow lamps suppress all other light frequencies, reducing everything in the room – notably all of us – to black and white. The artist encourages us to take photographs; this is, of course, the obligatory Instagram moment. We can capture each other in glorious monochrome, and notice how every granular detail – every blackhead – is exposed!

‘Monochrome: Painting in Black and White’, National Gallery, London, until 18 February 2018 (www.nationalgallery.org.uk)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments