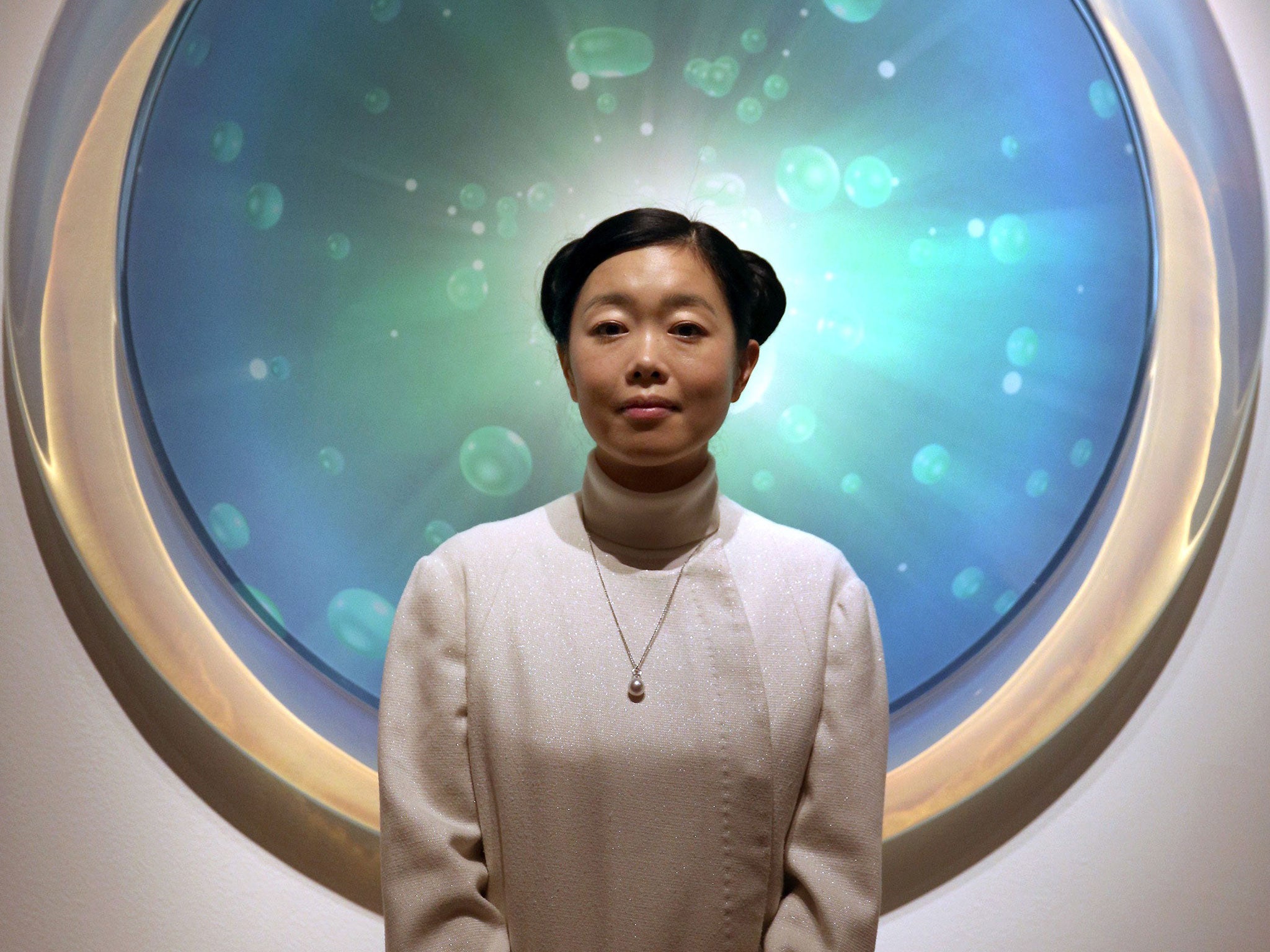

IoS visual art review: Mariko Mori: Rebirth, Royal Academy, London

Mariko Mori's work can be just too lovely. But it will go down a storm in Totnes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.If the Jomon Period is a closed book to you, feel free to share my Googling. The Jomon were Neoliths, which is to say that they didn't use metal or do agriculture much, but they did make clay pots – the earliest, and still among the most beautiful, in the world. The culture died out around the time of the First Punic Wars, when immigrants brought metal-working and rice-farming to Japan. The creation myths of the Japanese are rooted in the Jomon, rather as though our ideas of what it means to be British were based on the builders of Stonehenge.

The weirdness of this last thought is worth bearing in mind if you're planning to visit Rebirth, the Royal Academy's new show of Mariko Mori, a Japanese artist long settled in New York. If it is difficult to picture a British artist tracing her ancestry back to Amesbury, it is at least as hard to imagine her grounding her work in English prehistory. To do so would be to show a seriousness that would make us snigger, the British being at heart a race embarrassed by public displays of intellect. Mori, for her part, is quite at home with the Jomon.

This is not the only difficulty facing Rebirth's British audience: a far graver one is that Mori's work is sincere. Signage in the show tells us that the artist has spent each summer morning of the past 10 years back home in Okinawa, "drawing while looking out at the ocean". Substitute the name "Tracey Emin" for "Mariko Mori" in this sentence and "Margate" for "Okinawa" and you will see the problem. Contemporary British art is allowed to be many things – clever, scabrous, obsessive, scatological, bolshie – but it must on no account be sincere. Even less must it lend itself to the word "spiritual", which Mori's sets out, quite shamelessly, to be.

And then there is the B-word. "Beautiful" is a term of abuse in the contemporary British lexicon, the kind of adjective you apply to an artist's work if you are looking for a punch in the mouth. Mori's is often very beautiful, crafted in materials such as lucite, a sort of acrylic glass that looks like moonstone, and installed in the academy's rooms with a precision that is studiedly Japanese.

Thus, for example, Flat Stone, in which ceramic pebbles like big sugared almonds are arranged around the acrylic cast of a Jomon vase on the floor of a bare white room. Mori is playing with our notions of Japanese-ness, the culture's famed taste for ritual and minimalism. Her installation suggests both a time before – no one knows whether the Jomon were minimalists – and a time after: the white-cube aesthetic of contemporary art galleries is also, by chance, Japanese. Flat Stone is trying to be like Frazer's Golden Bough, finding in things that are apparently specific and insular a set of tendencies that apply to all cultures of all times – "a universal consciousness", as Mori puts it.

But her brush is by no means so narrow. Mori's drawings, shown in a white-walled oval, look faintly cosmological. White-on-white planets float in a space sprinkled with stardust, an uneasy mix of Robert Ryman and Swarovski; the drawings have names such as Higher Being. A room away, Ring – a large (and beautifully made and lit) acrylic hoop, eventually to be hung in front of a waterfall in Brazil – hints at eternity. The flickering lights of Tom Na H-iu II, a vast glass menhir, are driven by impulses beamed from the Institute of Cosmic Ray Research in Tokyo, these marking the death of neutrinos, subatomic particles in turn transmitted by the dying a of star. The work's name is taken from the ancient name for a standing stone circle – not a Japanese word but a Celtic one. Circularity, infinity, omnipresence … you get the message.

So, a confession. I've never been a big fan of Keith Tyson's infinity-machine art, but I found myself longing for it as I walked around this show – for a bit of irony, some cynicism, a dash of absurdity. Mori's work is just too precious, too pretty, too orderly, too damned nice. But there are many people who get it, and it may be that you are one of them. My feeling is that Rebirth is likely to appeal if you do two or more of the following: own a Prius, live in Totnes, go to Findhorn or weave. Otherwise, Mori and her work may annoy you, which you possibly don't need in the lead-up to Christmas. Consider yourself warned.

To 17 February (020-7300 5000)

Critic's Choice

The Godfather of New York avant-garde video art, Jonas Mekas, is showing his film and photographic works at the Serpentine Gallery in London; allow plenty of time as it includes a feature-length film (till 27 Jan). Take a stroll through colour, at Leeds Art Gallery, with Australian artist Nike Savvas's installation-based work, Liberty and Anarchy. The focus is still on fun, with her use of big geometric shapes and colourful ribbons (till 24 Feb).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments