IoS photography review: Light from the Middle East, Victoria & Albert Museum, London

This exhibition is complex, intense and highly charged – portraits of a part of the world where cameras still carry the whiff of transgression

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The single most important cultural fact behind Light from the Middle East is that the representation of the human form is traditionally discouraged in Islamic societies, and under the more extreme Sunni regimes – Saudi Arabia, Afghanistan under the Taliban – that discouragement is closer to a taboo. God created man, so if man represents man he is usurping God's work – that's the view of the hardliners, baldly put.

Belying the strangely simple-minded blurb at the entrance, which begins "Photography is a powerful and persuasive means of expression", the V&A's new exhibition of photography from Afghanistan to Morocco by way of Iran and Palestine is complex, intense, highly charged – in short, a string of improvised explosive devices which shock and stimulate at every turn.

Photography is roughly as old as the experience of colonial oppression in most of these countries: this most potent mode of representation was the gift of the infidels, and one can still detect the whiff of transgression that it must have carried in the early days. That's apparent in Mehraneh Atashi's arresting photo of an Iranian wrestler flexing his muscles in the zurkhana, the traditional gym, under the eyes of the portraits of a whole bevy of ayatollahs, but also under the eyes of the female photographer herself, boldly present where no woman has any business to be, her image caught in a mirror.

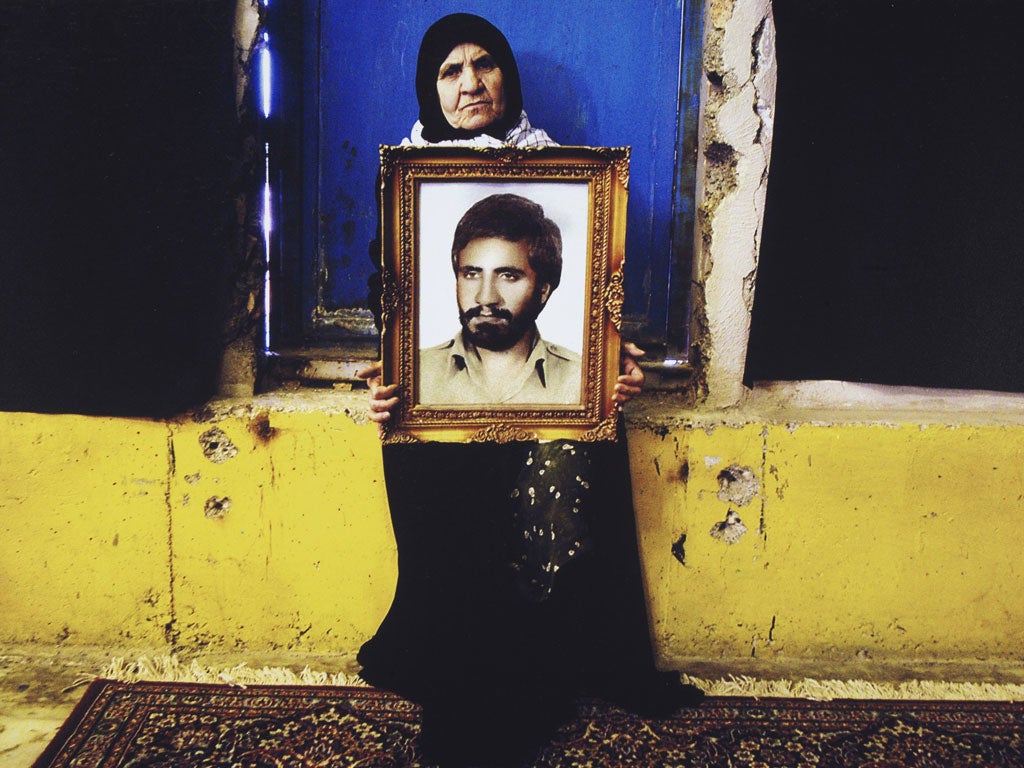

The tension is also there in Abbas's picture from 1979 of Iranian women, indistinguishable one from the other in their black hijabs, examining tiny photos of victims of the Shah's secret police pinned up on a board outside the occupied US Embassy. It's equally present in Taraneh Hemami's Most Wanted in which, shortly after the terror attacks on the US, she downloaded photos of "wanted" Muslims from a US government website, then scratched away at the surface of the prints to erase the facial features. The human face carries a special voltage here: in Newsha Tavakolian's Mothers of Martyrs series, Iranian mothers proudly hold gold-framed photos of their sons, "martyred" in the Iran-Iraq war – and one sees where the Islamic disquiet about icons comes from.

Most of these countries have experienced the modern era as a long series of disasters and humiliations, and the idea of progress in our sense is a sick joke at best. In a large and masterly Iranian photograph – Iranian genius dominates this show – entitled Tehran 2006, Mitra Tabrizian poses ordinary Iranians plodding bleakly about their business in a wasteland in the suburbs of Tehran; the Ayatollah Khomeini gazes down pitilessly from a hoarding. The technological perfection of this huge print is painfully at odds with the stagnant, trackless state of contemporary Iran.

There can be wistful, melancholy humour in these depictions of societies going no place fast: the heap of bricks in Yto Barrada's Bricks seems neither more nor less significant than the ugly block-like villas that dot the exhausted Tangier hillside behind it. In her sepia portraits, Shadi Ghadirian photographs her sitters in the style that was popular during Iran's Qajar period, which ended in 1925, posed glumly in front of vaguely classical backdrops, wearing the inevitable veil – but clasping a Pepsi can, a bicycle, an audio-cassette player. Atiq Rahimi's experience of his native Kabul, when he returned in 2002 after the fall of the Taliban, was too upsetting for humour: two decades of war had reduced his elegant city to ruins. The only way he could bear to shoot it was with the sort of camera he would have used as a child, a Box Brownie. These tiny, fuzzy images are like pages from an old album abandoned as the bombs began to fall.

Not everything here is a success. Syrian Issa Touma's series on an annual Sufi procession in northern Syria, shot over the course of 10 years, may well be an important ethnographical document but fails to capture the intensity of the event. One can guess what Raeda Saadeh was trying to achieve by wrapping her presumably naked body in Palestinian newspapers and posing approximately like a classical European nude, but the effect is unintentionally comic.

Mutely powerful, by contrast, is the other Palestinian contribution, by Taysir Batniji: a series of identical portraits of the watchtowers built by Israel to oversee the Palestinians penned into their Territories. The variable quality of the resulting pictures was because Batniji, resident in Gaza, was forbidden to visit the West Bank to shoot the rest of the series and had to delegate the job. That says almost as much about the subject as the pictures themselves.

Until 7 April (020-7942 2000)

Critic's Choice

In a single year, modern art took several leaps forward, thanks to Archipenko, di Chirico, Picasso, Duchamp and others. Their works, some influenced by earlier iconoclasts such as Matisse and created on the eve of the First World War, are brought together in 1913: The Shape of Time at the Henry Moore Institute, Leeds (to 7 Feb).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments