Henry Moore: Late Large Forms, Gagosian Britannia Street, London

Gigantic bronze sculptures that fight for attention in public squares get a quiet place of their own

What is bronze, and what does it mean? To Henry Moore, as to most sculptors, the answer was more complex than an alloy of copper and tin.

When Moore's contemporary, Barbara Hepworth, turned to large-scale bronze sculpture late in life, she had to sell one of her most valued possessions – a Mondrian, given to her in the Thirties by the artist himself – to pay for it. More even than marble, bronze has been seen by sculptors as a sign of having arrived. Moore beat Hepworth to big bronzes by 20 years, moving into the monumental scale we nowadays associate with his name. But was this entirely the triumph it sounds?

The question hangs over a fascinating show, Henry Moore: Late Large Forms, at the Gagosian Gallery in London. In 1948, at the first Venice Biennale after the war, Moore took the Grand Prize for Sculpture. His work was shown alongside Turner's, a pairing the Yorkshireman modestly described as "very sensible". After that, the world and its piazzas were his oyster.

By the time of the works in the Gagosian's show – 1960 to 1980 – Moore's big bronzes were everywhere. His triumph in Venice had coincided with the passing, back home, of the New Towns Act: there were Moores in the civic centres of Harlow and Stevenage. At the other end of the political scale, they sprang up in squares outside city halls and banks in Kansas City and Toronto, Chicago, Dallas and New York. Soon, their ubiquity came to be held against them. In 1978, the American architect James Wines coined the phrase "turd-in-the-plaza" to describe a certain kind of default public sculpture. There was little doubt whose he had in mind.

And that is where Moore has stuck in the public consciousness, as the maker of great big bronzes which are there to be walked past or sat on but not to be looked at. How to get around this? The Gagosian's answer – "very sensible", as Moore might have said – is to show his large-scale late bronzes indoors.

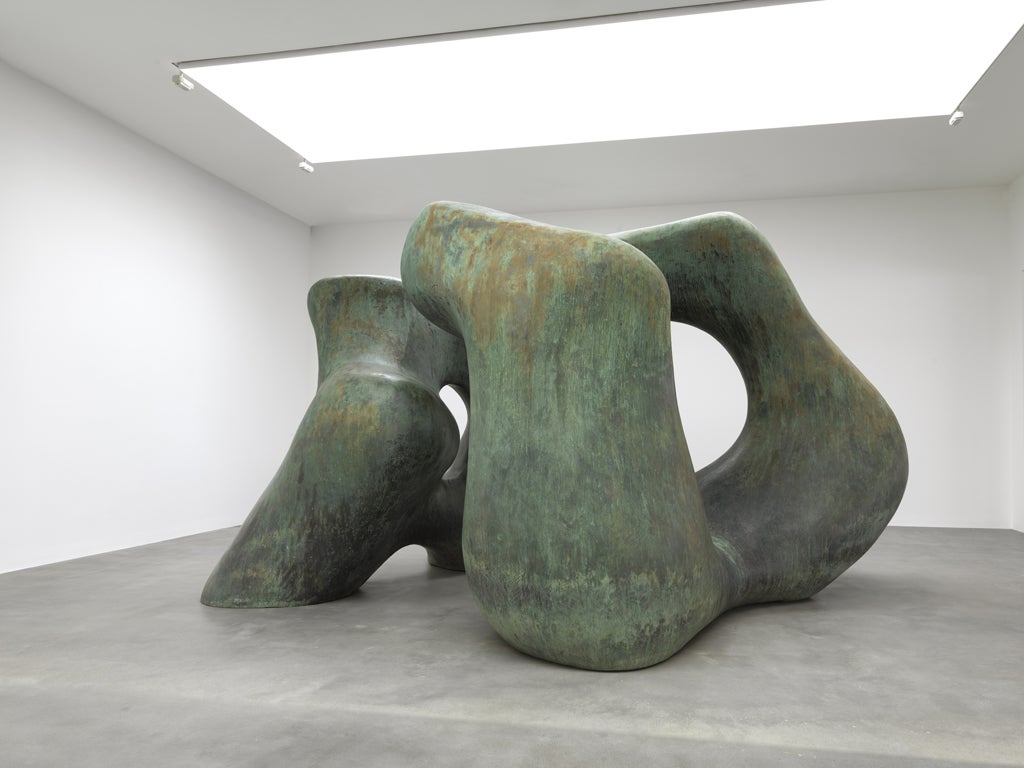

What is bronze? The answer, to Moore, was many things. In a room to the right as you walk in are Two Piece Reclining Figure No 2 (1960) and Large Four Piece Reclining Figure (1972-73). The newer, bigger work is smooth and highly polished, like a Brancusi of 50 years before; the smaller and earlier is rough, black and cloacal, made to look like an outsized clay maquette. In the next room is another variation on the theme of bronze, the vast Large Two Forms of 1966. Now the metal is matt, covered in green verdigris induced by the Wakefield rain. (The piece has been lent by the Yorkshire Sculpture Park.) As well as the water stains running down it, the hole in the smaller of the work's two parts has been polished by generations of children climbing through it.

All of which prompts a number of questions. It is undeniably jarring to see these works indoors, not least because of the unlikeliness of their being there. It takes vast spaces and vaster budgets to do what the Gagosian has done. But then these works were not made to be seen inside. Museums recontextualise things all the time, unavoidably: what Renaissance altarpiece was ever made to be shown in the National Gallery? Here, though, it is done with a specific agenda.

The hope is that seeing Moore out of context will be to see him afresh – put crudely, that taking the turd out of the plaza will de-turdify it. Walking around Three Piece Sculpture: Vertebrae (1968) in the Gagosian is quite a different experience from walking around it in the garden of the sculptor's old house in Hertfordshire, or in Jerusalem or Seattle where there are other examples of the same piece. The sightlines are shorter, the element of accident is lost; the sculpture exists by itself, with no back-and-forth between it and its setting. But do we gain anything from seeing Moore's public work in this private way, in an aseptic white space?

Here, too, there are many answers. One is that the Henry Moore who emerges from Gagosian's show is sometimes classical and sometimes just old-fashioned, often very good (Three Piece Sculpture) and occasionally rather bad (Reclining Connected Forms). You can't help feeling that success, so eloquently summed up in the word "bronze", was also a kind of failure for him, that the variants Moore found for the word – black, matt, shiny, green, rough, smooth, etched – represent a struggle against it. The main thing, though, is that we see Moore at all; that his work, so long made invisible by its visibility, is held right in front of our eyes.

To 18 Aug (020-7841 9960)

Critic's Choice

Painting, drawing, photography, sculpture and textiles from West African artists are at the heart of a city-wide exhibition opening this weekend in Manchester (to 16 Sep). The City and Whitworth art galleries, Manchester Museum, and the Gallery of Costume explore the links between Manchester and West Africa, in We Face Forward, part of the Cultural Olympiad.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies