Hanne Darboven, Camden Arts Centre, London

The meticulous but empty management of Hanne Darboven makes us think about our need to parcel up our days

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Were you to start your visit to the Camden Arts Centre's new show in the gallery's study room, you might come away with entirely the wrong idea about Hanne Darboven.

In a vitrine in the room are, in no particular order, a mini-violin in its case, a box of small pencils (the brand called Rubens, the pencils faded pink), a desk calendar from 1976, another, outsize pencil made from a cardboard poster tube, and a roll-up case containing a vast number of crayons. Knowing that Darboven was German, the words to spring to mind might be "Joseph" and "Beuys". Beuys was the arch-vitrinist, after all, and these objects have the self-mythologising feel of his work. That Darboven has nothing to do with Beuys becomes clear as you walk into the next room.

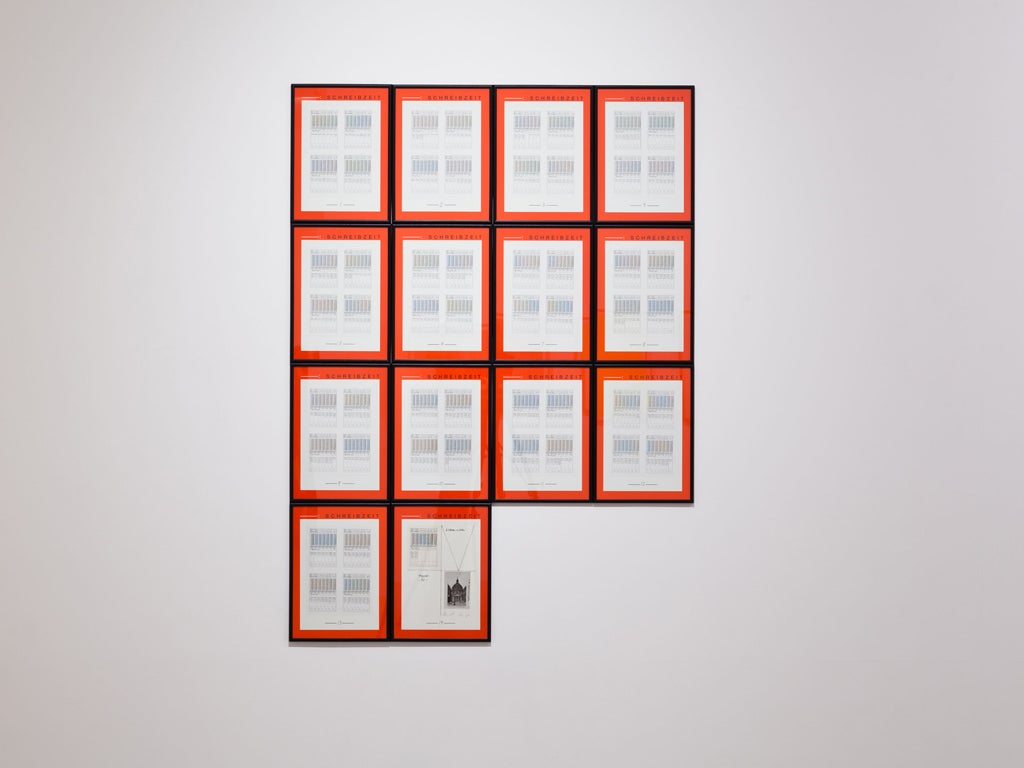

Hanging on the left wall as you enter Gallery 1 is a piece by Darboven called Weltansichten, ("Visions of the World"). This consists of 14 rectangular works, each framed and hung in a tight grid, four by four but with the right-hand columns missing the bottom parts. Each individual work consists of a white print on a red mount, each print being of four pages from a diary, also arranged in a portrait-format grid, two up, two down. Each red mount is labelled Schreibzeit – "writing time" – while each page-print bears the triple legend Stundenplan, Tagbuch and Wochenplan, hour-, day- and week- planner. Each line of each page has been filled in – the jottings of an excessively meticulous author, you might think, until you go to read the words and find that they are scrawls, blah blah blah blah blah.

All that order, all that organising, for nothing. Not only has Darboven gone to the trouble of choosing just the right card and paper, she has had each sheet printed in two different ways, silkscreen and offset, and then framed and hung. As you stand in front of Weltansichten, you are suddenly aware of time – not just the kind marked by diaries and Stunden, Tagen and Wochen, but of the time it takes to make time, the time-consuming business of inventing it.

Rather than Joseph Beuys, the artist you might find yourself thinking of as you look at Darboven's work is Samuel Beckett. Like the tramps in Waiting for Godot, there seems to be something tragicomic, or maybe absurd, about this pointless time-killing. But that is not quite right, either. Actually, Weltansichten feels less a defeat than a triumph, its meticulousness poised and beautiful. It is as though Darboven has taken the visual nuts and bolts of timekeeping – the addings-up and takings away, the algebraic scribbles – and moulded them into a chronology of her own.

That sense of a new system, of a system beyond systems, is stronger still in 9 x 11 = 99, whose 99 cells or frames are divided into five unequal grids which look, from across the room, as if they might be runic letters that spell out a word. It is there, too, in Appointment Diary, in which the various pages of the American Film Institute desk diary for 1985 have been opened, photographed, mounted and framed in a room-sized installation of 74 parts. Some of the spreads have stills from classic films on the right and blank diary pages on the left, some the other way about; others are double blank pages or double photos. Seen all together, these endless permutations of blank/no-blank seem like a kind of language – of semaphore, perhaps, readable in the way that naval signalling flags are readable.

It is a commonplace of art criticism to describe abstract works (Mondrian's Boogie-Woogies, say) in terms of music, as though they were a visual translation of harmony and counterpoint. That is usually a mistake, and certainly would be in the case of Hanne Darboven. That she studied the piano before she studied art, and that the titular songs in 24 Gesänge (24 Songs) are both written down in a notation of Darboven's own inventing and played on a cathedral organ is, in a sense, a red herring. What the Gesänge do is to take another system into another medium, to exult once again in the beauty and oddity of man's need to define. The cross-dressing Darboven, dead three years ago at the age of 69, was an extraordinary woman, her house filled with junk, her works, when its walls were full, hung on the ceiling. Some of these she ascribed to her pet sheep, Mama Micky and Klein Micky. As you'd expect, this is an extraordinary show. See it, and hear it, if you possibly can.

To 18 March (020-7472 5500)

Next Week:

Charles Darwent sees David Shrigley at the Hayward Gallery

Art Choice

The artistic influence of arrivals to Britain from Van Dyck to John Singer Sargent and Naum Gabo is celebrated in a new show, Migrations, at Tate Britain (Tue to 15 Aug). Today is the last chance to see the exhibition dedicated to Adolphe Valette, the Impressionist whose vision of Manchester captivated his pupil L S Lowry (Lowry Galleries, Salford).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments