Everything Was Moving: Photography from the 60s and 70s, Barbican, London

A collection of photos from across the globe offers a rare opportunity to reflect on two decades of revolution, war and social change

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Everything was moving – but where was it going? At the Barbican, curator Kate Bush gives us a snapshot of an exploding world just as the thing begins to blow. You can almost hear the sound of ripping. A few years later it would be possible for Francis Fukuyama to announce the End of History. But the world of the 1960s and 1970s was a moment of yang, not yin, of irresistible centrifugal force, as the certainties of simpler times were torn apart.

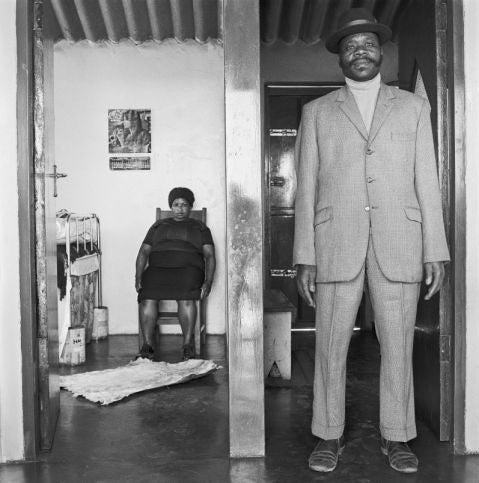

This is clearest downstairs in the exhibition, where two great South African photographers bear witness to the apartheid state. David Goldblatt, safely on the white side, coolly records the chafing, riving contradictions of a system rooted in systematic injustice. We see the Afrikaners still in the saddle, the hatchet-faced National Party commandos escorting prime minister Verwoerd to the party's 50th anniversary celebrations, the farmers and their children innocently at play on their endless properties. And we see what underpins that tranquil state: the evening exodus from Johannesburg, whites in their cars headed one way, massed blacks on foot going another, the miners' windowless concrete bunks at a gold mine, the smoky Soweto hillside covered in identical hovels.

Then the black photographer Ernest Cole takes us right inside: the jam-packed trains, the same bunks now heaving with miners, police swooping on blacks to enforce the hated pass laws, a gang of blacks mugging whites on Johannesburg streets – black and white not separate at all, as state dogma insisted, but forced together like the components of a bomb.

In the same years on the other side of the Atlantic Bruce Davidson recorded the controlled explosion of the civil-rights movement: whites in Alabama grimace and taunt the passing Freedom Riders, a white woman in a New York drugstore scowls at having to share the counter with a black, Klansmen circle a flaming cross; but all the while the blacks are calmly implacable, whether hauled off to jail by their feet, listening to Malcolm X in New York or marching with Martin Luther King on Montgomery's State Capitol.

Of course, we cannot avoid looking at this work with the wisdom of hindsight: we know what happened next. This also conditions the way we regard the Vietnam war photographs of Larry Burrows, and there is some curatorial sleight of hand in presenting the work of "rather a hawk" (as Burrows described himself) as if they were stills from Apocalypse Now. At the time, Life magazine was happy to run them in heroic mode, these images of suffering GIs holding back the commie horde.

What the United States was doing to Vietnam it had done 20 years before to Japan, and Shomei Tomatsu, the "godfather" of modern Japanese photography, cannot tear himself away from the feelings of estrangement and humiliation that were the occupiers' gifts, along with their chewing gum and chocolate. But abuse and domination is not the end of the story, because in Tomatsu's work along with those ugly emotions there is the exhilarating, vertiginous sense of breaking out into a strange new world. Authenticity is the photographer's holy grail. For centuries, Japanese artists had refined a particular stylised vision which excluded the rest of the world as rigorously as the shoguns barred access to their ports. Now at last, in these ranks of riot police and in the protester flying through the air, here was something real, however dark or feverish or painful.

Authenticity was harder to pin down in the US, the heart of the new imperium, where the persuasive arts had been taken to new heights. Back then, photographers proved their sincerity by putting on the sackcloth of black and white: to shoot colour was to go over to the other side. It took the cussedness of William Eggleston to challenge the advertisers at their own game, recording in lush, full-spectrum Kodachrome the cadmium green of a diner's banquette, the cobalt blue and two-tone tyres of a new car, the slick, super-abundant stuff of the first fully homogenised industrial economy. If the world was exploding, here was the detonator. But these images are cool and still and affectless: Eggleston records the effort to charm and to sell, but remains completely unimpressed, and gives the rust and discarded cans and festering rubbish just as much of his icy attention as the material of the Dream. The sun-drenched woman at the wheel of her sedan catches the photographer's eye, but it doesn't mean anything. And, up above, the American sky is huge and indifferent.

To 13 Jan (020-7638 8891)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments