David Shrigley: Brain Activity, Hayward Gallery, London

The master of whimsy wears his art-school credentials on his sleeve, but his ideas feel derivative and the jokes wear thin

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Even more than any of his contemporaries, David Shrigley forces us to ask the Big Question: is it art? Shrigley, 43, is best known for his newspaper cartoons – scratchy, naively drawn figures in black and white, usually with a deadpan legend attached. One that sticks in the mind, for some reason, is a pig with the words “I’m a pig” written on its side. It is not particularly funny, but then nor is it meant to be. Shrigley’s drawings have a higher aim than that. Their maker went to art school, ergo they are art.

Or are they? To answer that question, it might help to mull over the range of the word “conceptualism” as you walk around Shrigley’s new show at the Hayward Gallery. Jeremy Deller, his more-or-less exact contemporary, conceptualises on a grand scale. Deller’s re-enactments of miners’ strikes and brass band ensembles are vast in scale and call for the participation of dozens – sometimes hundreds – of people. (A retrospective of his work will open downstairs from Shrigley’s on 22 February.) By contrast, Martin Creed makes his art out of almost nothing – a light bulb going on and off, new marble cladding on a stairwell, someone running in a gallery. Creed’s work is so reticent that it seems scarcely to exist. Shrigley’s takes this tendency a step further by suggesting that it may not be art at all.

If you want to ponder this comparison, then start with Light Switch (2007), an animated cartoon by Shrigley in which a finger flicks a light switch on and off. With each flick, the projector showing the cartoon lights up or dims. The piece is, presumably, meant as a take on Creed’s notoriously Turner-prize-winning Work No. 227, although whether it is, as the catalogue holds, “an affectionate nod” or something sharper is hard to say.

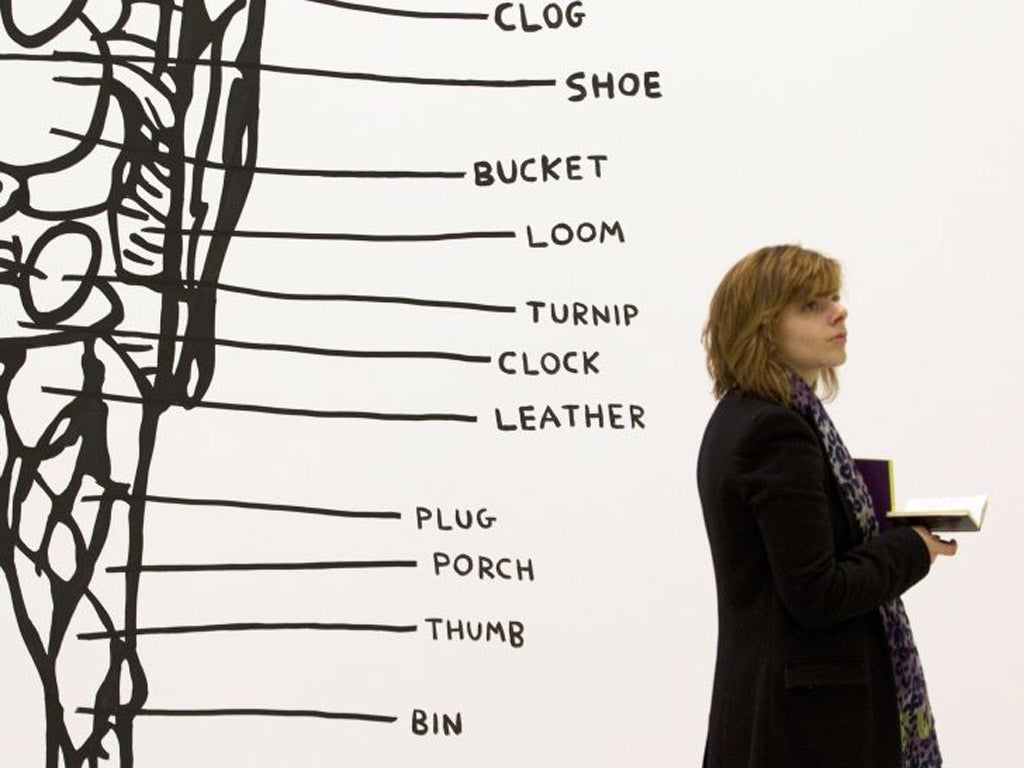

Creed is not the only subject of Shrigley’s ambiguous homage. The misspellings, crossings-out and childish hand of his cartoons has the feel of Tracey Emin; a crumbling molar called What Decay Looks Like, and an anatomical diagram in which the organs have been renamed – the heart is labelled “clog”, the willy “chimney” – seem to be aimed squarely at Damien Hirst. Another animation, of a Shrigley stick-man tucked up in bed and snoring, is some kind of play on AndyWarhol’s Sleep. The question in all these is of tone of voice – of what Shrigley thinks about contemporary art.

It is, on the other hand, a big question, and one with no clear answer. A surprising thing about this show is the breadth of David Shrigley’s practice. It is easy to think of him as a one-trick pony, a maker of gnomic cartoons. One wall of one room is given over to these. For the rest, the Hayward’s show is made up of works that seem, at first glance, oddly un-Shrigley-ish.

Among much else, there is a staircase-shaped plinth holding a dozen pairs of ceramic wellington boots; a taxidermised Jack Russell holding a placard that says I’M DEAD; a tiny couple, fashioned from bits of a hat-stand, having missionary sex on the bonnet of a car; a vitrine containing what look like the relics of a martyred saint; and a dozen or so broadswords and dirks, hung in a circle as on the wall of a Scottish Berni Inn. There is a gridded metal door, wrought with the legend “Do not linger by the gate”, through which visitors must pass to get from one room to another. Outside, on the Hayward’s riverside terrace, is a word-sculpture that spells out the message LOOK AT THIS.

As with the show’s subtitle – Brain Activity – the last of these points to the playing of some kind of clever game. Look At This is title and object, cause and effect; in structuralist terms, it is signifier and signified. Shrigley’s message, oblique and easily overlooked, is nonetheless clear. I have been to art school, it says. Dismiss me at your peril.

This is interesting enough as far as it goes; the trouble is, it doesn’t go very far. For all his branching out into molars/broadswords/ copulating couples/ceramic wellies, Shrigley never really gets away from being a cartoonist. Each work is a one-liner, and the line is always the same: Am I anything more than I seem? As you walk around his Hayward show, you have the sense of being gently played with. This is engaging at the beginning, but the novelty soon wears off. By the time you get to the headless ostrich – no brain activity there – it is all rather annoying. I should wait until Deller’s show opens before visiting the Hayward.

To 13 May (020-7960 4200)

Next Week

Charles Darwent comes face to face with Lucian Freud at the National Portrait Gallery

Art Choice

Hanne Darboven brings her systematically beautiful work to London’s Camden Arts Centre (to 18 Mar). Alternatively, you can get lost in the woods with David Hockney RA: A Bigger Picture, which brings together his paintings, and iPad prints, of Yorkshire landscape at the Royal Academy (to 9 Apr).

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments