Charles Darwent on art: Paul Nash, The Clare Neilson Gift - A modernist moment in the sun, and retreat to the shade

Like many British artists, Paul Nash was drawn to Paris but felt impelled to play safe at home

A small image in a small show: a woodblock print, an inch and a half by three, by Paul Nash. The engraving is in a slim volume of verse, A Song about Tsar Ivan Vasilyevitch, by the Russian poet Mikhail Lermontov. It is in Gothic type on Japan paper – the kind of literary objet de luxe turned out in its day by small publishing houses with names such as The Golden Cockerel Press. This one is by The Fleuron. Everything about the book says "Arts and Crafts" and "1869". The label, though, says "1929".

Everything about the book looks 60 years out of date, that is, except Nash's wood engraving. That is definitely of its time. It is not a pictorial illustration of Cossacks and boyars, but an abstract composition of triangles and rhomboids. It is deeply un-English.

Little bat-squeaks of abstraction in the work of the Vorticists apart, artists on this side of the Channel had shunned abstract painting as something foreign and thus probably immoral. By 1929, the date of the print we're looking at, Mondrian had been painting his red-blue-yellow grids for a decade and Russian abstractionists were well enough established to be on the point of being banned by Stalin. Nothing of this had shown up in the studios of London, though. The hottest thing around was Christopher Wood, who had been to art school in Paris. You might not have guessed it from works such as Porthmeor Beach and Dancing Sailors.

Nor would you have learnt much about abstraction from the paintings of Paul Nash. In the same year as Nash made this small wood engraving, he painted Tate Britain's Landscape at Iden. The trees in that image are thought to echo those of the battlefields he had seen as a war artist in France. If Nash's work is bothered by the past, though, it is also haunted by the future. To the right of the composition is what looks like a Modernist grid. Closer inspection shows this to be a willow windbreak, a Mondrian turned into a little piece of Old England.

But then there is this wood engraving. It is in a show of Nash's work at Pallant House in Chichester, of a bequest made through the Art Fund. The collection was put together over 30 years by Nash's close friend, Clare Neilson. It is an intimate gathering of small-scale objects, including letters, photographs, books and other works on paper. It shows a different Nash from the one we're used to, the painter of flints and copses, of British trenches and, later, of German bombers. But what Nash does it show? English artists of the inter-war years may have been insular, but they were not ignorant. Like Ben Nicholson and the rest, Nash had seen the Continental art magazines passed from hand to hand in London.

In 1930, he made the compulsory pilgrimage to Paris, as would Nicholson and Hepworth, John Piper and Henry Moore. Tate Britain's Kinetic Feature of 1931 shows Nash's response to what he saw there. He was thought of, in England, as the most abstract of his contemporaries, although seeing Kinetic Feature next to a Tate Mondrian may suggest why comparisons are odious.

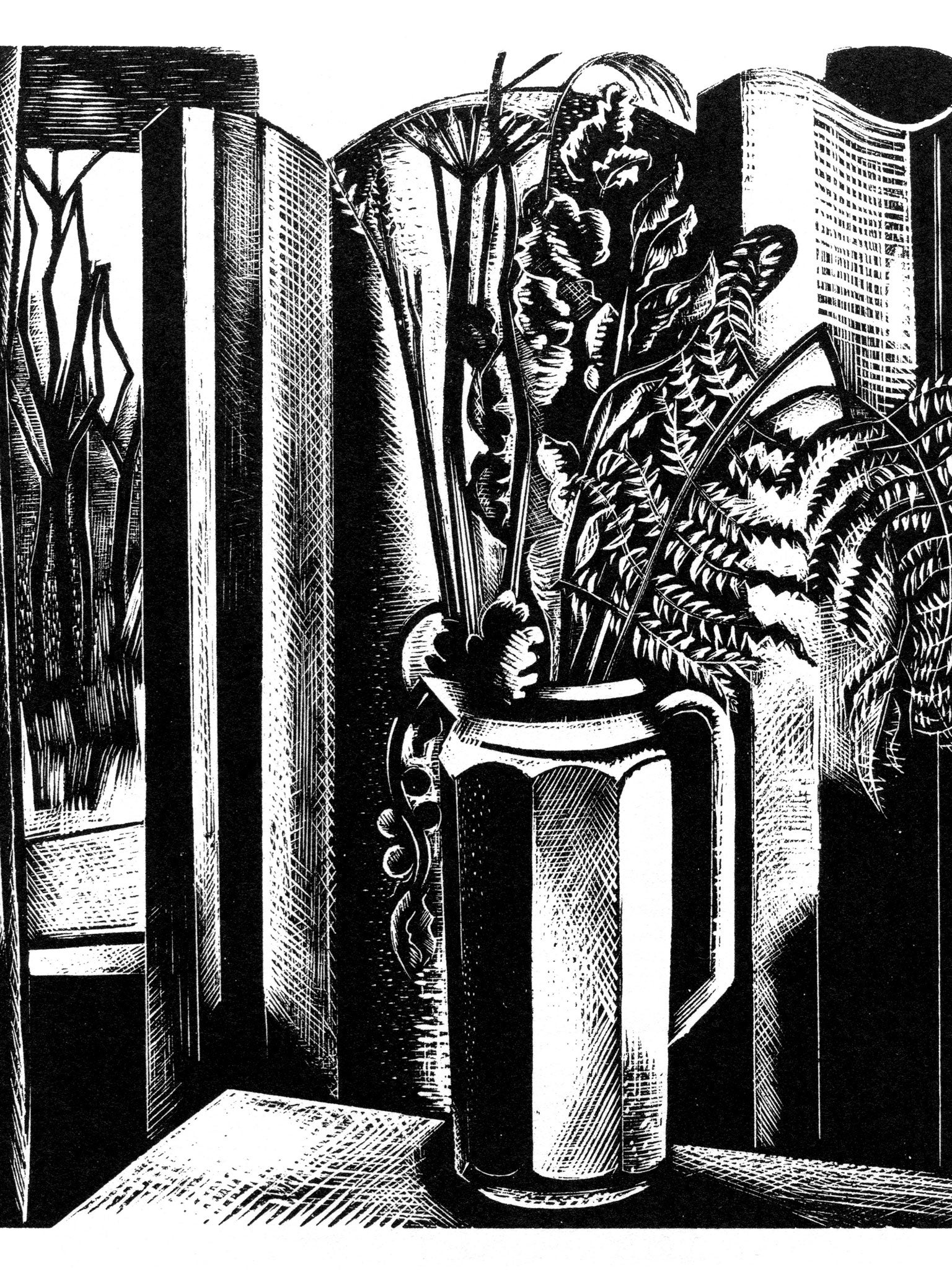

But here, for a moment, Paul Nash is genuinely abstract. How come? Two years earlier, in 1927, he had made another small print, Still Life #2. This, of a vase of flowers, is deeply un-avant garde, very English, very Nash. Perhaps he felt that the audience for Tsar Ivan would be sophisticated, the kind that read foreign poems. And Lermontov's being Russian may have given him the space to work like one himself; like Malevich, say. Nash was not immune to the charms of abstraction – his 1936 leather binding for Signature magazine shows that – but he knew his market. Abstraction was fine for poetry books and typography magazines, but it wasn't going to wash on canvas. John Piper found that out the hard way in the mid-1930s, before going back to painting moody castles and stately homes.

As often with a small exhibition, and particularly at Pallant House, the glimpses afforded are oddly revealing. This one evokes not just Nash but his moment in English art history; a depressing moment, to my mind, but an excellent evocation of it.

To 30 June (01243 774557)

Critic's Choice

Barocci: Brilliance and Grace at the National Gallery in London shows the Renaissance artist's altarpiece and paintings outside Italy for the first time (till 19 May). Italian masters get a good airing outside London too, with Bellini, Botticelli, Titian … 500 years of Italian Art at Warwickshire's Compton Verney gallery (till 2 Jun). 40 very fine, newly cleaned paintings from 1400 to 1900, taken from the civic collections in Glasgow, complement the gallery's own Neapolitian Collection.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies