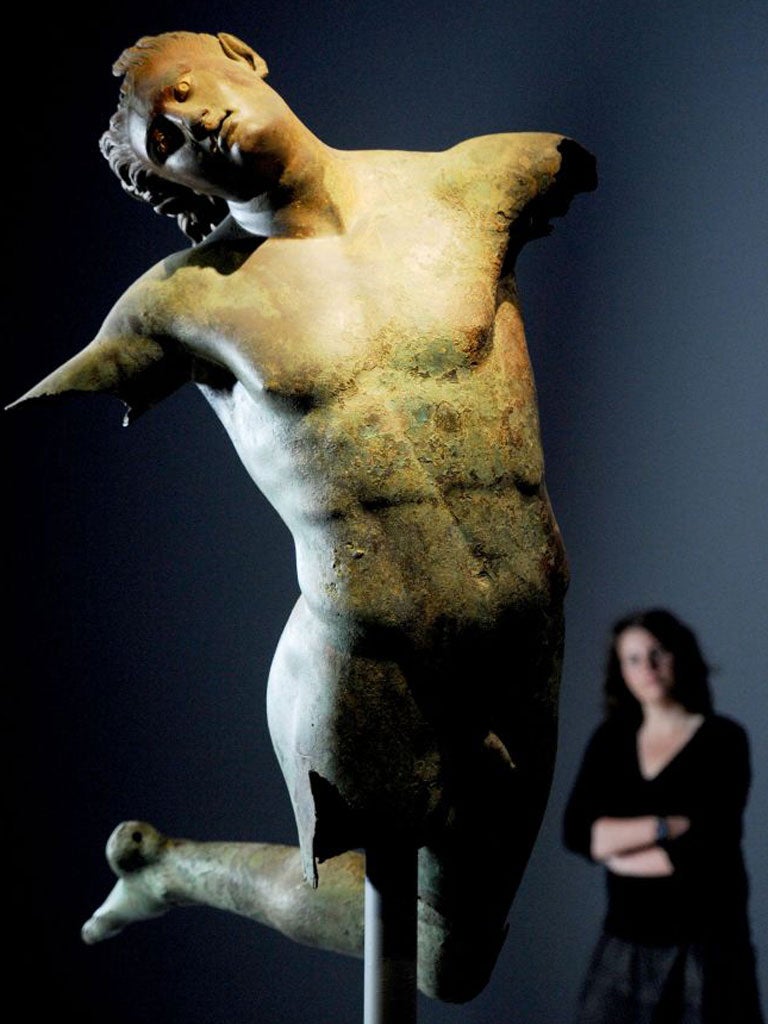

Bronze, Royal Academy, London

Artists from antiquity to Jeff Koons show why we revere bronze as the material of the gods

What to say about Bronze or, come to that, about bronze? The first is a show of the second – a massive, magnificent bringing-together at the Royal Academy of 150-odd metal objects spanning three continents and 5,000 years.

It seems hardly credible that some of them should be here. How do you go about borrowing Giovan Francesco Rustici's three-part St John the Baptist Preaching to a Levite and a Pharisee? How do you get a life-size, 19th-century copy of Cellini's Perseus with the Head of Medusa – one of the biggest single-cast bronze objects ever made – into Burlington House? Bronze is a stupendous achievement, little short of a miracle. And it is annoying.

Take the works above. Both were made in Florence, in what is now unfashionably called the High Renaissance: St John cast towards the end of 1509, when the Medici were in exile, Perseus in 1545 when they were back in power. That both works are in bronze is hugely significant. Working in an alloy of copper and tin was certainly not a new idea in the 1500s, the Bronze Age in Europe having kicked off in the mid-fourth millennium BC. The antiquity Cellini and Rustici were interested in was more recent, though.

Across from their bronzes is another, Roman; a slightly more-than-life-size portrait of Lucius Mammius Maximus, a big cheese in Herculaneum at the time of the Emperor Claudius. By working in bronze, the Florentines were establishing their city's descent from Rome, Republican or Imperial depending on whether the Medici were in or out of town. These particular statements of civic lineage were large and public, but they could equally have been small and private: witness Donatello's delightful Putto with Tambourine in the same room, or Desiderio di Firenze's exceptionally rude Satyr and Satyress in a room labelled Objects.

All of which is to say that, even in the same place and at the same time, bronze could be many things: big, small, public, private, moral, immoral. In purely material terms, that was its point: it was adaptable and durable. But, for Cellini and the rest, it was also charged with a specific historic meaning. So, in a very different way, was it for Jeff Koons.

Again in the Objects section is Koons's Basketball, made in 1985 when the artist turned 30. The piece is typically clever, and typically enigmatic. Although brazenly just what it says it is, Basketball has the platonic beauty of Boullée's Cenotaph for Isaac Newton. And, like Perseus, it is bronze for a reason. Postmodern cheekiness apart, Koons picks up on the material's longstanding use in memorial sculpture. Basketball mourns his own lost youth, the hanging up of the artist's hoops.

These are easy enough connections to make, and perhaps even interesting ones. So why doesn't Bronze make them? Organised by type of object – Animals, Groups, Figures, et cetera – the show seems to want to tell us something like this: Artists of antiquity worked in bronze, and so do modern ones; Nigerians do it, and Indians, Tibetans, Greeks and Americans. To which you can only say: well, yes.

The problem is that Bronze is both too focused and not focused enough. In the second category comes the inclusion of Anish Kapoor's concave wall piece, Untitled, which is, strictly speaking, in polished copper and has little to do with anything much else in the show. I'm not sure about the gilded Chinese Hevajra, either, since its bronze is only there as a vector for something shinier and more expensive.

More problematic, though, is the show's lack of narrative. What we are presented with, in the end, is a great many bronze objects. That these illustrate a vast variation in time, place and intent is secondary, for the curators' purposes, to the fact that they are all made of the same material. To emphasise that sameness, they are all lit in the same way, by a single spot from above. Differences between the objects are thus, if you will excuse the metallic mixed metaphor, ironed out.

This is not a good thing. As a sign at the entrance to the show points out, "Bronze is uniquely suited to …capturing the fall of light". Durability apart, the alloy's oily, sexual quality has, surely, been the main reason for its universal aesthetic appeal. Subjecting the stupendous things here to this ve-heff-vays-off-making-you-talk treatment does them, and the material of which they are made, no favours at all. To pick an object at random, the astonishing Etruscan Chimaera of Arezzo, top-lit, becomes two-dimensional and lifeless. At least you can walk around the poor beast, which is not true of 90 per cent of the works in this show. Sculpture needs to be walked around. What is the point of seeing Barbara Hepworth's Curved Form (Trevalgan) in a vitrine against a wall?

But these are annoyances rather than disasters. Any one of the works mentioned above would have made Bronze worth visiting. Together, they make it unmissable. So don't miss it.

'Bronze' (020 7300 8000) to 9 Dec

Critic's choice

Visit London's Hayward Gallery for Art of Change: New Directions from China, featuring nine artists who have been working for 30 years on installations and live work (to 9 Dec). At Tate Liverpool, three giants of 20th- and 21st-century painting show that some people really do keep the best till last. Turner Monet Twombly is at Tate's Albert Dock home until 28 Oct.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies