Art review: The Male Nude, The Wallace Collection, London

The male nudes in the Wallace Collection’s new exhibition display a painstaking proficiency, but they’re unlikely to arouse much passion, says Adrian Hamilton

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In pictures of the Royal Academy’s life classes in the 18th century you can often see an hourglass. It was used to determine how long the poor models could be expected to hold their stance before stopping. Looking at the drawings of the male nude in the Wallace Collection’s exhibition of 18th-century drawings from the Paris Academy you can see why. Contorted into shapes of agonised pain, draped upside down over rocks and fixed in position of outstretched arms and tautened limbs, the poor underpaid men – mostly recruited from the military – must have been ready for collapse by the time their two-hour session was up, however helpfully a rope or back support was provided.

Drawing from life was made the fundament of the Paris Royal Academy of Painting and Sculpture founded by Louis XIV in 1648. First you started drawing the human form from sculptures, then you moved to life classes. It was men only, of course, both in the classroom and for models. If you wanted to draw or paint female nudes, you had to do that in the studio of the artist to whom you were apprenticed or in your own rooms with women you could pick up from the street. The result, as the 37 drawings tastefully displayed in two rooms of the Wallace Collection illustrate, was to produce the highest standards of proficiency in graphic modelling of the male body.

It’s all very French in its deliberateness and precision. The British Royal Academy, founded by George III more than a century later, copied the French emphasis on life drawing, but with a rather looser if not occasionally lascivious spirit. The French would have none of that amateurish approach. This was a professional training and students were required to reach the highest standards of graphic skill. You were only allowed in on the recommendation of an Academician. Sons of Academicians had the front row (there could be 150 in a session), prize winners processed before the rest.

Being French, of course, practice had to conform with philosophy. Where the great Renaissance masters such as Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer copied nature as it appeared before them, and people as they observed them in real life, French theory at the end of the 17th century elevated the idea of an “ideal” or “perfect” nature which artists should seek behind the real thing.

As a means of capturing this ideal they insisted, as later did the Italians and the British, that the study of the models of antiquity, seen mostly in plaster casts of the marble statuary of Greece and Rome, form a basic part of their courses. The Apollo of Belvedere and the tortured death throes of Laocoön were the most copied and the most inspected artistic imagery of their day. You couldn’t be a trained artist of the day without knowing every twist of the body and ripple of muscle of the ancients.

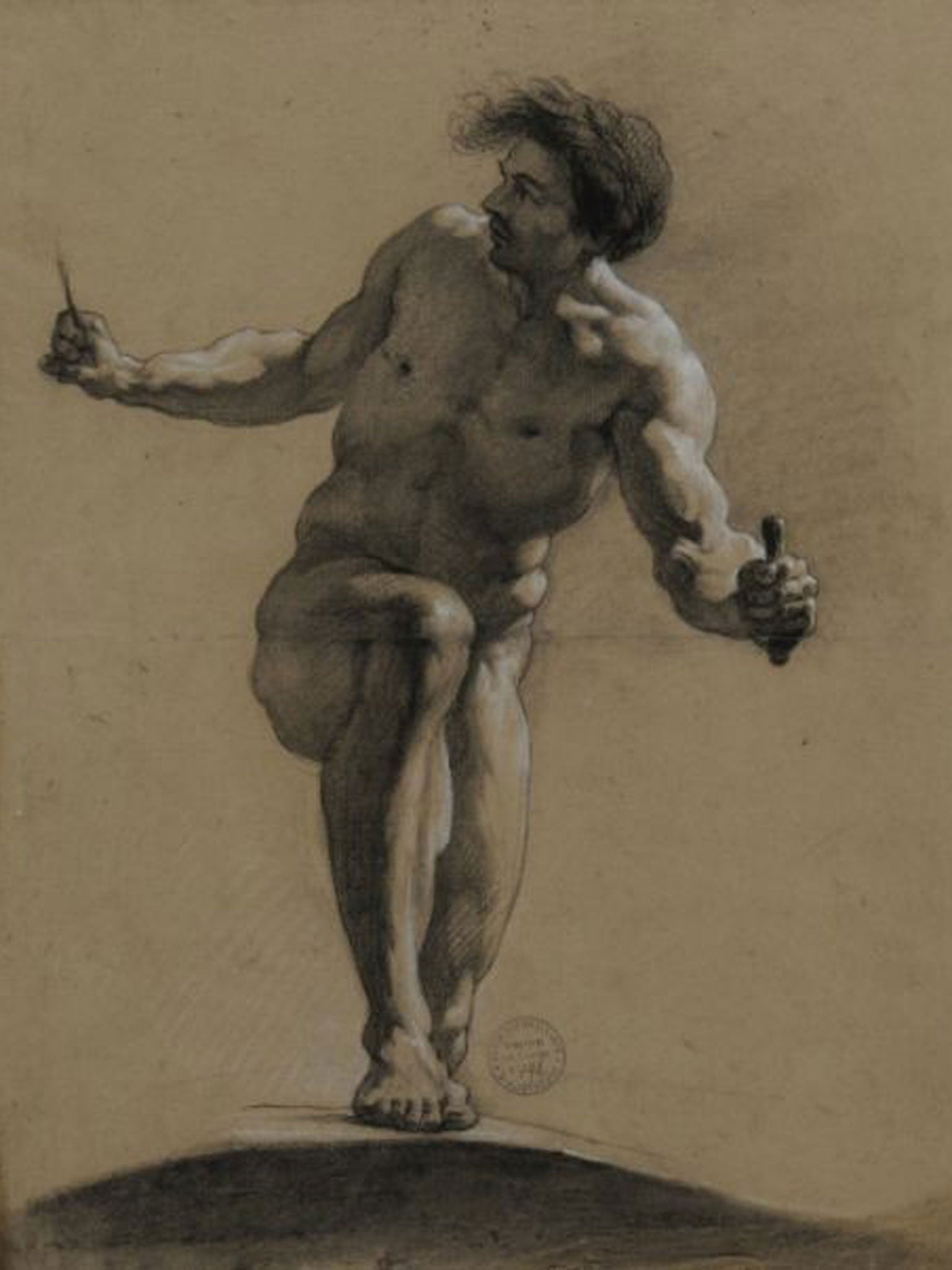

If all that gives an impression of artifice (Diderot hated it in his quest for untutored nature) there’s no doubting the skill instilled in the students. Drawn in black and red chalk, highlighted in white and often using stumps of rolled paper, the drawings together create a rich sense of muscular manhood in action or repose. Some of the drawings on display are by teachers, others by students, although you’ll need the catalogue to decide which is which.

The exhibition helpfully gives several examples of the same stance being drawn by several different artists, dismissing with lordly contempt (and I thought a little unfairly) the efforts of an A. Belin to depict a “Man lying down with raised legs” done in 1762 in comparison with his peers and providing no less than four separate versions of a “Standing man, turning towards his right”, a comparison in which Claude Chailly’s version would seem to win not least because it is taken from the front rather than the back.

All these versions of rippling pecs, bulging biceps and muscled backs are unlikely to arouse excessive salivation from either male or female viewers. Indeed, the drawings are remarkable for how shy they are of showing the male genitalia in anything other than the vaguest of small sacks.

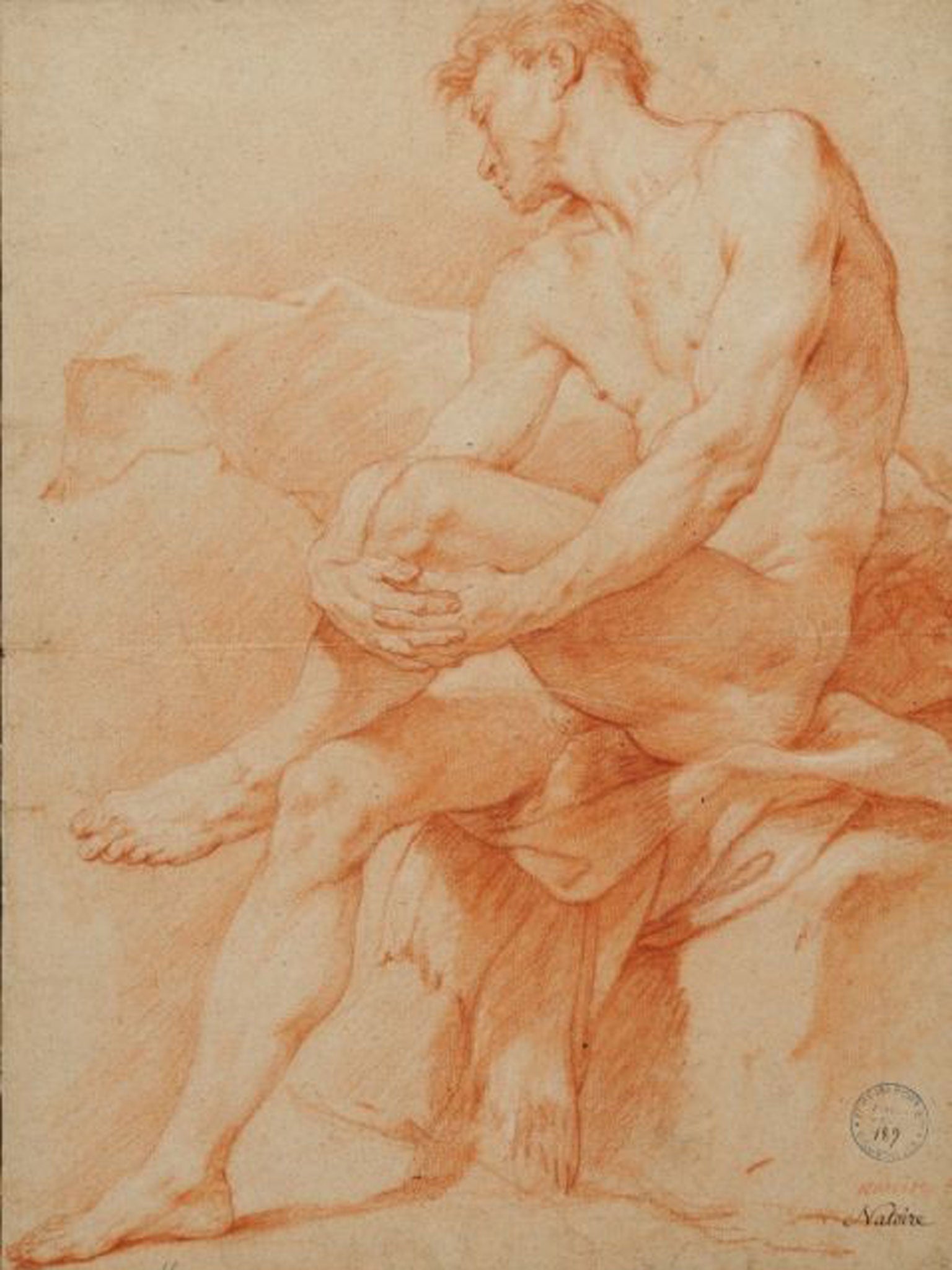

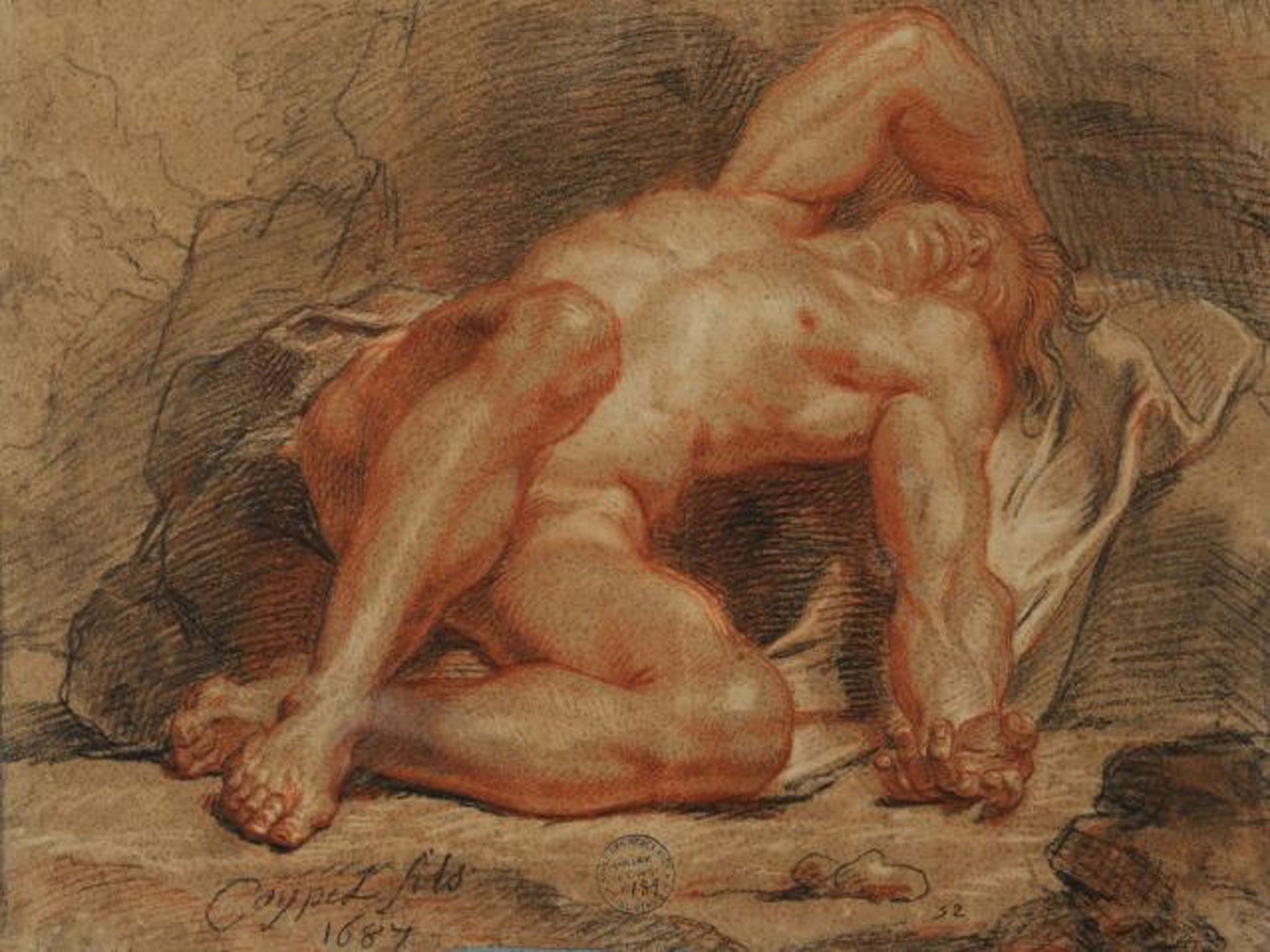

There are plenty of good names here. There’s a dramatic, unnerving picture by Antoine Coypel from 1687 of a “Man lying on his back, ankles crossed’, a virtuoso depiction of a “Titan struck by lightning”. François Boucher is represented by two relatively restrained drawings, including a dreamy “Seated man, arms crossed” and Hyacinthe Rigaud has a fine drawing, Two Wrestlers. There are the odd surprises, too. I liked Charles-Joseph Natoire’s meditative “Seated man, holding his left knee”, although he is far from being a household name.

As an illustration of the method behind French painting of the period the range of pictures is impressive. As a gallery of pictures to be viewed by the ordinary visitor, it has its limitations. After so many painstaking drawings of naked men holding exaggerated poses, one longs for a Watteau, who never studied at the Academy although he became a full member in 1717, with his fluid lines and instinctive grace.

That may be unfair. The drawings are, after all, academic exercises and called “academies”. The Wallace Collection presents them, and rightly, not so much as a collection of master drawings as a group of archived studies which can provide an artistic backbone to its fine collection of 17th and 18th-century pictures by the French academicians and court artists in the rooms above. Helpfully, the gallery provides and exhibition trail of the art, including ceramics and sculptures, which developed out of this formal training.

I’m not sure it does the cause of French art training many favours. The emphasis on life drawing certainly made the French painters and sculptors of the 18th century much more confident, and more flamboyant, in their pictures than the British, who had trouble with their dramatic renditions of classical myth. Titans were never felled by Zeus’s thunderbolt in British art with nearly as much histrionics as their French counterparts.

But the French concern with antiquity and idealised form promoted a pomposity that makes their paintings of the period verging on the ridiculous to the modern eye. Confined to the male nude in their training, most of the painters at the time portrayed the female nude in hopelessly fleshy form. Brought up drawing live models like inert sculptures, they had great difficulty in portraying their human figures as real people, preferring the abstraction of classical myth to the depiction of the human.

François Lemoyne’s Time Saving Truth from Falsehood and Envy in the Wallace Collection may exemplify the Academy virtues but it’s a truly frightful piece of pulchritudinous nonsense, however well painted. François Boucher’s The Rising of the Sun, presenting Louis XV as Triton attended by the Oceanides led by his mistress Madame de Pompadour is risible in its flattery.

It was the drawing and painting of “attitudes” and its obsession with “Antiquity” that killed so much of French art in the period, as it did its British imitators. Men striking poses tend to the ridiculous, physically as well as emotionally. Eventually the training in the classical was to produce the great flowering of neo-classical art under Napoleon with Jacques-Louis David, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres and Eugène Delacroix. So the academician approach could be said to have finally proved its worth. But in the meantime it stifled creativity.

But maybe that’s just an English view. Go to the Wallace and see for yourself. It’s an instructive show but don’t expect to get aroused by it.

The Male Nude: Eighteenth-Century Drawings from the Paris Academy, The Wallace Collection, London W1 (020 7563 9500) to 19 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments