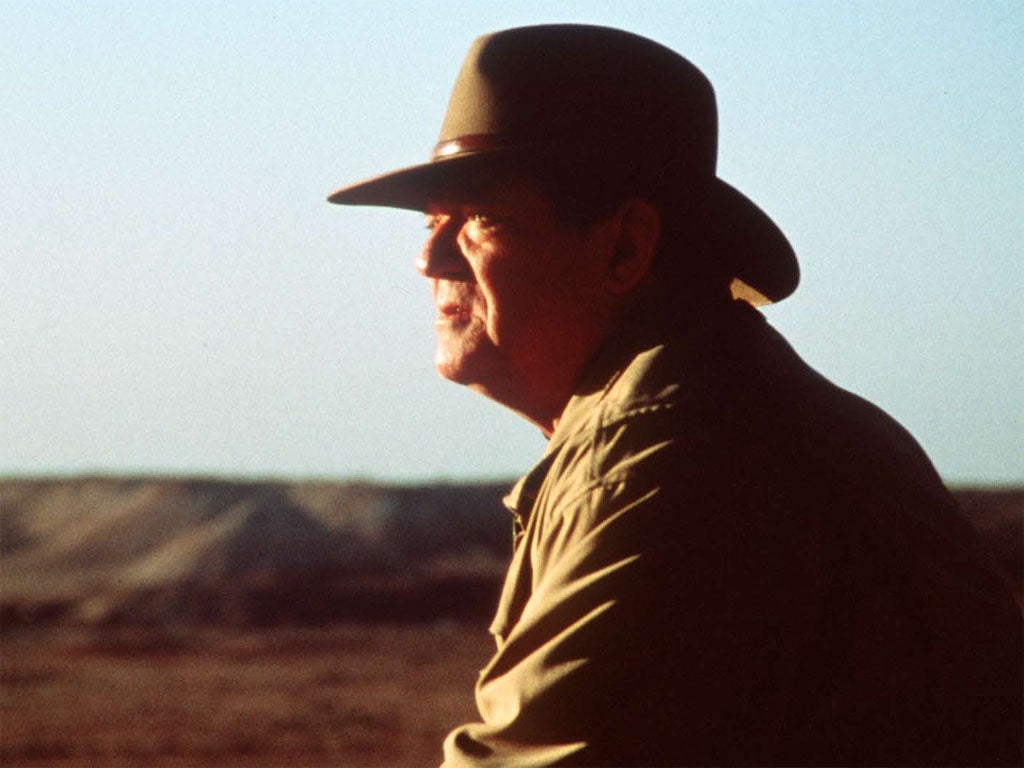

Tom Sutcliffe: The combative critic whose waspish words had more than just shock value

As with quite a lot of things these days I first read about the death of Robert Hughes on Twitter. I'd love to know what the old bruiser thought of this new medium and to hear how wittily he might encapsulate its follies. I have a suspicion that he would disapprove. But in one sense it did him proud when it came to instant commemoration.

The hive-mind swarmed, provoked by the news, and in a matter of minutes an anthology of Hughes's best lines were ticking up on the time-line – those arresting, aphoristic phrases that knocked what you thought you knew out of you and left you thinking hard about what he wanted to put in its place. Most good critics would be travestied by a 140-character limit on quotation. But tellingly, Twitter captured the essence of Hughes's clarity, memorability and pugnacity.

The aggression in the prose wasn't too everyone's taste, and his sense of combat very occasionally hampered his criticism. "A Gustave Courbet portrait of a trout has more death in it than Rubens could get in a whole crucifixion" he wrote once, which makes the point about Courbet while unnecessarily suggesting that an odd kind of heavy-weight bout has just taken place. If great art is a kind of combat it's rarely as head-to-head as that. But for any young critic reading Hughes there was something intoxicating in his reassurance that art – and writing about it – need not be an effete affair. It could involve getting into fights and winning them, not by throwing your weight about, but through the accuracy of your punches. And that art was worth fighting about was implicit in the eagerness with which he squared up.

His prose style alone was a continuous combat with the prevailing orthodoxy in art writing. Though an unapologetic elitist ("I don't think stupid or ill-read people are as good to be with as wise and fully literate ones" he once said) and a frequent scorner of the popular, he never used language that might exclude the uninitiated. Getting as many people as possible into the club was what he was interested in, just as long as they shared his interests. His The Shock of the New did more to open up modern art and its complexities to a general audience than anything broadcast before or since. The writing style was blunt, plain-speaking, briskly impatient with jargon that might conceal vacancy behind impressive polysyllables.

It's a rare ability to be able to write at the highest intellectual level with the plainest words. This paper's former critic Tom Lubbock had the gift. And Hughes did too. And accessibility like that takes nerve, since there are no opacities or obscurities to hide behind if your argument doesn't make sense. It is, unfortunately, vanishingly rare among those who currently administer and mediate contemporary art.

Look at any exhibition catalogue and 99 out of a hundred of the essays will be written not for the general public who attend, but for a priestly convocation of curators and academics. And even they aren't really expected to read them, but only to note that the right rituals have been observed, the correct authorities appeased. Certain things will be unsayable, many orthodoxies taken for granted.

It is often pharisaical, in fact, and Hughes, without getting too grandly scriptural about it, was a scourge of fine art pharisees. He hated the hype of the art market, he wrote, "because it intersects with a fatal propensity for sanctimony. I don't like the idea of art being a religion." By which he meant, I think, not that it couldn't contain the sacred, but that what is sacred can easily get lost when theologians, sectarians and dogmatists have a monopoly over access to it.

Writing directly to what anyone could see when they looked at a painting Hughes did what all really good critics should do. He fought for the priesthood of all believers.

Thin line between love and hate

It's an odd experience sitting in a theatre and thinking, "I would thoroughly recommend this but I hate it." I found it happening at the opening of the National Theatre's production of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time. It does faithful service to a book about which people feel proprietorial.

But for me it was also a compendium of theatrical pet hates. First: little model trains, tagged in someone's head as "magical". Second: actors pretending to be bits of furniture. Third, and perhaps most grating of all, slow-motion sequences. Go – I can pretty much guarantee you'll love it more than I did.

They need to stay in more

I think we can be confident that Jeanette Winterson didn't see The Trip, Rob Brydon and Steve Coogan's series about a gourmet writing expedition around the North-west. Why? Because one of the funniest sequences in the show consisted of the two of them riffing off that hoariest of all costume drama clichés, "We ride at dawn".

Why so early, they asked each other, why not get a bit of breakfast in first? They teased the phrase, tormented it and eventually left it for dead. And yet there it is in The Daylight Gate, Winterson's new novel about the Pendle witches, as if nothing had ever happened. In-joke? Or evidence that her editor doesn't watch a lot of television either?

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies