Tom Sutcliffe: The BBC doesn't need an arts strategy. It needs ambition and courage

A critical view

The BBC's Arts Editor, Will Gompertz, appears to have been in unusually candid mood a few weeks ago when he went on Radio 5 Live and described the experience of sitting on the BBC's Arts Board as “hysterical”.

“It's like being on an episode of Twenty Twelve”, he's reported as saying: “We talk about the BBC's arts strategy. And there isn't one, it transpires.” This off-the-cuff account of BBC policy-making was reported with some glee by the Daily Mail, which then went on to add up the remuneration of the executives who sit on the Arts Board, as if this was all they actually did for their salary. And you could see why the story appealed to them – all that licence-fee payers' money, chasing itself around in circles and coming up with nothing. But my own reaction, as an admirer of the BBC (and broadcaster for it), was, “if only it was true”.

I don't mean the thing about it being like Twenty Twelve. Like any big organisation the BBC has its moments of unwanted bureaucratic comedy. I meant the thing about the BBC having no arts strategy. Because there are good reasons for arguing that “strategy” might be one of its problems rather than a missing solution. This is particularly true for arts television, a field which I'd suggest is almost certainly over-managed these days, rather than under-managed. Watching Robert Hughes's The Shock of the New the other night, a landmark series granted a repeat by its presenter's death, I found myself wondering how likely it was such a series could be made now, and coming to the conclusion that the odds were a good deal longer than they were back in 1980.

This is a slightly unfair argument, of course. There's no question that BBC executives would love another Shock of the New. It's also the case that broadcasters like Robert Hughes don't come along every year – or even every decade for that matter. But it's still legitimate to ask whether a broadcaster that sets out to have a strategy for the arts, rather than a vaguer ambition about the kind of television programmes it should be producing, is better placed to deliver excellence. “Strategy” implies a pre-determined goal, performance measures, a set of tick-boxes which programmes will be expected to fill. “Ambition”, by contrast, is more open-ended, unpredictable and permissive.

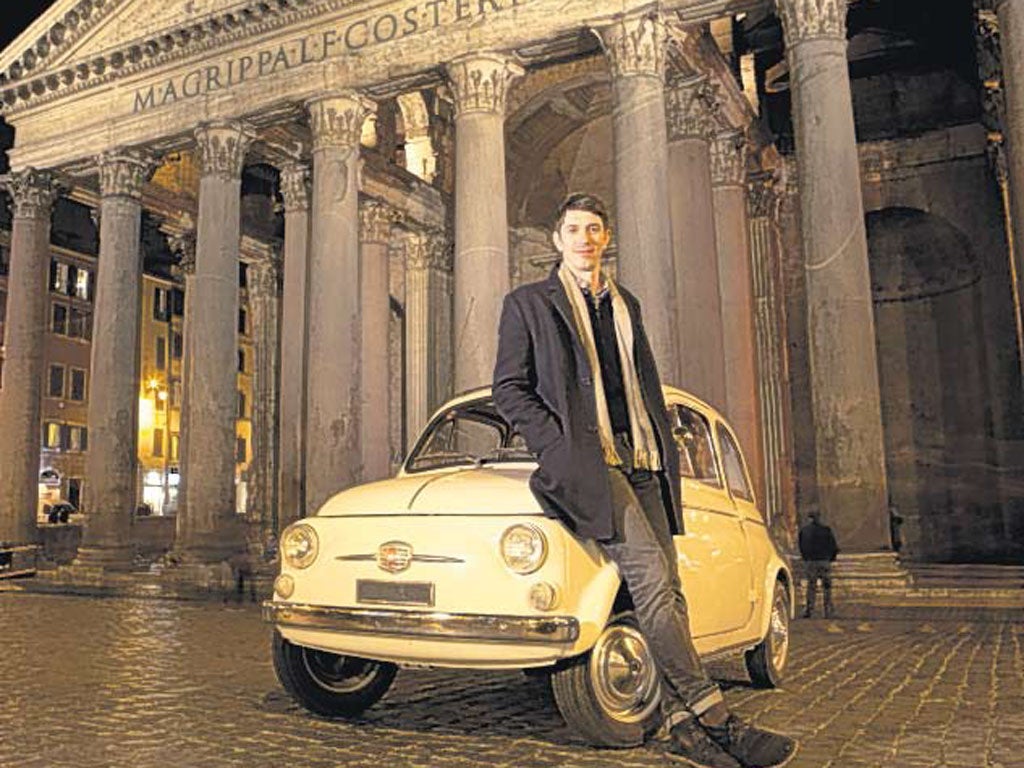

What over-management does to programmes is homogenise them – and you can see its effects all over the schedules. It's why Alistair Sooke, opening a series on Roman art earlier this week, had been required by someone at the BBC to make his fatuous opening claim that nobody thinks the Romans actually did art: the series must be presented as controversy or challenge. It's why so few arts documentaries these days have opening sequences which intrigue or tease or tantalise – because the final cut has to pass through a set of managerial sieves which are almost bound to filter out the idiosyncratic or the unexpected or the temporarily difficult. It's why we have to endure so many “journeys”, with their factitious promise of exploration and revelation.

Better, surely, to have a bit less executive supervision and a bit more creative freedom. No individual film or series should set out to fulfil a committee's notion of the BBC's artistic five-year plan. They should aim to present a passion and curiosity about their subject matter in most intelligent way possible – even if that occasionally risks leaving the lazier viewer behind. I'd happily surrender any amount of “strategy” for some revived ambition to make television programmes that could be screened again in 30 years time, and still look fresh.

Forget the photo, read the words

“It will shed new light on the poet,” a journalist writes about a photograph believed to show Emily Dickinson in her mid twenties. If it is her, it would be only the second photograph ever found, so one can understand the excitement. But looking at it, you wonder at some people's excitability. “It will change our idea of the poet,” says a spokesperson for Amherst College, going on to note her “striking presence, strength and serenity”. In fact, only if you'd believed that Dickinson remained a teenager until her death could it be described as revelatory. If you're interested in the poet stick to the poems. The picture only sheds light on the suggestibility of enthusiasts.

Too busy boasting to write

I've been intrigued by the debate over sockpuppetry, triggered by the confession of thriller-writer Stephen Leather that he used fake identities to promote his own titles, and the outing of RJ Ellory as his own biggest online fan. But one thing inadvertently revealed by the scandal is the amount of time that many writers now seem to devote to monitoring their standing in the Amazon sales list and reading online reviews. Ironically, it seems that the very thing that gave rise to the scandal – the insecurity of the writer's life – also provided the energy that eventually exposed it. When you add in the time needed to debate the matter on Twitter and write the blog rebuttals, you wonder how any of these authors have time to write the books themselves.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies