'Most important document of the last 100 years' to be displayed in UK for first time

Exclusive: Lenin's poster proclaiming the overthrow of the Russian government in November 1917 will be part of a new exhibition opening at the Tate Modern next week

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.One of the most historically important documents of the past century is going on display in the UK for the first time, The Independent can exclusively reveal.

Exactly a hundred years after the Russian Revolution set in motion events that would change Russian and world history forever, the paper that ushered in the dawn of communism will be put on show at the Tate Modern next week.

The document – a poster written by Lenin, proclaiming the overthrow of the Russian government – was one of just a few hundred which were printed by the Bolsheviks and pinned on notice boards or pasted on walls in Petrograd (Saint Petersburg) on 7 November 1917 (25 October in the old Russian calendar).

Acquired by the Tate just last year, it will be on display as part of the gallery's Red Star over Russia exhibition which opens to the public this coming Wednesday, 8 November. The show – subtitled "a Revolution in Visual Culture, 1905-1955" – will be the main UK exhibition to coincide with next week’s centenary of Russia’s October Revolution.

The historic poster, headlined “To the citizens of Russia” proclaimed that “the provisional government has been deposed”.

It told the public that “state power has passed into the hands of the organ of the Petrograd Soviet of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies – the Revolutionary Military Committee, which heads the Petrograd proletariat and the garrison” and that “the cause for which the people have fought – namely, the immediate offer of a democratic peace, the abolition of landed proprietorship, workers' control over production, and the establishment of Soviet power – has been secured". It concluded with the words ”Long live the revolution of workers, soldiers and peasants!”

A leading authority on the Russian Revolution, Professor Christopher Read of Warwick University believes that the poster is “one of the most important documents in modern world history”.

“The posters, proclaiming the October Revolution, are arguably the most important historical documents of the past 100 years,” he said.

“They symbolise the establishment of Soviet power which lasted till 1991. But they also represent the genesis of a chain of events that changed world history – and shaped much of the world we still live in today,” said Professor Read, author of two key books on the period – War and Revolution in Russia, 1914-1922: The Collapse of Tsarism and the Establishment of Soviet Power and Lenin: a Revolutionary Life.

The posters – very few of which have survived – were the very first documents issued by the new Soviet regime. The Tate’s recently-acquired example is believed to be the only one in a public collection in the UK.

It is historically important, not just because it ushered in 74 years of Soviet communism, but also because the new government it proclaimed went on to turn Russia into a highly industrialized country – and, without that industrialisation, it would almost certainly not have been capable of defeating Nazi Germany in the mid-20th century. That may well have meant that Hitler would not have lost the war, or at least not so decisively, and that Nazi Germany might even have semi-permanently conquered or subdued Russia and survived in some form post-war.

The system ushered in by the proclamation on this poster ultimately, of course, led to the spread of communism to many different parts of the world – including China, Vietnam and Cuba. The Russian Bolshevik Marxist belief in working-class political destiny (and therefore, by necessity, planned industrialisation to create a working class) was ultimately followed, to a substantial extent, by the Chinese communists – and it is that industrialise-at-any-cost policy that has ultimately allowed China to become the world’s second largest economy and one of its most powerful nations.

The results of the 1917 proclamation on the poster, due to be displayed in the Tate Modern exhibition, are still reverberating around the world.

Another historically ultra-important and extremely rare poster due to be displayed in the exhibition is one of the first two decrees issued by the Soviet Congress which was meeting in Petrograd as the revolution was unfolding.

This second poster proclaimed a decree, proposed by Lenin, bringing all land and buildings in Russia into public ownership, but ruling that it could still be farmed by families, communities or cooperatives.

It was the first proclamation of large-scale public ownership in world history.

This historic document announced the abolition of all private land ownership – and awarded all private landed estates, crown, monastic and church lands (and their livestock, implements and buildings) to local peasant communities. It also warned former private landowners, on pain of punishment, not to damage property prior to it being transferred to local community ownership and use.

The poster also proclaimed the nationalisation of mineral resources, major waterways and lakes.

The Tate acquired both documents (along with 250,000 other Soviet posters, photographs and other material) from a London-based British private collector, David King, who had started collecting in the 1970s. Mr King passed away in May last year, before full details of the history of many of the items could be ascertained.

The story of the two October Revolution items between 1917 and 2016 is therefore not currently known. However, it is conceivable that the items were bought from either Russian emigres who fled Russia for the West between 1917 and the mid-1920s – or from British or other Western left-wingers, journalists or diplomats who were in Russia at or shortly after that time. Alternatively, they may have been acquired from the revolutionaries’ descendants who had inherited October Revolution memorabilia and had decided to sell them after the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991.

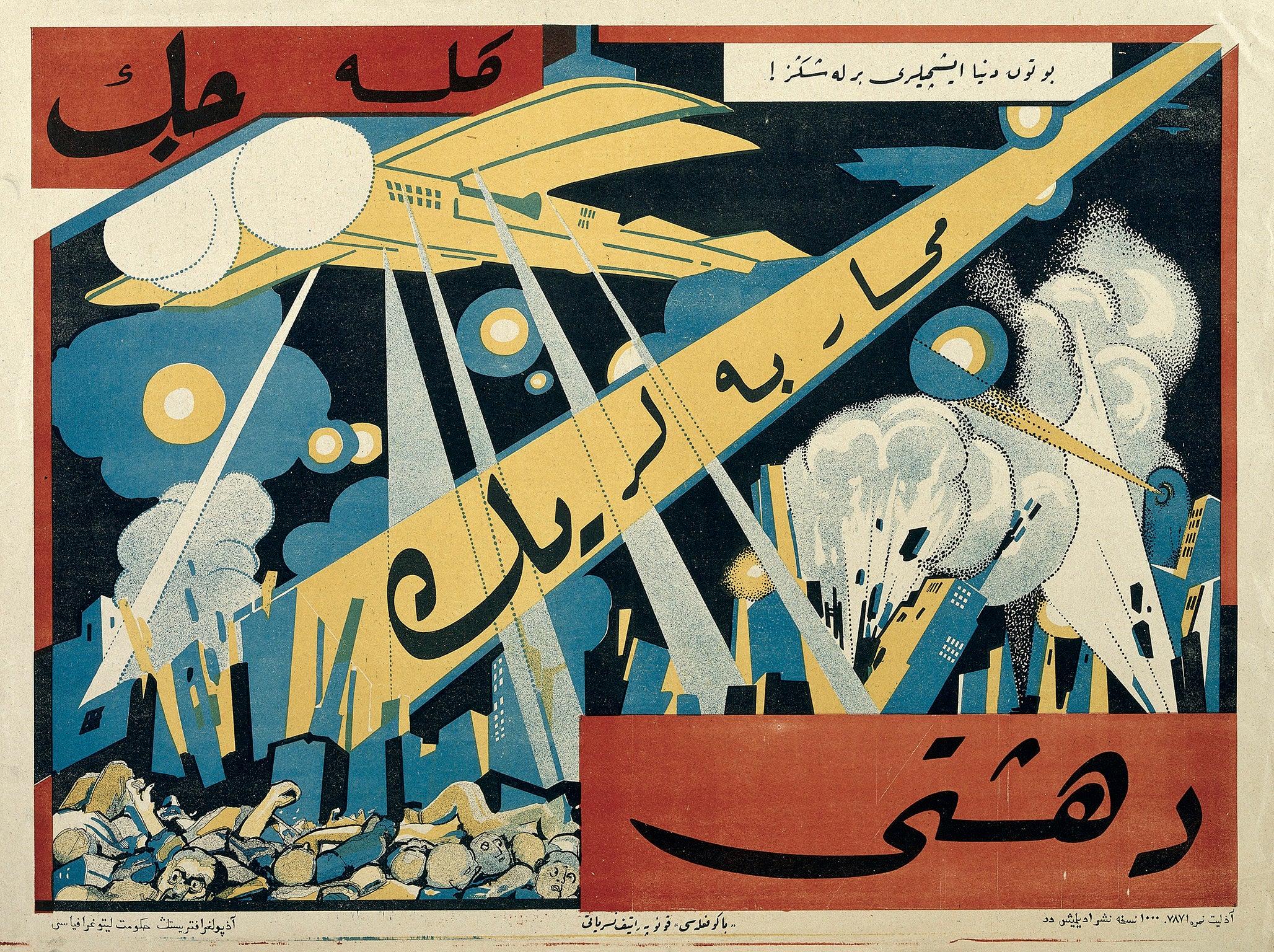

The Tate Modern exhibition – featuring some 250 items – will run from this coming Wednesday, 8 November to 18 February. Although the two October Revolution posters are without doubt historically the most important items in the show, the exhibition will also present an extraordinarily rich selection of other posters, mainly chronicling revolutionary and Soviet art from the revolution through to the 1950s. Among the artists are some who were executed by Stalin.

Also on display will be a large number of books, magazines, photographs and some paintings (representing Soviet visual culture) as well as photographs depicting aspects of Soviet history. Among those historical images are a series of police pictures of political prisoners (mainly Trotskyists, anarchists, Ukrainian nationalists and indeed Bolsheviks) many of whom were also executed during the Stalin years.

David King, who over many decades put together the vast and remarkable collection which the Tate bought last year, was the world’s leading collector of Soviet graphic design and visual culture.

He was himself a graphic designer who produced notable album covers for Jimi Hendrix and The Who. He also produced posters and graphics for the Anti-Apartheid Movement, the National Union of Journalists, the Anti-Nazi League and Rock Against Racism – and wrote several books critical of Stalin.

“He was a one-man archaeological expedition into the lost world, the destroyed world, of the original Soviet leadership,” Stephen F. Cohen, emeritus professor of Russian studies at Princeton and New York University, told the New York Times last year. “He was determined to unearth everything that Stalin had buried so deeply and so bloodily.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments