Great Works: The Hall of the Bulls (1983)

Lascaux II, Montignac, Dordogne

There are copies and copies. Some point you back to an original. Some have no original. In "The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction", the German critic Walter Benjamin observed that modern image technology had transformed art. There'd always been ways of reproducing artworks. But in the new photographic arts, every artwork is a reproduction.

He identified two extremes of image making: "with one, the stress is on cult value; with the other, on the exhibition value of the work." The typical case of the cult work is cave painting – unique, ritual images, where "what mattered was their existence, not their being on view. The elk portrayed by Stone Age man on his cave walls was an instrument of magic. He did reveal it to his fellow men, but in the main it was meant for the spirits."

The opposite case is photography and cinema. They exist to be viewed. They have no value as objects. There are no unique originals: "one can make any number of prints; to ask for the 'authentic' print makes no sense." But there is a fact that complicates this distinction. The most spectacular case of reproduction in modern times is a cave painting.

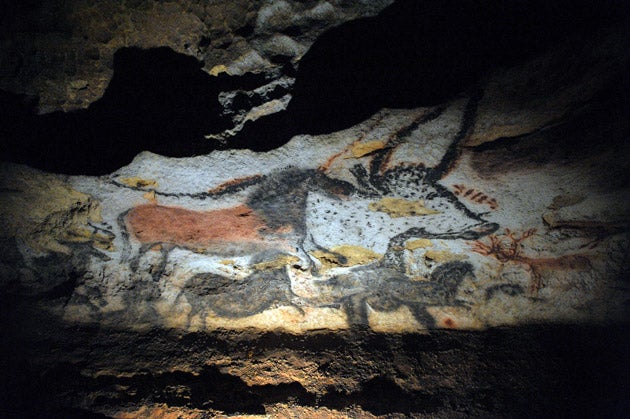

These aurochs come from the wall of the Hall of the Bulls, one of the most densely illustrated chambers in the Lascaux caves in the Dordogne. Its images can baffle the modern viewer in many ways. Were they painted for the spirits? Where did their makers get their graphic skills? Is it conceivable that these cartoony figures were funny?

They hold a more straightforward puzzle, too. This is a work with two possible dates. The first is about 17,000 BCE or older. The second is 1983. The discrepancy is easily explained. It depends on whether the images – like these bulls – come from the original caves, or from their replica, Lascaux II.

The caves, containing more than 1,500 distinct images, were discovered by three teenagers in 1940. After the war, visitors thronged in. By the mid 1950s, rot damage was becoming apparent. In 1963, they were closed to the public.

Twenty years later, an actual-size three-dimensional reproduction of the Hall of the Bulls and the Painted Gallery – two connecting chambers, holding most of the paintings – was opened underground 200 metres away. (Other Lascaux paintings are recreated at the Centre of Prehistoric Art at Thot.)

Lascaux II is not a mechanical reproduction in Benjamin's sense. Its verisimilitude is astonishing, but it isn't photographic, and it hardly could be, given that the images are integrally attached to the uneven surface formations of the caves. The simulation took 11 years, employing 20 painters and sculptors, who imitated the methods and media of the original palaeolithic artists. It is an immovable and unique copy.

On the other hand, it's clearly a work in which authenticity has given place to visibility. Lascaux II reflects a determination that the images shall be shown, in as faithful a form as possible, even if their originals can't be. And the originals, having temporarily recovered, have for some time been getting worse. Their future is now uncertain.

So Lascaux II – "Fauxscaux" – is the only way the paintings can now be accurately seen. This reproduction is destined to be not a second best, but a substitute. It's a rare case of a unique artwork being simply superseded – likely for ever – by its copy. The Hall of the Bulls hasn't been destroyed, but it has disappeared. For all visiting purposes, there is no original to see. The replica is now the thing itself.

If Benjamin was right, if the paintings were never really meant for human eyes, then things may have turned out oddly well. The magic originals have gone back to their intended invisibility, while we have a very good copy to look at.

But for some people, this is no good. The originals have a magic for us too. It doesn't directly involve spirits, but it does involve our sense that we're in touch with our distant ancestors, with their authentic handiwork and pigment and rites. Replicas won't deliver this contact. The visuals by themselves are not the point.

We need to stand among the works themselves, to be in their real presence. A copy, however exact, can never be a substitute. The closer a copy approaches the real thing, the closer it is to being a fake, a pseudo-version of the experience. There are those who would rather see nothing, than see Lascaux II.

There are others for whom Lascaux II is better than nothing – much better. It preserves the imagery and forms of the caves. It's also a wonder of fabrication in its own right. It's not only originals that hold a spell. A simulacrum is itself a form of magic.

Of course, the very finest replicas will have other problems. Without being able to compare them with the originals, you can be never sure what you're looking at. In art, the smallest details, the faintest aspect, may make all the difference. You notice something interesting in Lascaux II. Is it the work of the ancient artist or the modern copier? A reproduction by hand is inevitably an interpretation.

And it's probably only because cave paintings don't quite qualify as art that some of us are prepared to take these replicas as an acceptable substitute. Suppose the Lascaux paintings could be credited to an artist, with a known name and style and biography. We'd be more likely to see Lascaux II as a kind of forged signature.

If Leonardo's The Last Supper finally disintegrates (as it's been threatening to do ever since it was painted), it's unlikely that it would be recreated as The Last Supper II in a specially constructed hall nearby, for the sake of visitors to Milan. Leonardo's handiwork is nearly lost, through decomposition and restoration. There are many imitations of his famous picture around the world. But none of them is presented as a substitute experience.

Why not, though? For there is another lesson in Lascaux II – a practical lesson that could be followed more widely. Replicas are useful. Even when originals can still be seen, they often can't be moved. And even when copies aren't perfect, they're often good enough. Unlike writings and music and photos, most visual artworks still suffer an unfortunate limitation. They can only be in one place at one time. So don't be superstitious about authenticity. Never mind about spirits, or ancestors, or artists. Reproduction for the sake of distribution: that's the cry of the caves.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies