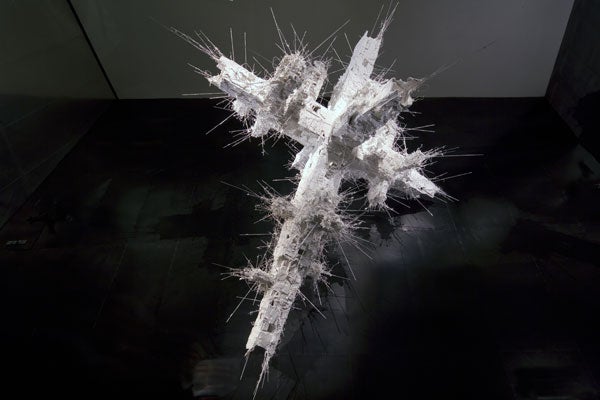

Great Works: The Crusader 2010 (5.4 x 3.8metres), Gerry Judah

Imperial War Museum North, Manchester

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Over the next 12 months you will be able to see this sculpture as you enter the main exhibition area of the Imperial War Museum North, at Salford Quays in Manchester. It is high-hanging dramatically from the wall, bulky, cross-shaped, slightly askew, radiantly white against the black-painted, stainless-steel panelling, as if it might be the suffering saviour himself slumped slightly forward and sideways in his death agonies. This Libeskind building, with its soaring, leaning, steel-plated walls, its eerie unpredictabilities, is an agglomeration of odd, tilting angles, and so it comes as no surprise that this huge, depending sculpture is not smartly squared up either.

It is a museum that looks at war from the point of view of particular human beings. Many of the objects that you see in it belonged to people whose names we know – that is its particular poignancy – a mess kit, identification papers, photographs, rows of helmets. This is not one of those. This sculpture by Gerry Judah is a generalised symbol of the human suffering caused by the enduring madness of war.

The Crusader is dramatically posed, lighter-looking than its mass and its bulk seem to suggest, directly opposite a Harrier Jet AV-8A, which is nosing down as it comes into land. Like Judah's sculpture, the Harrier too is tilted to the side as it simulates landing – they seem to be in a kind of stately come-dancing partnership, one pulling decorously away from the other, and you catch sight of the sculpture through the underside of one of the Harrier's 25ft wings, radiating the kind of white light that you might expect of a religious symbol of some kind. Is this a religious symbol, then? The jury is still out on that one.

What cannot be denied is that it is altogether a curious thing in its polyvalency. You can read it in so many different ways. There is the blatant Christian symbolism of the cross shape itself of course, but once up close, staring up at it, you recognise that this is in fact a representation of a fragment of blasted urban landscape built up and away from that cross shape, which consists of a couple of intersecting streets, containing tower blocks, water towers, and a great, spiky, bristly intermeshing of aerials and satellite dishes, all messily interwoven, the tattered remnants of a neighbourhood pulverised by bombs.

Yes, the sculpture is a kind of cross-shaped island, hanging in the air, on its side, and we are privileged to be getting an almost vertigo-inducing aerial view of it. Yes, it is as if we are looking straight down on it – we can see into the hollowed out shells of buildings, the shattered fragments of collapsed staircases – except that we are, in fact, looking up at it from the floor. This means that we are seeing it from the perspective of the man who might have flown over it and done all the damage, and that uncomfortable thought brings us up short. Yes, perhaps we we are the ones who have committed all these the atrocities in the first place.

There is another interesting fact, too. The almost virginal whiteness strikes us as odd. This is a scene of devastation, and yet it is also strangely etherealised, rendered unreal, by the fact that, tonally speaking, there is nothing here but a dazzling, disembodied whiteness so suggestive of purity and otherworldliness. That word disembodied leads on to another thought. There are no people here either. Not a fragment or a trace of a charred body, not a smear of blood to be seen anywhere. Why is this hanging fragment of urban landscape, which seems to have been smashed by some enraged fist, so empty of any human presence? The sculpture feels utterly still, floating here, wrapped in its own witnessing silence, as if it is in some way a posthumous testimony of some kind. It feels like a shroud-like witness to what happened long ago, the afterlife of a long vanished civilisation of bloodthirsty barbarians, so touchingly unblemished now, and with all evidence of human pain bleached out. A second Pompeii perhaps, magically projected forward into the world of the here and now.

As we look more and more, the general shape seems to change and then change again. Its tilt – that pronounced list – seems to suggest a mighty ship roiling in the waves; looked at again, and it seems to be spinning through the air, slowly turning as it goes. Yes, there is an overall lightness about it, hanging here, as it does, so patiently, in this dazzling, transfiguring white light. And especially so when we see its ghostly form, almost its visual after-echo, reflected in the unpainted stainless steel panelling of the wall close to which it hangs.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

Gerry Judah was born in 1951 in Calcutta and grew up in West Bengal. His family moved to London when he was 10 years old. His sculptures explore the devastations of war and the effects that recent conflicts in Eastern Europe and the Middle East have had on the environment.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments