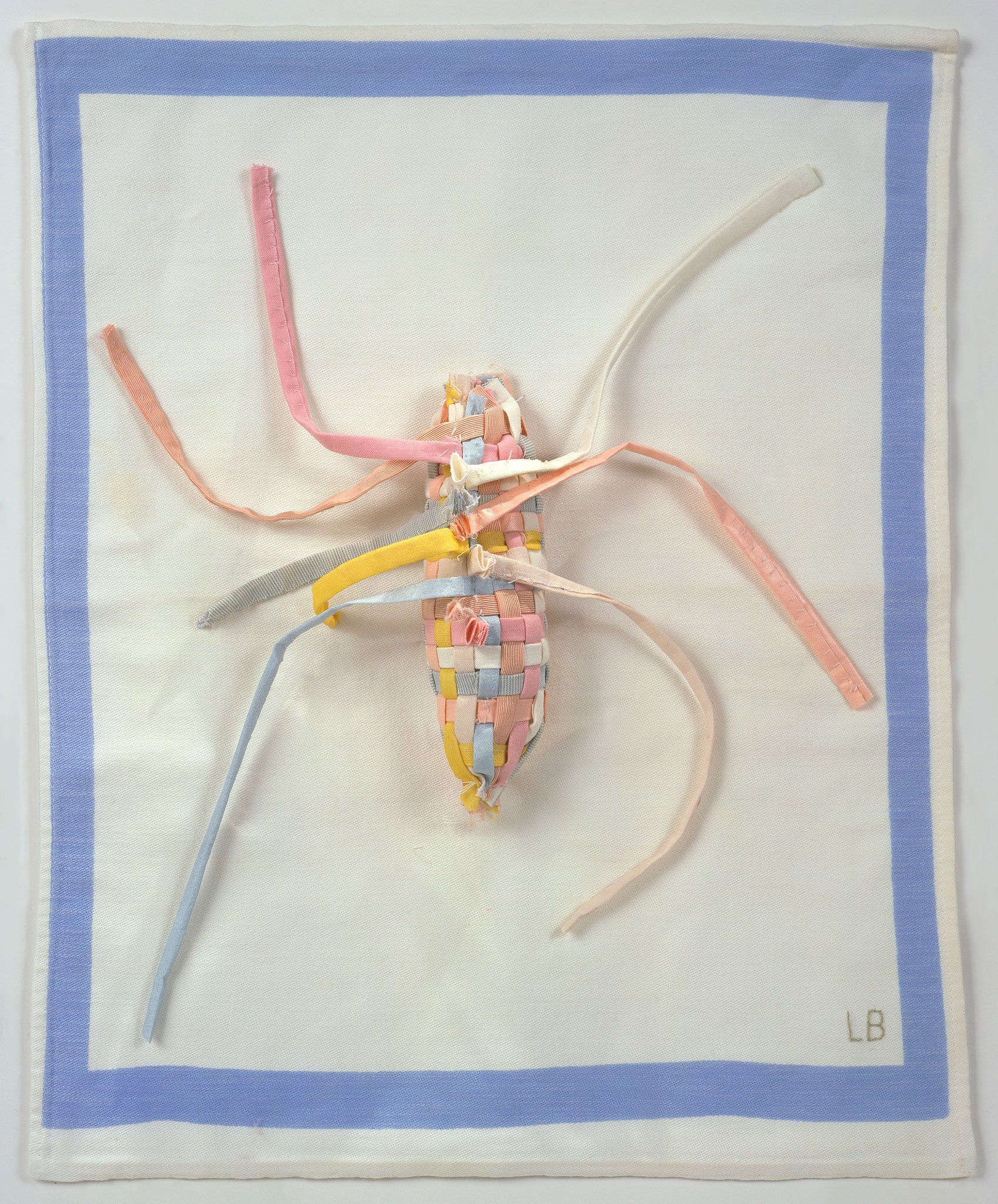

Great Works: Spider (2007) by Louise Bourgeois

Private collection

The closing lines of Robert Lowell's great poem, "Mr Edwards and the Spider", even as it probes and tilts at the primitive, hell-fire puritanism of a bygone New England, also seems to summarise a common attitude towards the spider itself: '...but the blaze /Is infinite, eternal: this is death,/ To die and know it. This is the Black Widow, death.'

Yes, to many a nervy, fearful soul, the spider is the stuff of nightmare. It lives to entrap the unwary. Christianity commonly saw in the spider a symbol of the devil, who lives in order to deceive. Minerva turned Arachne, that much accomplished seamstress, into a spider as a punishment because she was better at the art of weaving than Minerva herself, who was the protectress of that trade (and many others), a kind of guild mistress of the mythological world. All the odder then that Louise Bourgeois, who spent more than 60 years of her extraordinarily long life, making spider images – the first was in 1947, and it looks boisterously, almost harmlessly cartoonish – generally spoke of the spider other than in terms of entrapment.

To Bourgeois, the spider was often the symbol of the motherly protectress. What is more, the web the spider wove could just as easily be regarded as an object of great beauty and elegance – a recent show of Bourgeois' fabric works put on display many pieces of embroidery that were variants upon the delicate, wave-like out-fanning of the spider's web.

What the artist may be presenting here is a spider as a force for good – quite the opposite of the traditional Christian view we referred to above. What is more, the spider – as Robert the Bruce discovered – is a resourceful creature, a creature that has the capacity to show us the way. When a web is destroyed by a careless or a malevolent hand, the spider does not attack its foe. It works patiently away at repairing the damage.

There are further reasons why Bourgeois' spider might be regarded as a relatively benign creature. Autobiography undoubtedly played its part. Her mother was a restorer of Aubusson tapestries, and Louise herself assisted in that workshop as a child, repairing a missing foot here, a leg there. So weaving, for the Bourgeois family in general, and for this child in particular, was a healing, restorative activity. Far from destroying or entrapping, it returned the damaged object to a condition of beauty.

The spider stuck to the side of this page, a small, delicately plumped fabric work with a gorgeous trailing of polychromatic legs, could not be more visually alluring. Each of its sprawly legs is of a different colour, as if tricked out for some cabaret performance. Those feelers slither their way out towards that circumscribing boundary wall of thickish sky-blueness, which is a lovely tonal match with all the rest. It is also quite small, like a snug-shaped, nosy-ended cartridge. All this is fairly unusual.

Many of Bourgeois' spiders were not small at all. In fact, they were huge, and in spite of much of what I have said about Bourgeois' positive attitudes towards this creature, they look menacing, terrifying. Their staging in exhibitions often plays into their Hitchcockian qualities – they hang on a wall, half in shadow. They loom over us. They may be emblems of the arachnid as our supreme protectress – but, more to the point, they are also there to repel by the sheer horror of their looming, predatory-looking presence. Not so this one, though. This is no Black Widow called Death. This is reassuringly lovely. Unless, of course, all this colour, all this under-and-over stitch-work, is a lulling tease of make-believe.

About the artist: Louise Bourgeois

Born in Paris in 1911, Louise Bourgeois did not receive great acclaim for her work until her seventh decade. Much of her work is obsessive, inward, improvisatory, rooted in Dada, Surrealism and a kind of savage feminism. Many of her later works consist of entire enclosed environments in which solitary beds, chairs and bottles stare across at each other balefully through a gloom of entrapment. She died in 2010.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies