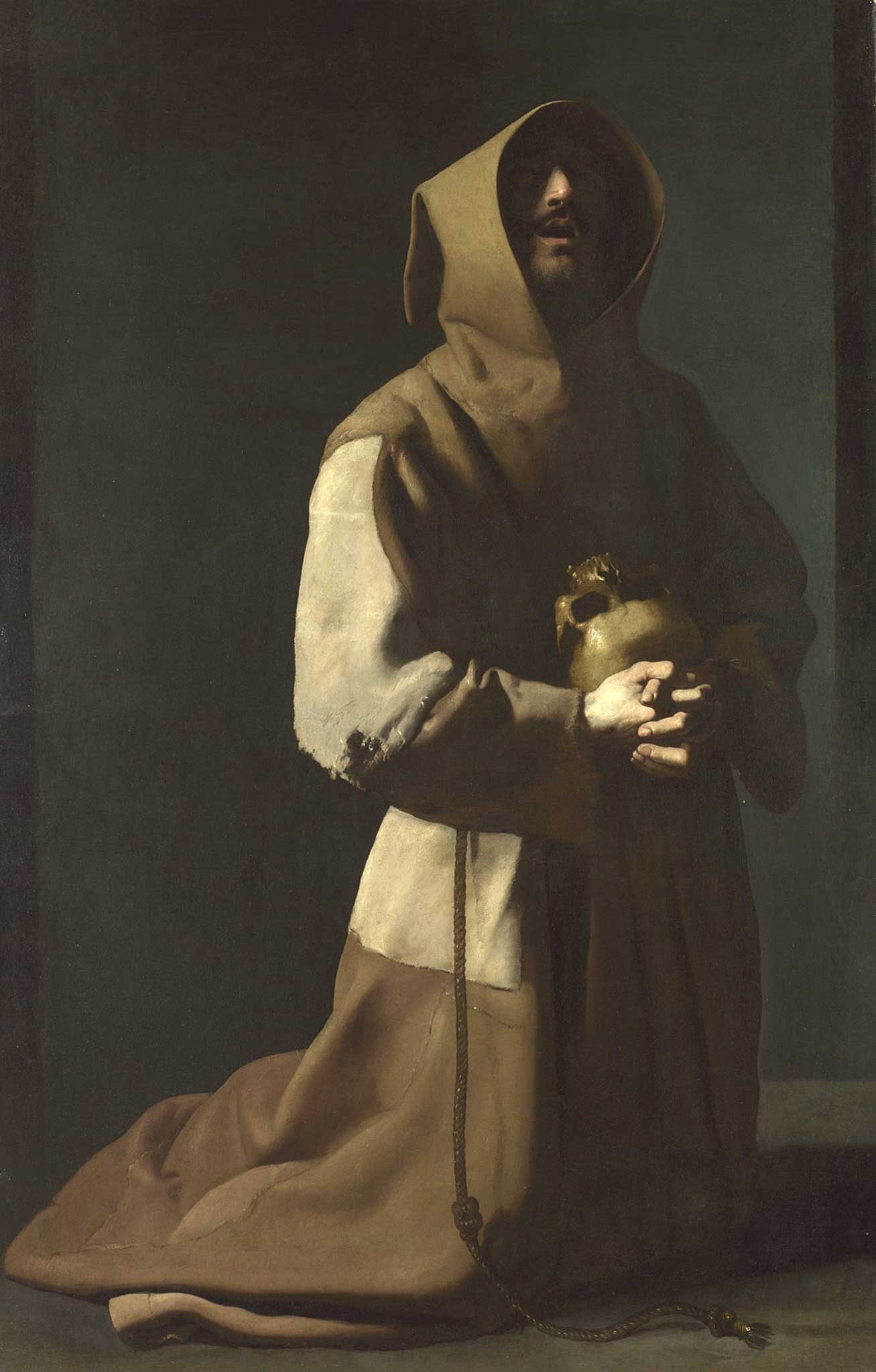

Great Works: Saint Francis in Meditation (1635-9) by Francisco de Zurburán

National Gallery, London

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There is much toing and froing in the 30th room of the National Gallery. Then, all of a sudden, you come upon this, by a youngish painter from Seville, quite different in atmosphere from its neighbours. It feels drawn in, close pent, and it bears down upon you, from a height. Yes, you have to tilt your head to look up into the opened mouth of the praying, kneeling St Francis.

The figure itself is huge, monumentally so, though it does not quite seem so at first glance because the saint is kneeling, sawn off at the knees you might say. My goodness, what a towering and haunting presence he would be, standing, with that pointed, Capuchin hood of his!

It is a solitary drama, an inward, prayerful wrestling, and the sense of much of what is happening here is bodied forth by the engulfing shadow, cut into by that dramatic shaft of light pouring in from the left, picking out the nose and, less distinctly, the beard, the moustache. There is almost nothing beyond the man himself, and there is often nothing other than these solitary presences, suspended in blackness, in Zurbarán's paintings. Note this habit he is wearing, and how threadbare it is. It is a patchwork of pieces, that is why it varies so in colour from brown to very light brown. See how wounded and out of sorts is the material at the elbow.

Interestingly, this threadbareness of the fabric of the habit rhymes very well with the condition of the frame of the painting, which is not in such a good state at all – you could begin to count the worm holes if you should so choose. What age is he, this saint? Quite young, it seems, though we cannot quite be sure. That is the intention, evidently, to make us unsure of almost everything but that mouth which hangs open, prayerfully, supplicating, endlessly, soundlessly muttering, as the saint clutches, at the height of his waist, a skull that is itself tilted up as if in interrogation.

The fact that the skull is upside down makes it quite difficult to read it as a skull – it could be a double-handled ceramic pitcher, you half-think, until you have scrutinised it a little more closely. And when that happens, you experience a slight frisson of alarm. These are the eye sockets of a dead man that are staring directly into the eyes of the saint, and reminding him perhaps that the single most important matter upon which he needs to be concentrating is that sudden great leap from life to death. Everything between is the transient folly of the world.

About the artist: Francisco de Zurburán (1598-1664)

Unlike his younger contemporary Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, Franciso de Zurburán was a painter of the darkness of the human soul. Silent presences wrestle in near empty, yawning spaces. Later in life, the fashion for Zurburán's grave depictions of spiritual passion passed away, to be replaced by a taste for Murillo, so saccharine, sweet and lightsomely cheerful by comparison.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments