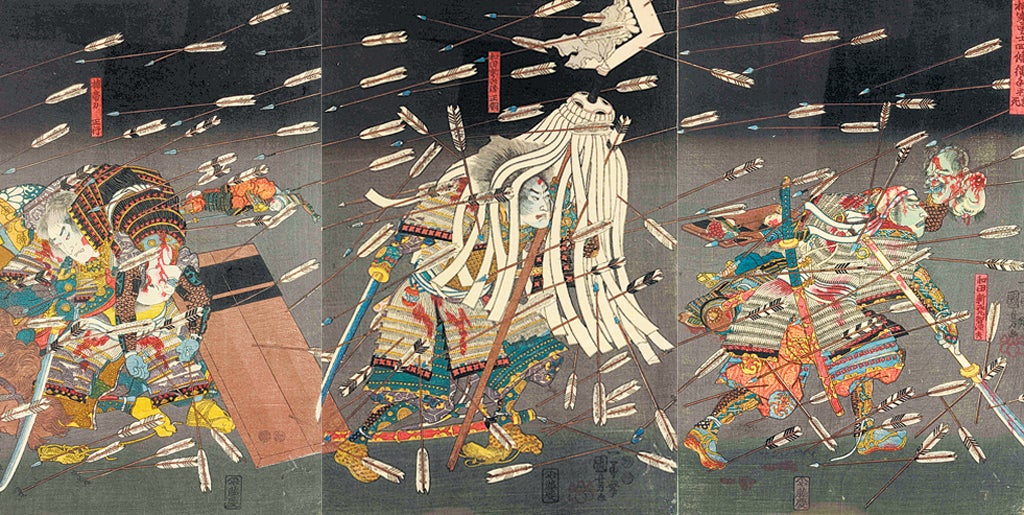

Great Works: Last Stand of the Kusunoki Heroes at Shijo-Nawate 1851 (left to right: 38cm x 26.2 cm; 38.2cm x 25.7cm; 38 cm x 25.8 cm) by Utagawa Kuniyoshi

British Museum, London

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Great art can often seem quite cloistered, set apart in its cultural loftiness, the stuff of museologists and finicky, Harris-Tweeded connoisseurs. These feelings are often underpinned by the grave monumentality of so many of the wonderful buildings in which much of this art is displayed. We all know it so well, don't we? It helps us to walk tall among those who know just a little less, hem hem.

Not so this triptych of three Japanese woodblock prints from the middle of the 19th century though. What shocks us at first is its vivid feeling of nowness and contemporaneity. It feels hectic, noisy, pullulating with heady violence. Its essential visual rhythms enthral us: that back-and-forth pushing of the three warriors as they fight back against what seem to be near-impossible odds. See how the arrows of the unseen enemies teem leftward in great, swooping, clattering droves as the three pale-faced-almost-unto-death warriors – stare into the ghastly blue pallor of their mask-like faces – push rightward in an ever-more desperate effort to gain ground... Their burdens seem near impossible. The warrior in the vanguard of the three, Wada Shinbei Masatomo, is carrying a couple of decapitated heads – the one we can see so clearly is grinning even in death – swinging them out in front of him in a gesture of defiance. Their leader, Kusunoki Masatsura, the last of the three, pausing momentarily to lean against the corpse of a horse, is labouring under the weight of a dead body sprawled across his back, which may be that of his fallen younger brother. That corpse helps to shield him from the mighty, unstoppable spray of arrows. The central figure is driving forward beneath the inadequate protection of a woefully collapsing battle standard. Only the leader for the day forges ahead, eyes in a kind of trance-like engagement with those of the enemy, as he shakes those heads like a brandished fist. This vivid evocation of a medieval battle – which can be dated very precisely to the year 1348 – almost smacks you in the face. Its cluttered liveliness, its pell-mell fury, its violently raucous disorder, is exhilarating to scrutinise in all its gorgeous decorative intricacy.

Can it really be the year 1851 when this print was made? There is a shocking immediacy about it. We feel that it belongs as much to our culture as to theirs, to these times as to those. We have been plunged into a world of superheroes of the present tricked out in the gorgeous apparel of times past – the warring samurai of ancient Japan. Can that be said of any image painted in England in that year? Here is just one taster of that year. Think back to what was made by William Holman Hunt in 1851: The Light of the World, in which a maudlin Victorian Jesus knocks on the door, lantern in hand, pious gaze looking beseechingly back at us, waiting to be admitted. Hunt's painting draws us back into a world of near-ossified religiosity which seems so culturally remote from us.

Not so Kuniyoshi, for all that he lived more than half a world away. Why does this image seem so vividly alive in the present though? In part, this is not too difficult to explain. The works of the enormously popular printmaker Kuniyoshi – and they had run into thousands of images by the year of his death – fed into manga comics and much else. You could say that so much of what he made formed a part of the great legacy of what developed, closer to our times, into popular cartooning. Such images as these have dispersed – like these shooting arrows – throughout popular culture. They are in the air everywhere. They have also dispersed into such worlds as video-gaming. Even now such a battle scene as this one may be unfolding in your basement. Having said that, popular cartoonists seldom bless us with such fineness of detail. For all that, there is the same spirit of brash and colourful adventure, and the same ferociously simple message: kill or be killed.

Why was Kuniyoshi making such images at this time? This is one of many images he created of valiant battles against terrible odds, fought against human beings of other clans, giant carp or grisly spectres. Japan itself – as a country, as a nation, as a preciously bejewelled fragment of cultural identity – was under threat as never before. Its centuries of proud isolation had been breached. Enemies – from Europe and elsewhere – were circling, battering at the gates. This image, you might say, was one of many popular attempts to reassert a proud identity which was currently under threat.

This is the majestic few – the three musketeers, you might say – against the unseen hordes from without. What better way of stiffening the backbone of resolve than to remind his fellow Japanese of their great warrior heritage, to re-establish historic continuities?

And here at last we do find a link with England. Not long after the first Great Reform Act significantly – though not hugely significantly, it has to be said – widened the franchise, the English Parliament building, which had been largely destroyed by fire in 1834, began to be recreated in the Victorian Gothic style. The young Victoria, who ascended the throne in 1837, grew to maturity at the same historical moment as the emergence of a new-old image of England's greatness, and the building was soon to come under the symbolic protection of a sculpture of Richard the Lionheart, sword raised, just outside that Parliament's walls, quite as ferocious, defiant and triumphantly backward-looking as any samurai warrior.

About the artist: Utagawa Kuniyoshi (1797-1861)

Utagawa Kuniyoshi was born in the city of Edo (now Tokyo). He was hugely prolific as a printmaker, and his work encompassed an enormous range of moods and manners. He could evoke the pathos of a dying samurai warror, the seductive beauty of a courtesan or the impish humour of a wild animal. His work is astonishingly zestful, and it appears to anticipate so much of the popular art of the 20th century.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments