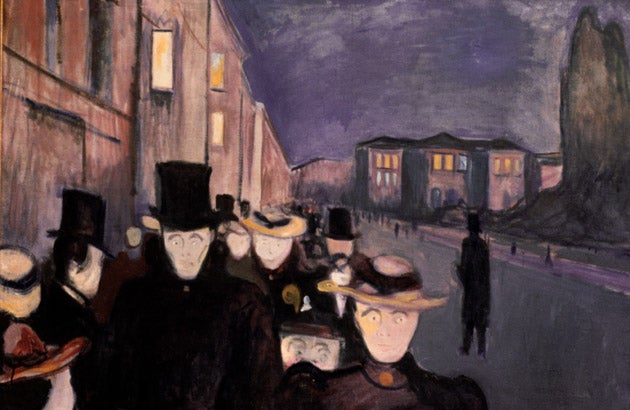

Great Works: Evening on Karl Johan (1892), Edvard Munch

Bergen Art Museum, Norway

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A few decades ago a strange message used to appear in British newspapers. Though now it might look like interference in our national affairs, in the 1970s the Democratic People's Republic of North Korea used to buy half- page advertisements in the broadsheets. They carried a statement from its then leader, Kim II-sung.

At great length, in dense print, he explained the superiorities of the communist system. These were not only material. In our private lives too, Kim said, deprived of socialist solidarity, we in the capitalist West were afflicted by "the tragedy of isolation". It was an oddly effective form of appeal. He seemed to know our hearts. It was not only the hungry for whom communism held an answer, but the lonely too.

What's more, Kim's message had surprise value. Never mind Korea and communism: we in the West simply don't expect to find existential concerns aired in a political context. The tragedy of isolation? In a poem, a song, a film, a book of philosophy, maybe – but not in a party manifesto, a leading article, an editorial cartoon, a parliamentary speech, a propaganda poster. We make a firm distinction between public and private issues.

There was one brief exception to this rule. The slogans of May 1968 fused political and personal liberation. Boredom is counter-revolutionary! they cried. Live without dead time! Under the paving stones, the beach! On the Paris barricades, alienation and repression were live questions. Since then, normality has prevailed.

It makes sense to campaign against drugs, knives, taxation, poverty, corruption. But there are no votes in a debate on alienation, anomie or angst. You don't find one party declaring war on solitude. You don't find another offering a package of measures to contain the danger of the crowd-mind. The human condition is off the agenda.

Existential issues have, of course, been treated eloquently in modern literature. The crowd and its discontents often come up. Think of Eliot's commuters in "The Waste Land": "Unreal City / Under the brown fog of a winter dawn, / A crowd flowed over London Bridge, so many, / I had not thought death had undone so many."

Or there's Jean-Paul Sartre's vision of the Métro crowd, where every individual becomes a collective, anonymous They. "To go from the Métro station of Trocadéro to Sèvres-Babylon, They change at La Motte-Piquet. This change is foreseen, indicated on maps etc. If I change lines at La Motte-Piquet I am the They who change... I insert myself into the great human stream, which from the time the Métro first existed has flowed incessantly into the tunnels of the station La Motte-Piquet-Grenelle."

Such words could be put on banners. They aren't. These troubles are none of our politics' business. Sometimes, though, an intrusion comes from elsewhere. There are works of art that push the existential into the public realm.

Edvard Munch was never happy. He objected every way. He saw singledom as misery. He saw coupledom as bondage. He saw rooms as claustrophobia. He didn't care for street life either. Evening on Karl Johan takes place on the main street in Kristiana (now Oslo). It shows a zombie-passeggiata.

Gas-lit, moon-faced, gazing ahead, moving as if under hypnosis, a crowd that might have flowed out of Eliot or Sartre presses straight towards us. Geometry makes it inexorable. The descending diagonal of the receding houses continues into the slanting edge of the advancing crowd. It impels the people along, and binds them together into a collective force. But each face stares out in our direction, saucer-eyed and separately. This is a mass of solitaries.

What is it makes Munch uneasy in crowds? Perhaps he wants to join in and finds he can't. Being in gatherings only makes him painfully aware he can never escape his solitude. Perhaps (more likely) he wants to be alone, and fears the way crowds threaten his isolation. The dark lean figure, in the middle of the road, walking apart and away, is likely Munch himself.

Whichever, it sounds like a private anguish. But Evening on Karl Johan isn't a private image. Its visual rhetoric is thoroughly public. It has the power and directness of propaganda. Large simple shapes, bold tonal contrasts, explicit imagery: this picture could speak to us from a hundred yards away. You could blow it up and paste it up on the very street that it depicts. It announces "The Anxiety of Crowds" as boldly as any Soviet poster ever announced "The Dictatorship of the Proletariat".

Munch's painting makes angst into a public cause. He probably takes the other side to Kim's. The tragedy of isolation? Quite the opposite. Resist the smothering social. Stand up for solitude. Get out and vote for the party of the alone.

About the artist

Edvard Munch (1863-1944) lived for a surprisingly long time, far into the 20th century. But his famous images are all young man's works. They were done in Germany within a single decade around 1900. You hardly need to know more of his life at this time. All the biographical yield is on the surface of these pictures. Fatal attraction, the impossibility of love, the agony of being: everything is perfectly clear. Yet Munch is an artist with a twist. The message is misery, but the effect is cheering. There's nothing like 'The Scream' to put a smile on people's faces. Its extreme emotional torment makes us feel by contrast nicely normal. Still, the works do seem to portend an early death or debilitating insanity for the artist, and having had almost all his good ideas, Munch had his promised breakdown – but he recovered, returned to Norway, and worked on, making generally more serene pictures.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments