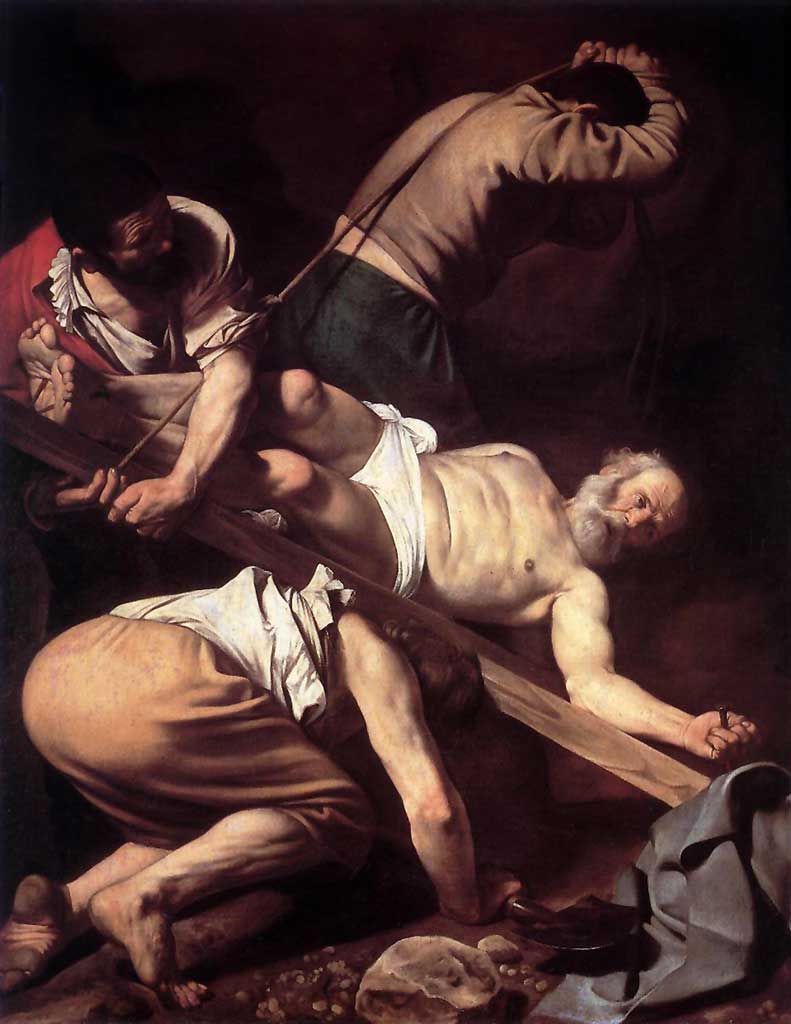

Great Works: Crucifixion of St Peter, 1601 (230cm x 175cm), Caravaggio

Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Caravaggio had been painting large altarpieces for only two years when he was commissioned to make this one for a church in Rome. The acquaintance of a cardinal had made it possible. Ah, large-scale ecclesiastical patronage. The stuff of any young painter's dreams. And what a shock it is! No wonder that the parishioners hated it so much when it was finally unveiled – and they really did hate it. Its sense of rude urgency is quite extraordinary. You can tell at a glance that it was not worked up from a series of painstaking preparatory drawings. That was the more customary way. That was what Rubens, for example, would have done.

No, this is a quite arresting depiction of life dragged in from the street. This is a quartet of ordinary men, day labourers, street loungers, bar proppers, pressed into service in exchange for a sweaty palmful of scudi, hustled into a studio brightly lit with torches, by some painter with a slightly manic, homo-erotic gleam in his eye.

Yes, what we have here is surely not a painting at all but something more akin to the urgency and instantaneity of a photograph. Is that not right? Although this work was done in 1601, and although it still hangs in the church of Santa Maria del Popolo in Rome, it surely should be attributed to an epoch in which photography, and all it could capture of the moment, was beginning to seize the initiative from painting. What we have here is a graphic, snatched instant of the crucifixion of an old man. There is no dignity here, no serenity, no pity. And certainly not much religion to speak of – despite its subject being the crucifixion of St Peter, the man who insisted upon being crucified head down, the other way up from his Lord and Master.

This is a snapshot of some no-one-in-particular being caught by the undignified speed and the incontrovertible truth of the painter's cameraphiliac's eye. What is its real subject then? Human sweat and toil. There is bustle and labour and heaving and pulling and groaning. The slightly dazed, bewildered, bearded old saint in the loincloth looks around and up, a little taken aback at the sight of the heavy, brutish nail that has been driven through his clenched left palm. What in the name of God is it doing there? What kind of terrible dream is this that he hopes to awake from in paradise?

Meanwhile, the rest of the savage crew of labouring men simply do not care, do they? It is simply not what they are concerned about. There is a job in hand here, to hoist an old man up on a couple of crossed planks as quickly as possible – yes, who knows what the hourly rate might have been for this sort of hard, bodily toil in those days, and how many others there were standing or lying nearby, being threatened and taunted by Roman soldiery as they waited for similar treatment?

What is so marvellous about the seizing of this moment of pell mell activity is how utterly convincing it is. It is as if we have been struck on the jaw. Everyone is on the go. All the characters here are pulling or twisting or turning or weight-bearing. Everyone is moving in a slightly different direction. That helps to energise the entire work. Peter, who is pretty solidly muscular for an antique saint, is writhing sideways to get a better look at his humiliation. The man with the rope is heaving it up his back, straining to get the cross upright. It is as if the painting is enacting the crude business of pulling itself apart. It is all so sudden and awkward within the fairly tight compositional space of the painting.

We immediately recognise how shocking this version is, though, and why it would have offended so many. This is a painting, commissioned by the Church, about the crucifixion of the man who had been anointed by Jesus himself to be that Church's rock, but it is utterly drained of the kind of spiritual resonance we might expect from any treatment of this subject matter. Caravaggio is determined to snap men as mechanisms, men as heaving and sweating job-doers. Look at the filthy soles of the feet of the man whose buttocks are presenting themselves to us so fully and so roundedly. The local parishioners took particular exception to those feet. Had prideful buttocks ever played such a dominant role before in a religious painting? That young man is nothing but an abject fulcrum for those two planks, he is the means by which it will be hoisted up into the air. Has he been working already? Perhaps. His right hand is still closed over the end of his spade. Perhaps he has been digging the hole for the bottom of the shaft of the cross to be plunged into. It is all so sweaty, so punishingly abject.

But it is also something quite other than all these things. This is a glamorous painting of these men. The dramatic lighting helps to lend it that glamour. The washings of light across skin and cloth have helped to give these bodies a real, toned shapeliness, a kind of theatrical panache. We admire their beauty. Caravaggio did too, no doubt.

ABOUT THE ARTIST

The life of Michelangelo Merisi (1571-1610), better known as Caravaggio, was relatively short – and brutal. He brought naturalism to new heights by painting directly from the model, and he injected into the art of painting an extraordinary sense of drama – due, in part, to his revolutionary way of lighting his paintings. Some of his earliest paintings were gorgeous still-lifes. By the middle of the 1590s he was working in Rome, and beginning to paint religious paintings on a large scale, some of which were regarded as vulgar and sacrilegious. He fled from Rome after killing a companion in a brawl. He died of a fever, aged 38, while on his way from Naples to Rome to receive a pardon.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments