Tom Lubbock: Gormley’s One and Other will turn out to be many things

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The logo for the project suggests something stark and minimal. In silhouette you see the concept in all its purity. It shows the empty plinth and somebody standing on it - youngish, male-ish, but nobody in particular. Here’s an average, anonymous human, set on a pedestal. In other words, it looks like art. It presents a juxtaposition of low and high, the ordinary made extraordinary, the transfiguration of the commonplace.

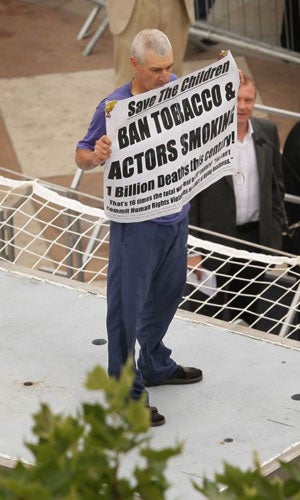

And then it starts, and the real live humans get involved, with both scheduled and unscheduled contributions. The concept in all its purity immediately collapses. Of course Antony Gormley’s One and Other had let itself for almost anything. Nobody could really complain when, through smart timing and inattention from security staff, the launch was convincingly hijacked.

It looked like somebody was doing some quick last minute repairs. How easily the man got himself helped up by a mate, via the safety net, onto to the plinth, to stand there, iron faced, with his placade promoting its strange cause – to ban actors from smoking - while the Mayor of London and the artist himself made their opening speeches, trying to sound as if they didn’t really mind about this piece of improvisation.

Gormley’s work has certainly been moving in this direction. For years he used exclusively his own body. The Angel of the North is nothing but a giant plane-winged version of himself. But recently he’s been recruiting models from the general public. The people of Tyneside, of Malmo in Sweden, of Menzies in Western Australia, have all been measured up and Gormed into crowds of standing effigies. Then there was the fog box at the Hayward Gallery, in which real living walking people became part of the show. And now volunteers – one person, one hour each, for a hundred days - make the show themselves.

Is it art? If it is, is the business of art critics to review it, as if it were (say) a continuous performance? What, treat these people as if they were all artworks or artists? All 2,400 of them? Well, frankly, why not? Other hand, who could be bother? And happily the very first two Plinthers seemed to show roughly the range of possibilities. Call them those who do, and those who don’t.

The cherry-picker approaches with the first one, a smiling woman in her thirties. Invited to “do the gentlemanly thing”, the iron faced man concedes, gets onto the lift and iis taken down. The woman takes her place, and we see her business at once. She’s doing it for charity. She stands with balloons and a lollipop sign, publicising the NSPCC Childline. More representatives of the charity are down on the ground, working Trafalgar Square.

Obviously it won’t always be charity. But you can easily imagine how many of the upcoming hundreds will be advertising something - a cause, a product, themselves, very often themselves. And you can imagine how these things might get tedious. (There’s a man in a panda costume waiting his turn.)

You can also imagine how they might go horribly wrong. (Surely someone with a powerful stride could actually run and leap over the safety net. Surely someone with concealed fuel and matches could… no don’t!) One way or another, these are those who do.

An hour passes. Ok, I went off for breakfast - and returned just in time to see the cherry picker make its second approach, and what should have been the first exchange of personnel. A man is now in place, shorts, red T-shirt. He has something printed on this T-Shirt, but it’s too far away to read. He’s taken a position quite near the front of the plinth. You wait. And you realise that something interesting is happening. Nothing is happening.

There he is. He looks like a perfectly friendly guy, but he isn’t up to any tricks. He’s just standing there. He’s being a proper living statue. He’s doing nothing in particular to draw attention to himself, except from being still and being on a plinth. He works perfectly.

A stationary occupant activates the power of this pedestal, this framing device. It demonstrates what happens when you take something, something without any inherent interest, and put it a focus on it. It has to be something pretty boring, or the effect won’t work - or at least it won’t show. But when you find that you’re looking at nothing special, or at nobody special, but gripped, you know you’re in the grip of a picture.

It made me think of something said by Pascal, the 17th century catholic puritan. “What vanity painting is, attracting admiration by its likeness to things of which we do not admire the originals.” He was pointing to how a picture, just by being an image, fixes our attention on things that otherwise we wouldn’t bother with. One and Other isn’t an image, but the plinth works in a similar way. It puts a frame on something of no real interest, and holds you looking.

It might take you back to the famous coffee-making machine, in the Computer Lab at Cambridge. At the start of the 1990’s the world’s first web-cam was turned upon it - simply so that people working in the building could find out if the pot was currently full. In the course of that decade, more and more people logged on from around the world to watch this utterly uninteresting spectacle. Such is the power of an image. And remember that One and Other is on web-cam too. You can watch it now. You can watch its weekly highlights too, with Clive Anderson.

Over the next hundred days, One and Other will probably turn out to be a whole lot of different things. It will be a freak-show of exhibitionism, an open-air Big Brother. It will be a public forum, a Speakers’ Corner, though rather hard to hear up there. It will be a kind of nice ID Card, a declaration of democratic citizenship. It will say that we’ve all got a soul, that we’re special, individual, unique.

You can go along with Mayor Johnson’s charming pun. “We may have lost the People’s Princess, but we’ve got the People’s Plinth.” You can put your faith in the vicar on Saturday’s Thought for the Day: “There is no such thing as an ordinary person. This pedestal will celebrate human extraordinariness in all its forms.” When they do the weekly highlights, they’ll surely go for any signs of extraordinariness. Alternatively, you can fear for the worst. What about the bits they just daren’t show again?

But the true message of One and Other, I believe, the one we should try and latch onto anyway, is the message of the Cambridge coffee pot. Stick with the low lights. If the Plinthers can only learn to be still, if they can just refrain for an hour from expressing themselves, they’ll have a power they never imagined. There is such a thing as absolute plain ordinariness. It can be absolutely fascinating.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments