The shady world of art auctions: How can a Picasso truly be worth $179 million when the art market is so murky?

Chandelier bids, guarantees and the duopoly of Christie's and Sotheby's — Matilda Battersby shines a light on the art auction process

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

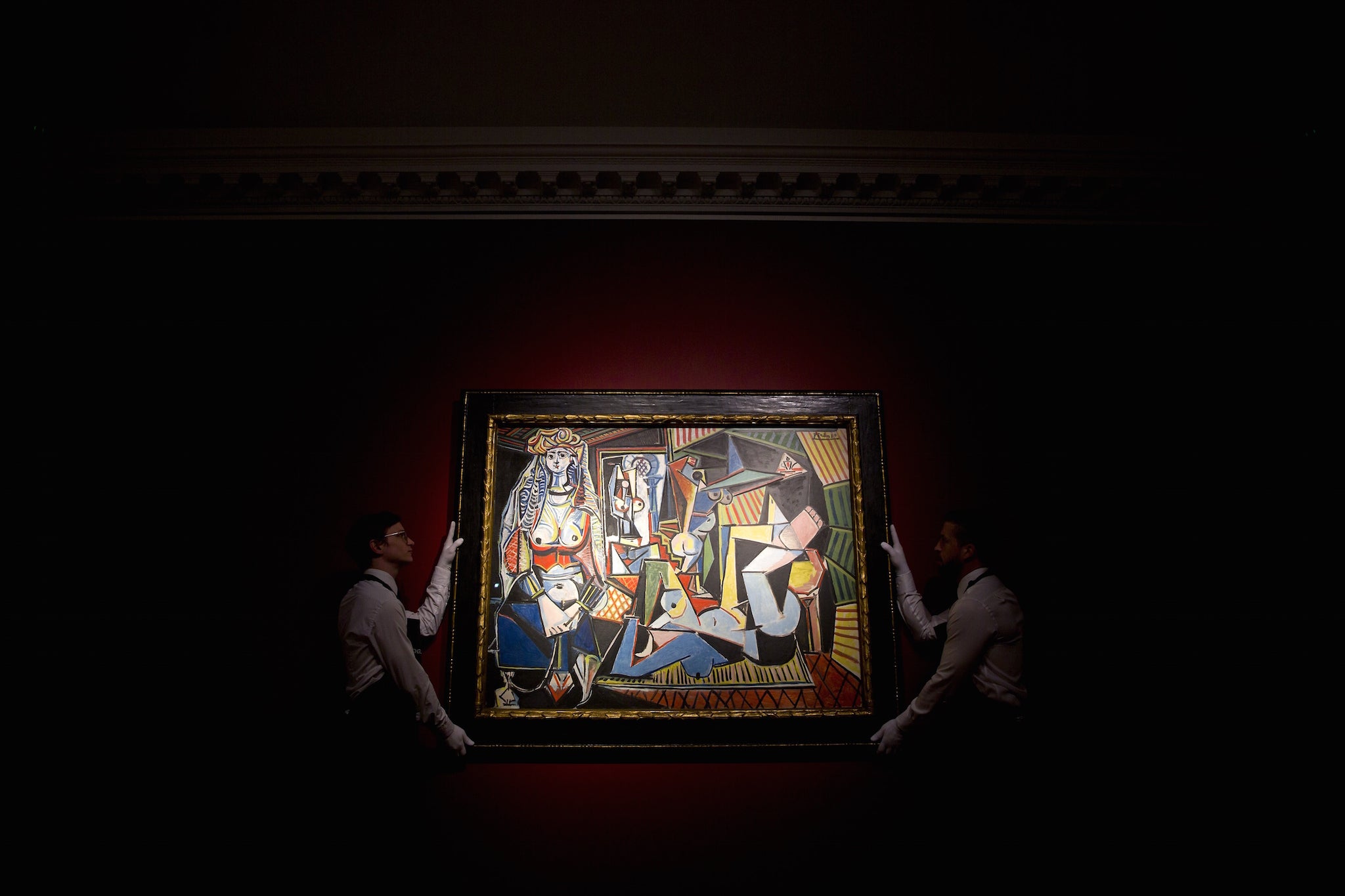

Your support makes all the difference.A Picasso masterpiece has become the world’s most expensive painting ever auctioned fetching $179 million at a Christie's sale overnight.

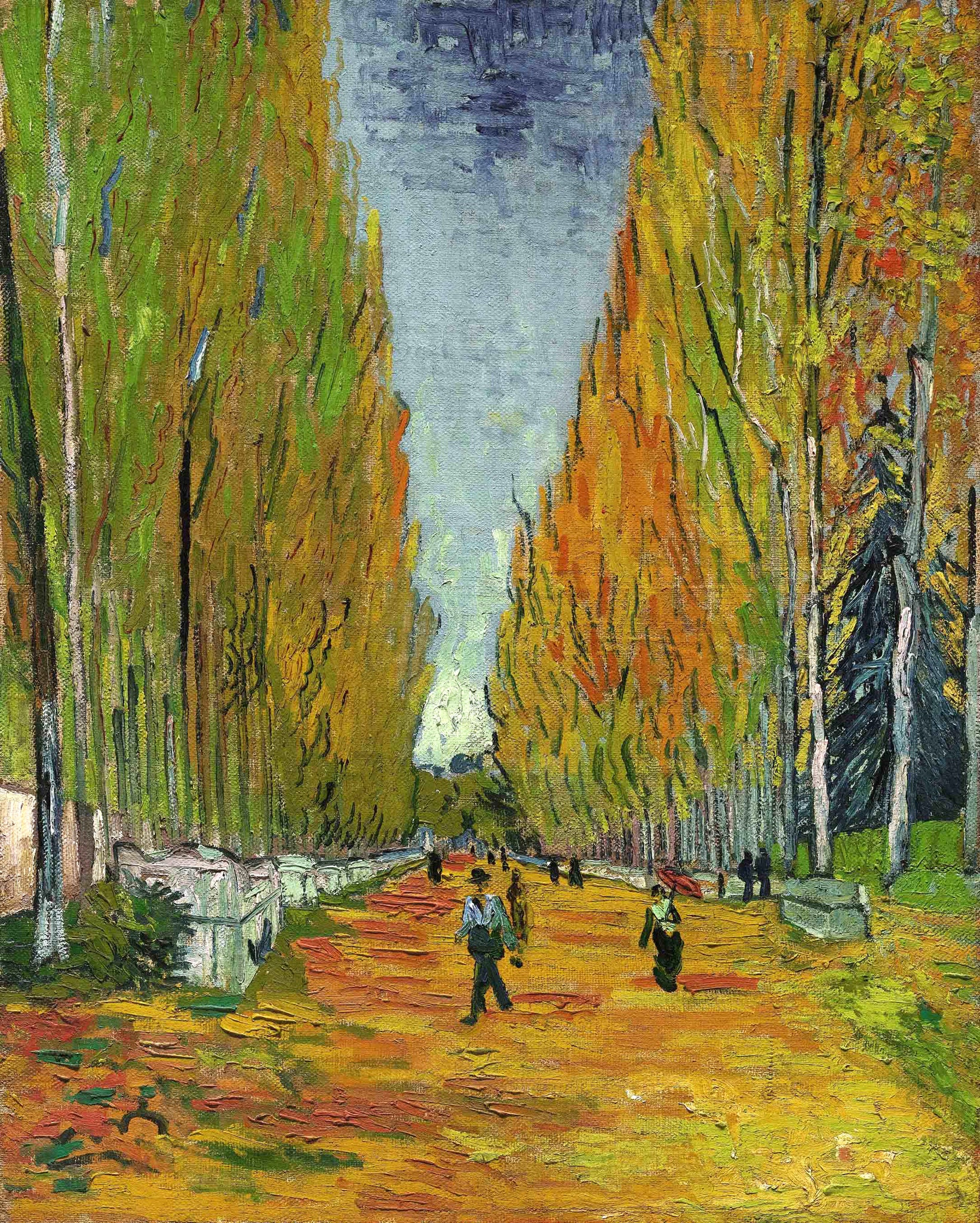

Granted the painting, Les femmes d’Alger (version O), is acknowledged to be one of the best pieces by the Spanish artist still in a private collection. But following last week’s blockbuster $368 million Sotheby’s sale, where pre-sale estimates were surpassed by tens of millions of dollars and a van Gogh sold for a record-breaking $66 million, is it any wonder analysts are eyeing the newly blown up art bubble with caution.

The art slump which followed that notorious September 2008 Sotheby’s auction when Damien Hirst works sold for an unprecedented £111 million on the very day Lehman Brothers collapsed, heralding the global financial crisis, seems barely to remain in the memory. The investors throwing more money than most of us will earn in a lifetime at artworks (which just last year were worth half that price) either believe their investments are safe or are so filthy rich they don’t care.

It is 19th and 20th century artists rather than YBAs that are commanding the highest prices in 2015. In February Paul Gauguin's When Will You Marry?, a stunning portrait of two Tahitian women, became the most expensive known single artwork to have been sold, bought privately by a Swiss collector for $300 million. Sales of the most-coveted painters - Cezanne, Matisse, Warhol, Rothko, Koons, Roy Lichtenstein and Lucian Freud — account for a massive chunk of the market annually. In 2013 a whopping 82 per cent of the money spent on art went on just 6 per cent of purchases.

At last week’s Sotheby’s spring sale the purchaser of Vincent van Gogh’s L’allée Des Alyscamps was identified by the waiting press only as a bloke speaking Chinese and wearing (unusually for the setting) a hoodie and jeans. A Japanese dealer sitting next to him claimed the buyer was speaking Mandarin but was not native Chinese. Beyond that, and bar the fact that he was the most impressive in a four-strong bidding war, we know nothing.

But, while the glittering auctions at Christie’s and Sotheby’s (and it is only those two places, really) command the eyes of the world the rest of the market is conducted under murkier settings, at least in terms of transparency. Quite for how much and by whom some of the most impressive pieces - and some of the lesser ones by big names — are being traded is anybody’s guess. But it is something of an open secret that auctions of works by major artists can be manipulated (mostly entirely legally, but manipulated nevertheless) to improve the values of works that are sold privately.

A Willem de Kooning collector, for example, might allow his finest example to be sold by Christie’s or Sotheby’s and watch smugly as a bidding war ensues. Once that piece has gone for an inflated value it follows that the remaining pieces in the collection will suddenly be worth more. Win win.

Equally the practise of guaranteeing an artwork (auction houses agree to buy work if it fails to sell) can provide opportunities for collectors. This is because an auction house is perfectly within its rights to minimise its own risk by allowing a third party to take on their guarantee. Sotheby’s revealed in April that of the $279 million guarantees it had made, $65 million were passed off onto third parties (probably a loaded high net worth collector) in exchange for a fee. Also, if a collector acts as guarantor of an artwork it can help to fix prices - it quite literally “guarantees” that it will sell at a minimum price and is yet another win win scenario: if the piece doesn’t sell for more, the collector gets a relative bargain; if it does sell, collector gets a nice fat fee.

More worrying than guaranteed bids is the shady, but again perfectly legal, practise of chandelier bidding - where the auctioneer pushes the price up by appearing to take an entirely fictitious bid. In the days when you had to be careful you didn’t nod or wink or scratch your head too visibly for fear of accidentally bidding mistakes might have been made. But with telephone bidders and huge competition you have to be rather bombastic to get a bid recognised nowadays - and an auctioneer would have to work pretty hard at making a chandelier bid look convincing.

Whoever these people are who are buying (and with the global art market worth $60 billion a year there are plenty of them) the concern is that with an effective duopoly of Christie’s and Sotheby’s controlling the market something has got to give at some point. Nobody is suggesting that a Picasso is a bad investment. Hell, there are plenty who’d argue its value would be maintained at any price simply for the privilege of hanging it on your wall. But as the auction-process spirals further into a game played by billionaires for the pleasure of winning one has to wonder where it’s going to end - and quite how it is going to impact other senses of the value of art. If today’s artists like Hirst expect to sell their work for millions - in contrast to van Gogh whose paintings might now fetch millions but who didn’t sell one in his lifetime — what on earth will they be worth in a hundred years’ time?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments