Tate Modern’s autumn show, The World Goes Pop, finally gives female pop artists their dues

A valuable corrective to the notion that Pop Art was a male preserve

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

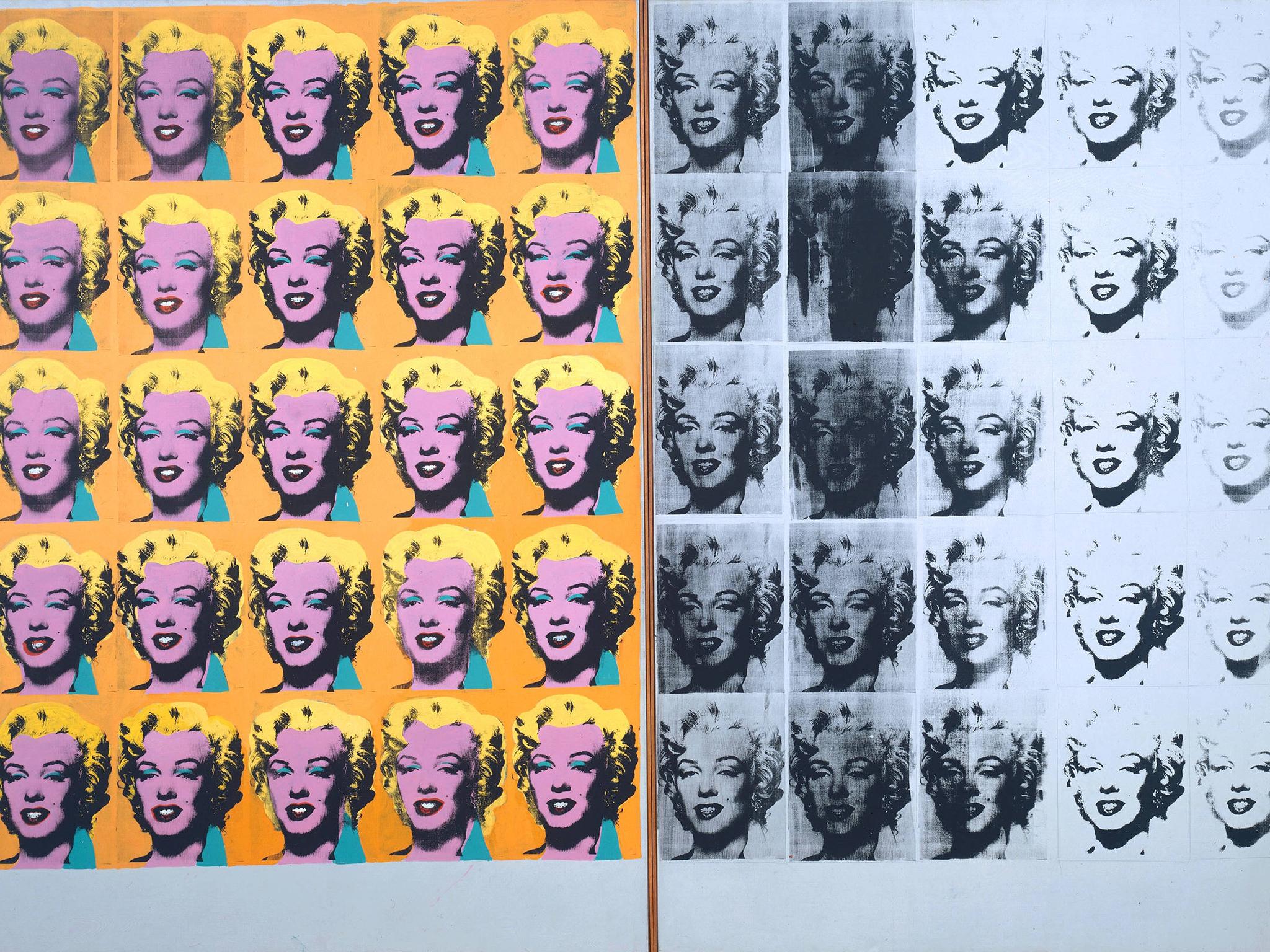

Your support makes all the difference.Marilyn Monroe’s face, printed over and over again. Cartoon-strip women, embraced by lovers or crying on the phone. Some of the most famous works of Pop Art certainly make use of the female image – but they were made by the big poster boys of the mid-20th century movement, Andy Warhol and Roy Lichtenstein. They formed a colourful contingent along with, er, other white, Western men – Peter Blake, Richard Hamilton, Robert Rauschenberg, James Rosenquist, David Hockney, Allen Jones. Because Pop Art had XY chromosomes, and only spawned in New York, LA and London, right?

That received notion is about to be, well, popped. The Tate Modern’s blockbuster autumn show, The World Goes Pop, offers a wide-ranging look at the movement from a global perspective, featuring the work of 65 lesser-known artists from Austria to Argentina, Japan to Iran. We think of Pop as predicated on the iconography of the American Dream, all advertising imagery and mass media, Coke bottles and soup cans – but the show will provide a glimpse of what Pop looked like in countries under Communist rule, or on continents that had yet to experience a consumerist boom. It turns out many of Pop’s signature elements – flat, bright colours; a debt to graphic design; satirical intent, and a playful approach to the star image – rippled right round the globe.

But the show doesn’t just offer an international perspective on Pop Art’s style and subversion – it also provides a valuable corrective to the notion that Pop Art was a male preserve. There are 25 female artists in the show, and many use and abuse Pop Art motifs to offer a coruscating feminist critique of the societal norms of the Sixties and Seventies.

“I think it’s great that they’re revisiting that period and looking at what other artists were doing – that whole Pop Art movement was really male dominated, in terms of who became visible,” says Judy Chicago, the 76-year-old American who is widely recognised as the grande dame of feminist art. “That’s the mainstream narrative: white male artists, with a few artists from other countries, a few artists of colour, a few women artists fitted in.” Like many others in the show, Chicago related to Pop Art aesthetics, but never considered herself part of the “scene”.

The Tate show features three of her spray-painted car bonnets, with boldly graphic, pastel-hued paintings of reproductive organs. The designs are based on a series of paintings that she did as a student at the University of California in Los Angeles in 1965, which were slammed by her (white, male) tutors. “They hated my colours, my imagery … I actually destroyed those paintings.” Much later, she found her old plans to turn the works into car “hoods”, and finally realised her youthful ambition in 2011, spray-lacquering her feminine designs over the symbolically masculine car bonnets.

But it seems even within the Pop scene there was some resistance to women – Chicago recalls meeting artist Marisol Escobar in a New York bar. One of the more high-profile female pop artists, she was pals with Warhol and Lichtenstein, and her witty sculptural work was shown by the influential gallerist Leo Castelli. “Marisol said to me, ‘the men hate me’ – sort of out of the blue!” confides Chicago. “There were a lot of important women, like Marisol, who were really not garnering the level of attention that they deserved – or that the men were getting.”

The Tate show will help put women back in the frame. And what those women put in their own frames was often art about being a woman, wresting female identity back from a culture where women were presented as either housewives or pin-ups. Contributing to the surge of second-wave feminism, they used Pop Art to reflect, critique and mock the prevailing stereotypes of the era.

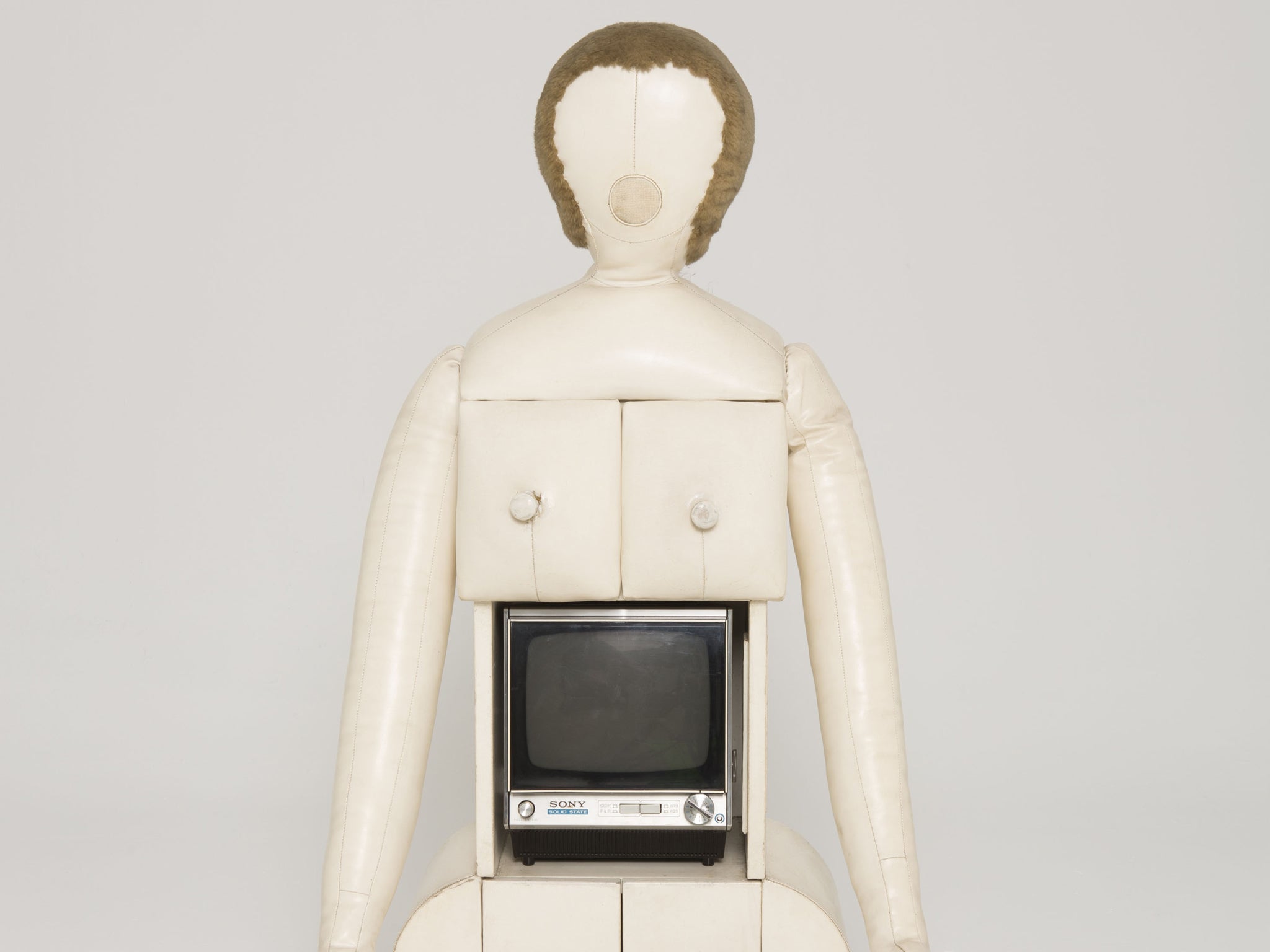

Chicago was not the only one to sharply clash feminine, romantic or bodily imagery with masculine forms and mediums. The show also features Austrian artist Kiki Kogelnik’s 1962 work Bombs in Love, featuring two bomb casings gaudily decorated with splayed legs and acrylic lovehearts; Belgian actress-turned-artist Evelyne Axell who put a scarlet-painted rubber tyre over her blocky painting of naked women about to kiss in Erotomobile 1966, and France’s Nicola L’s body-shaped TV cabinet, which literally objectifies woman, reducing her to a source of entertainment in the domestic sphere.

Meanwhile, New Yorker Martha Rosler’s series, Body Beautiful, or Beauty Knows No Pain (1965-72), splices kitchen appliances – housewives’ friends! – with hyper-sexualised, mass-produced images of women’s bodies: a washing machine covered with a bare bum, or an oven with a perky tit on the door, glaringly uniting the contrasting, yet equally limiting, expectations of women as simply domestic or sexual beings.

And Rosler goes yet further, turning her critique inwards on Pop Art itself: Woman with Vacuum, or Vacuuming Pop Art is a collage of a blandly smiling woman vacuuming a corridor – lined by works by male pop artists. It may not be subtle, but it makes a salient point about women’s place in the home – and in the artistic movement. Similarly, Natalia LL’s Consumer Art films (1972-5) show models suggestively eating bananas and sausages. Although comic, the title and performance come together to ask troubling questions about how we expect to be able to “consume” the female body, not least in the art world itself, the Polish artist finding correlatives between Pop Art’s visual obsession with consumables, and its attitude toward female artists.

Parisian artist Dorothee Selz further explores notions of consumption through her choice of materials: she’s long used food to create edible works. The Tate will show her 1973 work Relative Mimetism, pairs of photographic self-portraits in which she emulates the faintly absurd poses of pin-up girls. The sugary, consumable nature of these images is highlighted by framing both photos with whirls of bright icing.

“At this time I was interested by the feminist movement – and still am – so as a visual artist I was very much touched by the cliché of ‘the woman’ in every advert,” says Selz. “The pictures I made reflect, with a kind of humour, on the role of the woman, which was mostly to be the mother or the seductive woman. I thought it was interesting to use very popular images of advertising to speak about that, as a kind of denunciation.”

Selz suggests that, depressingly, the works are just as relevant today. “At the time, I thought society would develop in a positive way and that this [way of representing women] would probably disappear – I was very naive! And very idealistic. But today, it would be possible to do exactly the same work.”

She’s right, of course. While Western women at least may feel less trapped by the domestic sphere or housewife ideals in 2015, the female body as commodified sex object has hardly evolved; be it airbrushed adverts or eye-wateringly explicit YouTube videos, women’s flesh is still very much on the consumerist frontline. Perfect timing, then, to rediscover the women who used Pop Art as a way to take a pop at such limited, and limiting, representation of femininity.

‘The World Goes Pop’ is at Tate Modern, 17 Sept to 24 Jan, tate.org.uk

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments