Rothko: Art on stage

As a new play about Mark Rothko opens tonight in the West End, Paul Taylor looks at how great artists and their work can be vividly brought to life on stage

These days, nobody looks askance if a high-end artist is also the owner of a fashionable restaurant. Think Damien Hirst and Pharmacy – his erstwhile Notting Hill trough for the trendy. It was adorned by the artist's own pill paintings and fell foul of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society which averred that the pill bottles and items on display (to say nothing of the signage) could cause confusion in the public's mind with a genuine chemist. So there we have it: bafflement outside as to what the place is and inside where it was the difference between real and genuine art that fooled many.

A far cry, all told, from the late 1950s – the period in which John Logan (Oscar-nominated for this screenplay of Gladiator) has set Red, his stage drama about the American Abstract Expressionist painter Mark Rothko, which opens tonight at the Donmar Warehouse in a production directed by Michael Grandage. The art world reeled when this ostensibly least worldly of artists – who suspended his spiritual signature repeatedly in his floating colour-field paintings – accepted a commission to produce a set of murals that would decorate the swanky Four Seasons restaurant in New York's latest iconic temple to Mammon, the Seagram Building.

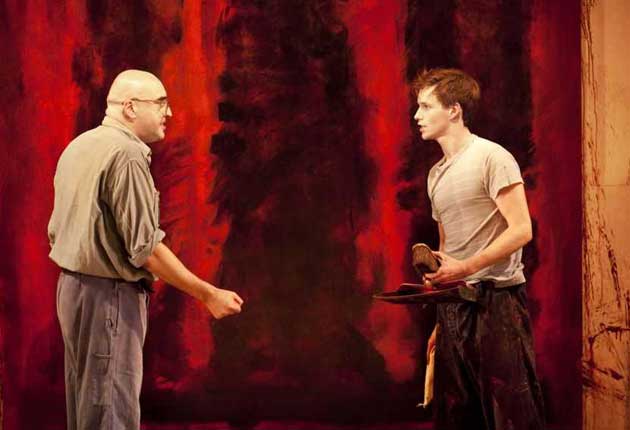

Red has been left pretty much under wraps so that it can surprise us tonight. We do know, though, that it will be partly concerned with generational succession in the relay-race of creativity – Alfred Molina plays Rothko; the extraordinary Eddie Redmayne portrays the composite assistant-figure whose talent is edging towards Pop Art. We can suspect, too, that the play may pinpoint the compromising Seagram commission as the start of the personal unravelling that led to Rothko's suicide in 1970. London is, in fact, the beneficiary of the artist's decision to renege on the Four Seasons deal and retain the paintings he had created in furtherance of the project. He donated nine of these painting to the Tate where (though now temporarily on display at Tate Liverpool) they are to be found in a dimly lit chapel-like space at Tate Modern.

It will be interesting to see what degree of physical presence the play gives to these pictures. There is a whole sub-genre of drama that has artworks at the centre – whether in stage pieces, or in film. The mobility of the camera permits a subjective scrutiny denied to theatrical presentation – which has its corresponding advantages, not least the sort of animal immediacy of the work being on stage. On stage, too, you can artfully keep secret the look of the art and the ability to keep a picture's back turned to an audience can be made into a virtue, as when Howard Barker's Scenes from an Execution (which starred Glenda Jackson as a 16th-century female Venetian artist ) dramatised how the state effectively neutralised a subversive oil painting (a non-celebratory depiction of the Battle of Lepanto) by turning it into a media event. We watched as droves of gallery-goers stared up at the picture and the focus was on the ideologically manipulated reaction. A mutilated survivor of the actual battle managed to scrounge a few lire each day by turning himself into a sort of fairground circus attraction.

Alternatively, it's open to a dramatist and director to flood the stage or the proceedings with a picture. In the first act of the Sondheim musical Sunday in the Park with George, Seurat's painting Un dimanche après-midi à l'Île de la Grande Jatte is recreated in three dimensions on stage. Its constituent elements – human figures and pointillist cut-outs of animals and trees are shown being regrouped in various provisional arrangements at the whim of the artist, until the whole is finally consummated at the magical close of the first half with the freeze-framing of a running figure, who has only made it into immortality in the nick of time. Or, more subtly and profoundly, there was Neil Bartlett's highly original 1997 devised piece, The Seven Sacraments of Nicolas Poussin, which evoked and gave added depth of meaning to the suite of paintings hung in the National Gallery of Scotland. These oils depict the religious ceremonies designed to commemorate and care for the rites of passage of the human body from birth to death. Bartlett highlighted our increasingly awkward relationship to the sacredness of such key moments in a secular age by positioning himself as a gay man in relation to the pictures. The show (which later went on to become an oratorio) was originally set in the Royal London Hospital, with Bartlett posing at the start as a medical lecturer. The paintings were evoked by their details. The autobiographical protagonist tended to identify with the figure in black who hovers on the edge of many of the pictures and for the final vignette of Extreme Unction, the audience were moved into another lecture theatre to see Bartlett sitting beside an empty hospital bed, completely still, his hand stretched out like the man in the painting in an unforgettable and immemorial image of loss, grief, and loving support. Never have pre-existing pictures been more immanent or of more moment in a theatre piece.

Some plays are acute in picking up on the physical condition, the debatable authenticity, and the iconography of an art work as a way of pursuing their thematic preoccupations. Take Alan Bennett's wonderfully clever and illuminating A Question of Attribution which has, at its centre, Anthony Blunt, the Keeper of the Queen's Pictures later exposed as a spy. The slides in which a fourth and fifth man are uncovered by X-ray in the Triple Portrait, allegedly by Titian, find their mischievous parallel in the slides shown to Blunt by his MI5 interrogator. By implication, both investigations are judged to be never-ending, arid exercises which strive unavailingly to reduce the enigma of art and human mystery to the status of riddles that can be solved.

David Edgar's 1994 play Pentecost combines a penetrating sense of what visual iconography can betoken culturally with a strongly theatrical instinct for how the physical state of a picture can make an impact onstage. With a convincing design by Robert Jones in the first RSC production, the play is set in an abandoned church in an East European country to whose repeated experience of invasion (Mongol, Turkish, Napoleonic, Nazi) and 40 years of communist failure, the building bears material witness (the scratching on the wall of torture victims; a heroic daub of the revolutionary masses). But such memorabilia would fade into insignificance if, as looks likely, the remains were discovered here of a fresco that could either be a Giotto or the work of an earlier genius who had anticipated his use of perspective and ability to depict individualised human emotion by a century.

As a device for highlighting the intricate internal tensions and confusions about values in post-communist countries, the fresco is brilliantly successful. What's interesting here, however, is how cleverly Edgar uses the iconography of the picture to pursue his themes. For a start, the art work, though fictional, can be shown to us, since it is, essentially, Giotto's Lamentation Over Christ with certain key details significantly altered. Aptly, in a play named Pentecost, the riddle of these differences turns out to be a linguistic one, the painting possibly the work of an itinerant Arab whose St John gestures differently because he was bringing Islamic cultural assumptions to the table. The opening-up of frontiers and the multilingual diaspora are tragically exemplified by the group of refugees who take the art work hostage.

How much does it hurt a play such as Pentecost that it is, from the best possible intentions, not founded upon a real but a fabricated painting? Certainly, it prevents David Edgar from fulfilling one of the main criteria of this type of drama – that it should make one want to rush off to the appropriate gallery or space and drink in the picture anew. Film can have a fluid relation to art works, thanks to the camera. But I have, to my recollection, only once been to a theatrical show where the audience were moved in relation to the action in more ways than one. This was in the otherwise fascinating Big Picnic, a huge show about the fighting of a Scots brigade in the trenches in the First World War and premiered in an old shipyard in Govan. The banks of bleachers were whisked en masse further and further down the line to death. Alas, the result was like being in a golf buggy and being transported from one very different kind of "hole" to another. Red will have done a part of its job well if it sends people flying to the Tate, where, of course, you can move around at will or enter into the stillness of concentration that these theatre pieces promote.

Red, Donmar Warehouse, London WC2 (020 7240 4882) to 6 February

In the frame: Art on stage

Art

A white-on-white (and Emperor's New Clothes?) painting becomes the bone of contention between three Parisian chums in Yasmina Reza's artful piece (above) about the nature of male friendship.

The Giant

Antony Sher's play focuses on the carving of Michelangelo's nude statue of David, with Michelangelo and his rival Leonardo da Vinci losing their respective marbles over Vito, the (fictional) model whose curly-mopped beauty inspires hands-on creativity.

Vincent in Brixton

By the end of Nicholas Wright's profound play, the young Van Gogh is roughing out the famous sketch of his boots and on the brink of becoming a real artist, having served a psychological apprenticeship as the lover of his similarly depressive older landlady, brilliantly played in the original by Clare Higgins (below).

The Line

Timberlake Wertenbaker's new play about the artist Suzanne Valadon's brush with Edgar Degas has become a talking point because the playwright accused negative critics of being too tired and emotional, after an awards lunch, to judge it properly.

Six Degrees of Separation

A Kandinsky sheds a degree of mysticism on this otherwise worldly John Guare play about what happens to a well-heeled Manhattan family when it is infiltrated by a young fraud who claims to be the son of Sidney Poitier.

Have your say

What was the most memorable arts event of 2009? Were you blown away by 'Enron' at the Royal Court? Did you love Lily Allen at Glastonbury? Was Antony Gormley's Fourth Plinth the defining cultural moment of the year? Or perhaps an unheralded gig or play in your local theatre stole the show?

Visit www.independent.co.uk/bestof09 or email arts@independent.co.uk to nominate your favourite in film, music, theatre, comedy, dance or visual arts with a brief explanation as to why it tops your list and we'll print a selection in The Independent Readers' Review of 2009.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments