Richard Hamilton: The most influential artist of his generation?

Three new shows dedicated to the playful and provocative work of Richard Hamilton mark him out as the most influential artist of his generation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Posthumous retrospectives are a tricky business. On the one hand, they lack the warm glow that comes with exhibitions of living artists at the end of their career. On the other side, they tend to come too soon for their work to be seen in the proper perspective of time.

One fervently wishes that this doesn’t happen to Richard Hamilton, who died in 2011. For he was a true giant of the postwar, arguably the most influential British artist of his time and certainly one of the finest. If any artist needs a comprehensive survey of his work, it is Hamilton, pioneer of Pop, political agitator, champion of Duchamp and Dadaism, the great artistic technician of the camera and the computer.

The art establishment has certainly gathered its forces to give him his due. The ICA, with which he was long associated, has an exhibition of two of his early installations. Tate Modern is holding a comprehensive retrospective, including more than 100 works. And the Alan Cristea Gallery in London is giving a showing to his prints, of which he became a master.

It could be almost too much of a good thing. Not with Hamilton. He had such an inventive mind that, however many works you see, it is always fascinating to follow where he takes you. As with Degas and Picasso, he is for ever searching for something as he picks up his pencil to plan out a work. That thing was a means of representing the modern world in all its technological and consumer brightness, whether it was consumer products, the imagery of personality or the wonders of the digital age.

It’s little wonder that he had such a technological bent. Born in 1922, he’d served as a jig and tool draughtsman (a reserved occupation) during the war and was called up into the Royal Engineers after the war, having been expelled from the Royal Academy Schools then headed by the anti-Modernist, Alfred Munnings.

If he didn’t take to his late call-up, still less to Alfred Munnings, his early art is full of that post-war spirit of new possibilities and new order. Modern design, modern art and modern living were in the air and as a designer and draughtsman he was completely at home with them.

If you are interested in Hamilton’s influences and his bent of mind then you may well be best starting with the ICA’s show of his two installations, Man, Machine and Motion from 1955 and an Exhibit from 1957. The former is a walk through series of blown-up photographs and engravings illustrating the themes of man’s progress in mastering air, sea and land.

The pictures are held precisely in frames of 4x8ft, above your head as well as either side and before you. They display not just Hamilton’s fascination with the mechanical and his concern with precise spatial plotting but also his humour at some of the old engravings of attempted flight (and abduction) and early car drivers with their florid moustaches and goggled outfits.

The second installation is on exactly the same grid pattern only Victor Pasmore at the ICA and the artist Lawrence Alloway had persuaded him to try the whole thing again, this time with abstract sheets of acrylic colour. The idea was to make an exhibition in which the viewer creates his own perspectives as he moves about. Even today, half a century later, it looks entirely modern and intriguing.

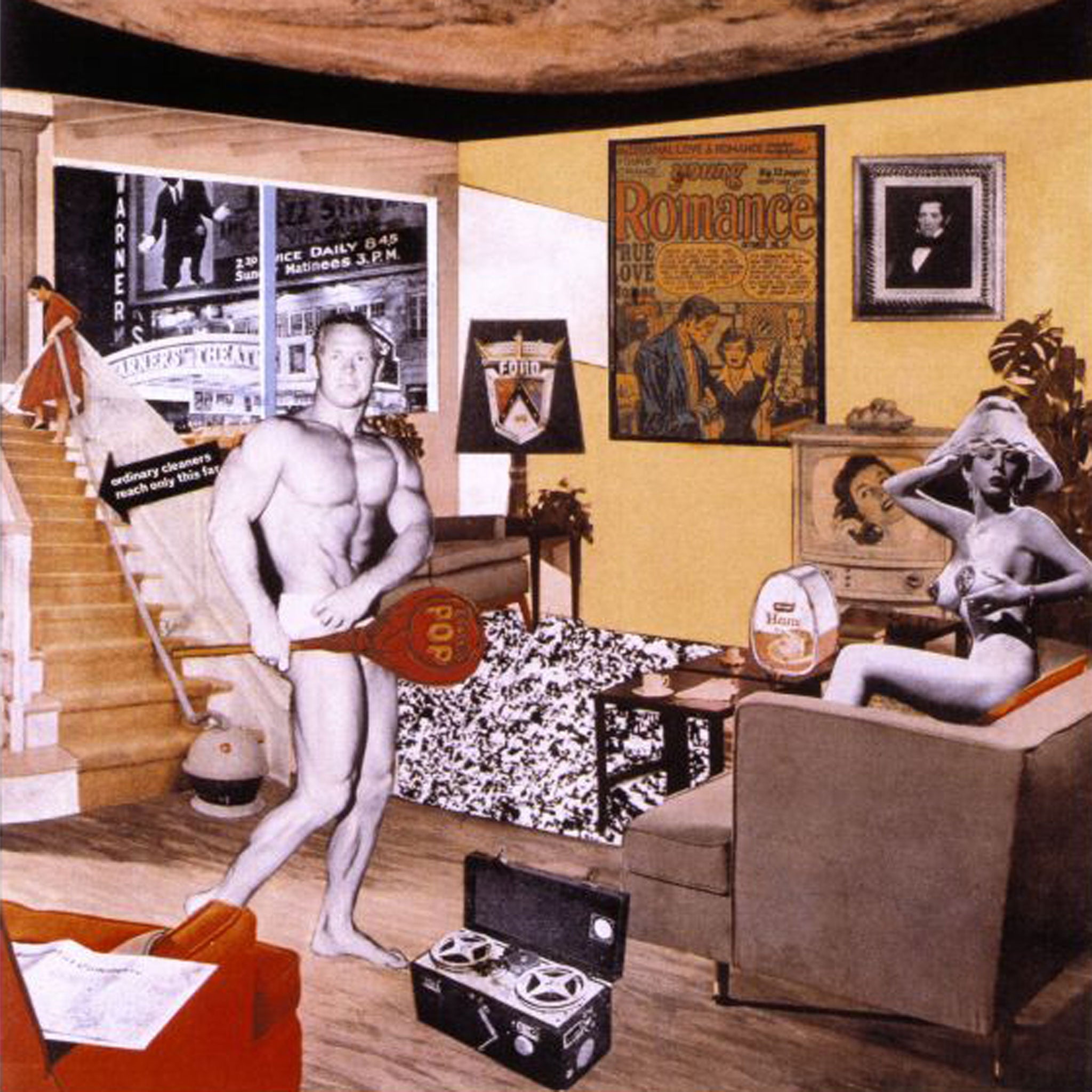

At the same time as he was doing this he was also combining the advertisements and pictures of the modern world in the first collages of Pop art. Tate Modern has, of course, the 1956 picture, Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?, which set it all off. They have also reconstructed the installation, This Is Tomorrow, Group 2, known at the time as The Fun House, which he made for the Whitechapel exhibition in the same year with John McHale and John Voelcker. It has lost none of its dazzle as the jukebox plays hits from the period and the fragmented walls are covered with pictures and videos from Hollywood and consumer products.

He followed this with a series of pictures in which he took elements of the metallic icons of the age, the Chrysler car and the German toaster, and combined them with paint and collage to give the sensation of modern life rather than just a representation of it.

Compare the endlessly inventive series, Hommage à Chrysler Corp from 1957 and Towards a definitive statement on the coming trends in menswear and accessories, a title taken from Playboy magazine, from 1962, with the pictures of his fellow Pop artists of the time and he instantly stands out for his sense of space and concentration. Far more concerned with perspective and less with colour, his paintings keep you at an ironic distance from the object, both admiring but critical.

Not that Hamilton couldn’t be direct when he wanted. His image of Mick Jagger and the gallery owner, Robert Fraser, shielding their faces from the cameras as they are driven off in handcuffs accused of drug offences is justly famous. It combines perfectly the blurred effect of the snatched shot with the sense of a moment. His trilogy of diptychs of painted pictures of a “dirty protester”, the military and the Orange Order in Northern Ireland are brittle, brilliant comments on the Troubles there.

When it came to the individuals he held responsible for the decline in society he saw in Britain when the utopian dreams of the immediate postwar evaporated in the society of “never had it so good”, Hamilton went for the jugular. Portrait of Hugh Gaitskell as a Famous Monster of Filmland, painted in 1964 after Gaitskell had disowned the anti-nuclear campaign, is brutal in its recomposition of a face as inhuman uncaring.

The installation, Treatment Room, of Margaret Thatcher lecturing wordlessly over a crumpled institutional hospital bed is horrific in its soundlessness. His portrayal of a grinning, idiot Tony Blair as a cowboy, Shock and Awe, from 2010, is merciless in its portrayal of the posturing of a would-be war leader.

They are all there in the Tate show, if a little diffused by being made merely part of the chronology. Where the Tate show is at its best is in showing Hamilton’s constant probing of the possibilities of technology in art. It starts with the drawings of reapers he made in 1949, continues with the abstract and near abstract pictures he made of trees and objects that whizzed by on his train journeys to teach in Newcastle in the early 1950s, takes in the extraordinary series of magnifications of a photograph of beaches and bathers, the reverse colour image of Bing Crosby, I’m dreaming of a White Christmas, and his homage to Marilyn Monroe, My Marilyn, in the mid-Sixties, and his spatial study of interiors which he developed from the early Sixties to his digital screenprints of the Nineties.

Through it all is his draughtsman’s eye, calculating what could be done with visual technology. A rare British champion of Dadaism, he spent a year re-creating Marcel Duchamp’s The Bride Stripped Bare by her Bachelors Even (The Large Glass). When Lichtenstein used a Polaroid camera to photograph him on a visit to New York he developed the idea to produce two volumes of pictures of himself taken by visitors to his studio in an exercise to show how even the simplest shot was shaped by the eye which took it.

In his final pictures, made just before his death and shown at the National Gallery just after it, and named after Balzac’s novella The Unknown Masterpiece, he pictures three great artists of the past, Titian, Poussin and Courbet, looking on at a digitally enhanced photograph of a nude. The portraits of the painters are painterly but it is the realistic figure of the woman which is most artificial. It was his final statement on the picture and perception.

A great artist, although I fear it may yet take another generation before his contribution to art is fully appreciated.

Richard Hamilton, Tate Modern, London SE1 (020 7887 8888) to 26 May; ICA, London SW1 (020 7930 3647) to 6 April; Word and Image, Prints 1963-2007, Alan Cristea Gallery, London W1 (020 7439 1866 ) to 22 March

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments