Return of the Mac: How a disastrous fire put architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh back in the limelight

The new Mackintosh Architecture exhibition at Riba in London will capture the full spectrum of his artistry, including his stunning ink drawings

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

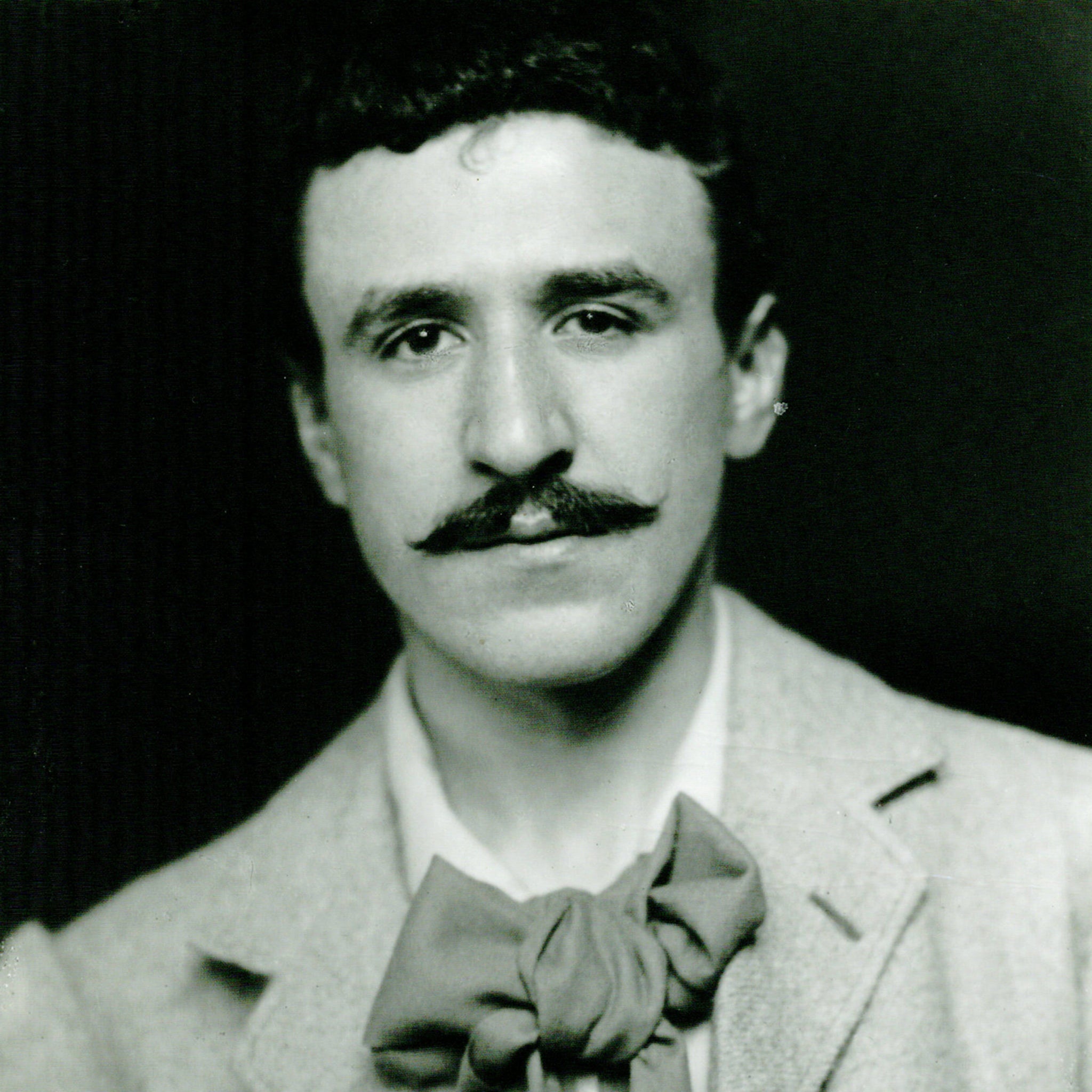

Your support makes all the difference.In the most famous photograph we have of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, the Glaswegian’s eyes burn softly and sadly; his face seems touched by melancholy like Droopy the cartoon dog. Yet the architect and artist’s ruffled tie and insouciant pose say something different – they say: “I am a creator, a modern man.”

A copy of James Craig Annan’s 1893 shot from the National Portrait Gallery sits at the heart of the Royal Institution of British Architects’ new Mackintosh retrospective, and it’s a picture you won’t easily forget. It speaks of missteps, underachievement, and a talent that wasn’t recognised until a century later – a recognition that has only grown in the wake of the fire last year that devastated one his most famous projects, the Glasgow School of Art.

It’s an artist’s lot to be mistrusted, maligned even. Mack felt the full force of staid opposition. Born in 1868, he had an incredible way with a pencil. But he was determined to codify a new architecture, one built on sensuousness, nature, light and space. He wanted to make something different from what was around – cloying Victoriana, overblown bombast. He wanted elegance: white walls, geometric squares.

Mac started as a draughtsman at local firm Honeyman & Keppie in 1899 and became a trained architect, then partner. His first major structure was the Glasgow Herald Building, finished in 1895, and over the next 20 years he completed only a handful of major building projects, including the School of Art, his most-well known then and now, which opened in 1909 after 12 years of construction. However, this new exhibition will capture the full spectrum of his artistry, including his stunning ink drawings and watercolours, and models of some of his interior designs for projects such as 78 Derngate in Northampton, a house he did up inside and out for the toy magnate Wenman Joseph Bassett-Lowke.

78 Derngate was his last completed building. His innovative style hardly appreciated, the commissions dried up, and in 1914, he quit architecture and moved disconsolately to Suffolk where he would pace the beaches alone, while prying locals accused him of being a German spy – a period caught by Emma Freud in her latest novel Mr Mac & Me. Then, in 1923, he moved to southern France to paint watercolours, before finally ending up in London in 1927 – where his tongue was cut out in an attempt to save him from the cancer that killed him the following year. He died with just £68 to his name.

He never built a house for himself, but instead, as with Derngate, transformed an existing Glasgow West End terrace with fresh new interiors. That house was, incredibly, bulldozed – but its interiors were recreated in the 1970s next to the Hunterian Museum & Gallery in Glasgow’s West End. The copycat version is encased in a concrete chrysalis, a fake house with a fake door which stops you in your tracks. It works perfectly because Brutalism is another futuristic, fantastic style that’s being very slowly appreciated after decades of being lambasted.

Inside The Mackintosh House I meet the Hunterian’s Pamela Robertson, who draws my eye to the “fall of the light” from the windows and the “restrained sculptural geometry” of the Art Nouveau furniture Mackintosh and his wife, Margaret, worked on together. The first-floor library is a particular surprise: a minimalist confection that’s airy, bright, white, and utterly at odds with stuffy Victoriana. The interplay of the quiet, subtle interiors and the building’s swaggering exterior brings to mind the jarring juxtapositions of quiet and loud in the songs of local post-rock legends Mogwai.

Mackintosh was private and never really tasted fame, and thus Robertson admits that “we know very little about him,” but nevertheless leads me to the Hunterian’s Mackintosh Architecture exhibition, which contains many elements of the London version of the retrospective that opens next week. Robertson explains the exhibition is based on her research project, which “provided the first overall view of Mackintosh’s architecture”.

Many of his designs – for a London theatre and Liverpool cathedral, for example – never made it past the drawing board: those drawings are here though – carefully detailed, full of natural shapes as if the architecture had sprouted from the ground. He was also less of a self-promoter than architect peers such as Frank Lloyd Wright, who, says Robertson, “was a lot more driven”. Though when we look back at Mack now as a posthumous star, it is important not to forget how integral his artist wife Margaret was to his work, contributing much to the interior design of his projects. Nor to neglect the fact that Mack was only one of a generation of Glasgow architects: less remembered is his equally gifted contemporary James Salmon, who built The Hatrack and Lion’s Chambers in Glasgow, both Art Nouveau classics.

While Riba’s exhibition will give a good measure of Mack’s work, his real masterpiece will remain on the windswept prow of a Glasgow hill. The turn-of-the-century School of Art mixes brusque façades with jaunty details such as fake dovecotes to splendid effect: when the western half of it burned down in May 2014, the outpouring of sadness was remarkable. “I first heard of the fire within hours of it starting via a text; people across the country were alerting friends about it almost immediately,” remembers Suzie Pugh, curator of Riba drawings and archives at the V&A and co-curator of the exhibition with Robertson. Today, beeping builders’ lorries reverse up and stone is off-loaded. “Hopefully the building can be restored to its former glory,” says Pugh.

As for the man behind the edifices, he still remains a mystery. Suzie Pugh laughs over a rare tale which brings him to life: “One of my favourite stories about Mackintosh involves him jumping into a pond dressed as Father Christmas. He and Margaret never had children, but he dressed up in a costume to entertain the children of his friend and patron, William Davidson. He got too close to a naked candle on the Christmas tree and the cotton wool of his costume went up in flames, forcing him to jump in the water to extinguish himself!”

Little did Mack know then that another fire long after his death – the one at Glasgow School of Art last year – would finally put him in the limelight.

‘Mackintosh Architecture’ is at Riba in London from Wednesday to 23 May

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments